Why Do Foods Make Us Gain Weight and Where Do Food Cravings Come From?

Exploring The Forgotten Side of Weight Loss

Fundamentally, I believe that the existing notion that weight is simply a product of how many calories you consume and how many you expend is not correct (although I will also admit I know a few people who have lost significant weight just by following a prolonged calorie restriction diet). Instead, various factors play a pivotal role in whether a calorie will or will not become fat.

Some approaches for addressing this puzzle (such as the one I successfully utilized recently) have existed for a long time, while others are fairly new.

In the first part of this series, I discussed the dietary conundrum our society faces, shared my thoughts on some of the common diets, and explored the ever-present problem of food cravings.

Thoughts on Diet, Food Cravings and Weightloss

Although I have spent a great deal of time studying the field of nutrition, I have been hesitant to write about it. This is because opinions on the subject differ so much that regardless of the position you put forward, people who feel strongly on the issue will appear and put forward evidence challenging and refuting whatever you suggested. This is …

In this article, I will attempt to:

•Answer the complex question of why the same food causes different individuals to gain different amounts of weight.

•The best approaches we have found for addressing food cravings

•My approaches for weight loss (which became necessary for me to evaluate since all the time I’ve spent on Substack caused me to gain a lot of weight), which allowed me to lose 31 pounds in 30 days.

Why We Store Fat

Since middle school, I have believed the nutritional dogma that all calories are equivalent is wrong and instead thought that the types of calories (e.g., those from processed grains versus those from fats and meats) are the primary determinant of if you gain weight. Thus, I tried to avoid excessively processed foods, never gained weight, and assumed for those who did, it was entirely due to their choice to eat those processed foods.

However, in my mid-thirties, this perspective changed because I noticed that if I ate what I had previously been able to eat (while staying skinny), I would instead put on weight. I thus had to begin becoming much more mindful of what I ate to avoid gaining weight. Going through this made me realize that there was something else in the picture which was fundamentally changing how we metabolized the food we ate, so I began looking into many different explanations for what that factor might be.

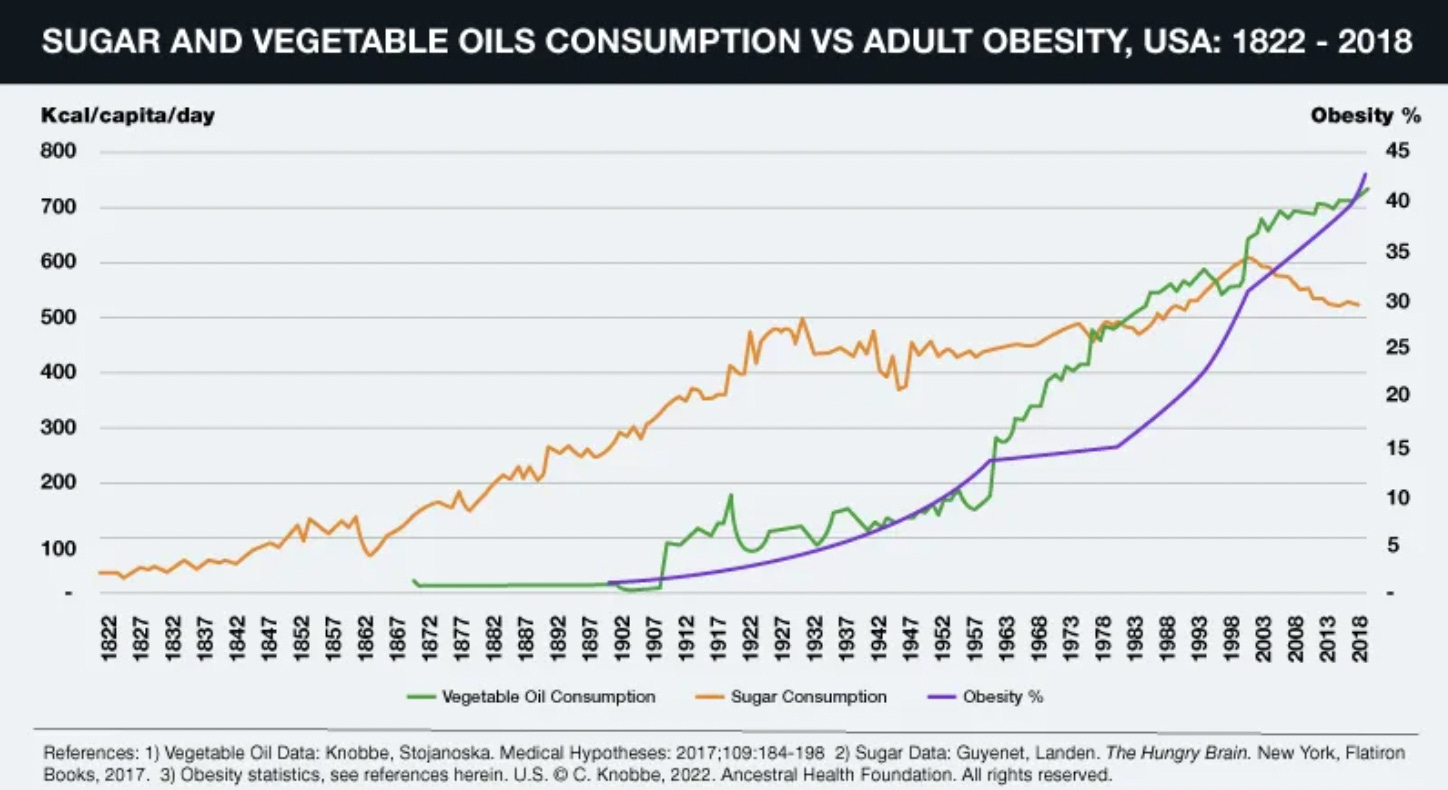

This question is surprisingly difficult to answer because so many different variables are at work. For example, consider this comparison between high fructose corn syrup consumption (which I believe causes obesity) and obesity rates in the United States. Depending on how you look at this graph, one could argue the two are, or are not, related.

Note: the graphs I have looked at assessing this correlation vary somewhat. This is one of the more commonly used ones (which is typically used to argue increasing high fructose corn syrup consumption is not the cause of the obesity epidemic).

Other correlations are a bit more precise. For example, Dr. Mercola has argued that seed oils (due to their high omega-6 content) contribute to obesity because their presence in the mitochondrial membrane impairs mitochondrial respiration (which is necessary to burn up the calories we consume).

I will now look at some of the strongest explanations I have seen put forward to explain why certain bodies tend to gain fat.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and EMFs

Individuals have radically different susceptibilities to toxins, including electromagnetic fields (EMFs). Arthur Fristenberg, one of the more EMF-sensitive individuals, has written one of the best exposés on this subject, The Invisible Rainbow. One of the ideas he put forward is that increasing EMF exposure is responsible for the widespread diabetes and obesity epidemic in our society. In addition to citing potential correlations to prove his point, he also provides a mechanism with some supporting evidence.

Fristenberg argues that diabetes results from the mitochondria being unable to metabolize (burn) all the fuel they receive, so it instead ends up as fat. The supporting pieces of evidence he assembled were:

•Researchers found that the oxidative capacity of the muscles was a better indicator of insulin resistance than their fat content.

•A 2014 study studied a group of women with insulin resistance that were not yet diabetic. The only two physiologic abnormalities they could detect were their oxygen consumption during exercise was reduced, and mitochondrial respiration in their muscle cells was reduced, both of which implied mitochondrial dysfunction was the cause of their insulin resistance.

Note: one of the most intriguing tests I have found for assessing the overall health of a patient was developed by Frank Schallenberger (a leading expert in ozone therapy). It measures how much oxygen a patient inhales is converted to carbon dioxide, which serves as a surrogate for mitochondrial function.

•Placing diabetics on calorie restriction and requiring them to exercise increased everything cells needed to burn calories (e.g., the total number of mitochondria and the activity of the enzymes in the Krebs cycle, which mitochondria use to burn fat) except the final stage of the process, the electron transport chain (which is where oxygen essentially "burns" fat). Fristenberg's model argues that EMFs impair the electron transport chain.

•A 2010 review that assessed the existing research on the role of mitochondria in diabetes concluded that due to "failure of mitochondria to adapt to higher cellular oxidative demands…a vicious cycle of insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion can be initiated."

•Researchers at Kaiser Permanente gave pregnant women EMF meters to wear for 24 hours. The children of women whose exposure exceeded 2.5 milliGauss were more than six times as likely to be obese as teenagers than the children of mothers whose exposure were lower than that amount.

•Continual weight increases have also been observed in animals. A paper assessing this reviewed the weights of 20,000 animals from twenty-four populations representing eight species, including laboratory animals, house pets, and feral rats, both rural and urban. In all twenty-four populations, the animals' average weights rose over time. The average weight gain observed per decade spanned a wide range depending on the species (2.9%, 3.4%, 4.8%, 5.3%, 6.9%, 8.8%, 9.3%, 9.6%, 9.7%, 11.5%, and 33.6%) with the largest (33.6%) amount being observed for chimpanzees. The odds of this happening by chance were less than 10 billion to one, suggesting that some factor besides humans' processed diet is causing these changes.

Note: other studies have also reached the same conclusion in additional animal species.

•An unusual study decided to test the effect of prolonged exposure to 800 MHz radio waves. Twenty-four mice were irradiated at a power level of 43 milliwatts per square centimeter for two hours a day, five days a week, for three years. Four of the mice died from burn injuries (due to the strength of the EMFs), while a fifth mouse became so obese that it could not be extracted from the exposure compartment and died there.

Each of these points helps makes the case that EMFs could be responsible for a significant portion of the obesity we are facing or that some other agent which causes mitochondrial dysfunction (e.g., an environmental toxin) is responsible. When I asked the clinician I thought could best assess the question, they told me that EMFs could cause weight gain but only seem to be a concern for 10% or less of the population.

This doctor also believed zeta potential played a larger role in weight gain (which a few other doctors have believed as well) as an impaired zeta potential (which thickens water) seems to slow down mitochondrial respiration between 5-40% (typically in the 20-30% range). Interestingly, to some extent, this observation was also supported by another review paper a reader recently sent me (this is a bit technical, so feel free to skip it):

The mitochondrial ATP synthase (F0F1) is a rotary motor enzyme with a proton-driven F0 motor that is embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane and is connected to the ATP-driven F1 motor that protrudes into the mitochondrial matrix [305,306,307]. The higher viscosity of the medium can slow down the rotation of the F1 motor to reduce ATP synthesis not only in mitochondria [308] but also chloroplasts [309]. While ATPase turnover rates are more effective when detected by probes designed with lower viscous drag [310], viscous drag can dramatically slow the rate of rotation to 3% of the enzyme turnover rate in Escherichia coli [311].

Nonetheless, 100% efficiency of the F1 rotor can theoretically be achieved if the 120° power strokes rotate at a constant angular velocity [312]. However, power stroke and dwell duration are easily modified by viscosity. Viscous loads applied to the ATP F1 motor of E. coli can cause the increase in the duration of the 120° power stroke that is correlated to a 20-fold increase in the length of the dwell. Thus, the power stroke velocity is limited by the viscous load on the motor, and consequently, increases in transition time are the direct result of increases in viscosity and not from inhibition of the ATPase by other means [313]. A deeper analysis of viscosity sensitivity showed that viscous drag on rotations of the γ-subunit in the F1 motor [314] can cause variations of more than 5000-fold by using a variety of rotation probes [315].

Note: EMFs also directly disrupt zeta potential, which again illustrates how difficult some of these things are to untangle.

Endocrine Causes of Obesity

The primary system within our body which influences both food cravings and how much of a meal is stored as fat is the endocrine (hormonal) system. Not surprisingly, many researchers have focused on this area, and many believe modern humans are experiencing a significant degree of endocrine disruption.

Common Hormones

Typically when "hormones" are mentioned, three hormones (testosterone, progesterone, and estrogen) are the first that come to mind. Many physicians have medical practices built around optimizing hormonal levels. When abnormal hormone levels are evaluated for causing obesity, those three sex hormones (mainly estrogen and testosterone) are among the most commonly considered. Since the field of hormone medicine is quite complex, various opinions exist.

I, for example, believe that direct supplementation of hormones should be avoided until it is necessary (e.g., it is preferable to address the underlying cause of a hormonal deficiency rather than giving the missing hormone, and it is better to start it later in life).

Note: a similar belief exists in some schools of Chinese Medicine. Since the body will build a resistance to energy-providing herbs (e.g., Ginseng), those schools advocate waiting until you are older and really need them to begin using the herb.

I also believe that the exact form of the hormone matters, and the ones that are as close to what the body produces as possible (commonly referred to as "bio-identical" hormones) should be used as a variety of issues can emerge with non "bio-identical" ones.

While writing this article, I decided to solicit the opinions of the physician I know who has the most experience treating hormonal levels in a variety of conditions and the clinical success to support their approaches. To summarize what he told me [my comments are in brackets]:

I believe hormonal imbalances contribute to obesity but are not the primary cause [this is an important position to have as people are almost always biased to believe their approach is the most critical approach]. For example, a heavy emphasis is often placed on optimizing thyroid function, as low thyroid function is associated with weight gain and fatigue. My own experience has been that optimizing thyroid function makes patients feel better and provides them with noticeably more energy to function, but it does relatively little for losing weight or helping a patient control their weight unless they have overt hypothyroidism.

[I believe becoming hyperthyroid from overdosing on thyroid hormone (which is not healthy) can help with weight loss, and a longstanding issue in the weight loss supplement industry is thyroid hormone sometimes being added to those supplements.]

Generally speaking, excessive estrogen (in both genders) is the hormone that has the largest role in weight gain, as when it goes up, you consistently get a little more fat storage. In contrast, deficient testosterone has the second biggest effect. I have also seen human growth hormone be cited as a treatment for obesity, but my experience has been that it does not help. Additionally, when evaluating estrogen levels, a blood test (e.g., Quest Diagnostics) is the correct way to evaluate it for men, whereas women require a saliva test.

Typically, I find the most important hormone for women is progesterone. This is because if the progesterone to estrogen ratio becomes too low, a variety of common female issues onset (e.g., patients feel bad, they get bloated, their breasts become tender, they develop breast cysts, and breast cancer can be triggered). When appropriate progesterone dosing is provided, these issues will resolve. However, progesterone often causes women to gain 5-8 pounds, so I make a point to inform my patients that this will happen before they start progesterone.

With many pharmaceuticals, if you use them at a much lower dose than the standard dose and only in patients they are the most indicated for, you often have a dramatically better benefit-to-risk profile than that typically ascribed to the drug. In the case of estrogen, if it is excessive, I use an aromatase inhibitor (Arimidex) to lower estrogen

[Note: fat cells increase estrogen levels because they contain aromatase, an enzyme that synthesizes estrogen (e.g., by converting testosterone to estrogen)].

Arimidex (an aromatase inhibitor), when used as an adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, is dosed at 1 mg a day (7 mg a week). When indicated, I typically dose it at 0.5 mg for men 2-3 times a week (1-1.5 mg a week), whereas for women, I dose it at 2-5mg a week. I have a small number of patients who required a higher dose (men who required 5-7mg a week and women who needed 14mg/week), but these cases are very unusual.

[Note: natural but nowhere near as potent aromatase inhibitors also exist in cruciferous vegetables, and supplements like this one are also used by some of my colleagues to lower excessive estrogen].

Lastly, when treating low hormones, it is important to make sure you do not overdose the replacement hormone. One of the current fads in medicine is injecting pellets under the skin to ensure a constant dose of the needed hormone is administered to the patient. I do not like this approach because individuals who prescribe hormones, in general, tend to overdose them, and if the pellet approach is used, it’s not possible to back off and reduce the dose after the fact (typically, pellets spike the hormone level in the first month and then drop to a much lower level in the following months). However, this approach is becoming very popular because it can be billed at a higher rate as the pellet insertion itself is a billable procedure.

Additionally, as one ages (especially following menopause), the hormonal balances in the body change, and I often have people report that they found they had to radically change their diet when those changes occurred. Three other common instances where I see a need for a dietary change occur are:

•After a severe injury (e.g., I saw a long-term vegan who had a catastrophic car wreck that required ICU care and switched to eating meat because his body suddenly started craving it).

•If you migrate to a different climate (discussed in the first part of the series).

•As the seasons change (Staying Healthy With The Seasons is a classic on the subject). This concept is also present in holistic medical systems such as Chinese medicine and is discussed through a more conventional framework within The Fat Switch.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)

One popular weight loss method involves combining calorie restriction with injections of hCG, a hormone released to support a pregnancy (primarily at the start of it). There are many strong advocates of this diet, as it is a very effective method of weight loss (although this benefit is primarily seen in men). However, it also has some issues (e.g., I know one individual who did it and became permanently diabetic immediately afterward, and occasionally it seems to trigger immunological issues).

The biggest issue with this diet is an observation my integrative oncology colleague has made; it appears to be associated with triggering cancer (he had three patients who developed cancer six months to a year after doing the hCG diet). One of the more interesting models of cancers was put forward by Nicholas Gonzalez MD, who argued that cancers were the embryonic growth process (which is supported by hCG) having gone out of control.

Many patients have found Gonzalez’s cancer protocol worked for them. My colleague studied it in detail because it was one of the most helpful approaches he found for pancreatic cancer (which is one of the most challenging cancers to treat), and I suspect this is why he was able to draw the hCG connection. For this reason, my colleagues council patients considering this diet on this risk and also on the importance of not doing it repeatedly (as the sensitization to hCG increases each time the diet is repeated and each cancer he observed occurred after a repeated rather than initial attempt at the diet).

As far as we know, no one else prescribing the hCG diet is tracking cancer. If you do decide to do it, it is worth considering limiting the number of times you do it and being sure to space out each attempt from the one before.

Xenoestrogens

We are constantly exposed to many compounds that behave like estrogens in the environment and thus are commonly referred to as endocrine disruptors. These include soy, common chemicals used to make plastics, certain pesticides, certain herbicides, and birth control pills that persist in the water supply (since once urinated out, the water is recycled back to the drinking supply after being “treated” at a plant), along with a few outlawed but persistent chemicals (e.g., DDT and the PCBs).

Many believe that our widespread xenoestrogen exposure causes obesity, depression, lowered testosterone, and feminization or intersex characteristics (e.g., the herbicide Alex Jones famously ranted about atrazine, has been known for decades to make frogs become hermaphroditic). For those interested in studying the data detailing the adverse effects of xenoestrogens, the best resource I have come across is the audiobook Estrogeneration: How Estrogenics Are Making You Fat, Sick, and Infertile.

Note: estrogen-containing birth control pills are also frequently associated with weight gain in the recipients. Other pharmaceuticals that do not contain xenoestrogens (e.g., certain antidepressants and antipsychotics) are also associated with weight gain (and in the case of olanzapine diabetes too).

Obesogens

Since the correlation between sugar (or high fructose corn syrup) exposure and the incidence of diabetes does not match up perfectly, many suspect that it is a contributing rather than a primary factor. This has led to researchers gradually trying to determine if specific environmental exposures (termed obesogens) increase the likelihood of obesity and diabetes.

Joseph Pizorno (a leader in the naturopathic profession), for example, has made a strong case that obesogenic chemicals or heavy metals are the primary cause of the diabetes epidemic. This is because:

•The production of those chemicals matches the rates of diabetes:

•Individuals with higher exposures to obesogens have a proportionally higher rate of diabetes:

•Numerous mechanisms and evidence exist to show how these obesogens contribute to diabetes. Pizzorno then estimated the contribution of each of these obesogens to be as follows:

Note: Pizzorno later published The Toxin Solution, a book (and audiobook) that provides a much more detailed discussion of this subject.

Many of the obesogens are also xenoestrogens, and many different obesogens are found in processed foods. A detailed list of the obesogens (alongside a comprehensive review of the supporting evidence for it) can be found in this article. One of the most important points it makes is how many food additives that are generally considered safe (GRAS) are only in their infancy for being studied for their contributions to obesity. This is a bit unbelievable given that many consider obesity to be the single greatest problem with processed food.

Note: Ever since the FDA was founded, food additives with significant toxicity have received the GRAS designation (despite it being unjustified). The first chief of the FDA wrote a book detailing how hard he fought to make the agency do its job and mentioned that he was strong-armed into allowing aluminum to be added to the food supply. I believe the widespread presence of aluminum is a key cause of illness in society (due to aluminum’s adverse effects on zeta potential), and despite being deemed GRAS, the safety of aluminum has never been studied.

Since there are so many potential obesogens, it becomes quite difficult to determine which ones have the most significant impact. The one person I know who looked at this question in their practice concluded the most influential obesogens were high fructose corn syrup, acrylamides (from potato chips), yellow dyes, and red dyes.

In addition to chemical obesogens, many now believe that factors which adversely affect your normal sleep rhythm (discussed extensively in this article), such as light exposure at night, also trigger obesity. Furthermore, because so many hormonal systems are linked to each other (e.g., the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenals axis), many factors you would not expect to cause issues can rapidly ripple out into the whole body.

For example, chronic stress is known to cause HPA axis dysfunction and is one of the factors most strongly linked to heart disease. Lastly, one of my mentors, for example, who has had significant success treating diabetes, has found the key issue in the disease is usually a problem within the pituitary gland (e.g., a cranial compression).

Finally, a significant link exists between the gut microbiome and obesity, as good bacteria tend to cause weight loss, while bad bacteria cause weight gain. This is unfortunate because “bad” bacteria seem to create cravings for unhealthy and often sugary processed foods (our best guess is they account for 30-40% of the cravings) and then come to dominate the gut microbiome because they are the best adapted to eating those foods.

Although many approaches exist, I believe the best way to break this perpetuating cycle is to completely stop eating processed foods and then deal with the withdrawals until the desire for the foods disappears. While this works, I am unsure if the processes I observe (the cravings disappearing) are due to the gut flora changing or something else.

Note: conventionally raised livestock are typically fed large amounts of antibiotics, which causes them to gain weight and thus be more profitable when they are butchered. This weight gain occurs because the antibiotics disproportionately eliminate the “good bacteria” which prevent weight gain, allowing the obesogenic ones to take over the gut flora. This process has been clearly demonstrated in animals, whereas there is more of a debate if a course of antibiotics or eating antibiotic-laden meat also triggers this process in humans. Some of my colleagues who treat Lyme have said they vastly prefer IV antibiotics because they find if they do long-term administration of an oral antibiotic, that devastates the gut, creating a lot of additional issues that need to be fixed later.

Cortisol Dysregulation

Dr. Mercola recently reached out to me and asked me to look into the work of Ray Peat (deceased) and his best student Georgi Dinkov, stating that he had learned an immense amount from their work and that they had made him realize many things he had spent fifty years believing about diet and nutrition were wrong. This caught my attention because, generally, in situations like that, people will not want to acknowledge evidence challenging their deep-seated beliefs (especially if they publicly promoted it—consider the cases of the raw vegan influencers discussed in the previous article). I believe this admission is reflective of someone who has an unusual devotion to uncovering the truth, something sadly lacking in medicine.

An overview of their model is covered in this article. To briefly summarize it:

•Many individuals find the ketogenic diet initially works for them, but then, over time, the benefits from it plateau, which argues that some of the premises underlying it may not be correct.

•When the body is low in sugar (which happens when you only eat fat), stress hormones are activated to raise blood sugar.

•One of those hormones is cortisol. One medical syndrome, Cushing’s disease, comes from abnormally high cortisol and is known to cause significant abdominal fat to accumulate in patients suffering from it. The consensus within the medical field is that abdominal fat is “bad” fat, and health interventions are often targeted at attempting to reduce abdominal fat. A key consequence of HPA axis dysfunction (which often arises from chronic stress and, as mentioned above, is one of the factors most strongly linked to heart disease) is cortisol dysregulation. So this means we may have put too much of our focus into abdominal fat rather than the cortisol that creates it.

•One of the common things integrative medicine practitioners test patients for is their cortisol levels throughout the day. This is because it has been found that cortisol increases at the wrong times during the day (which is often a result of a dysregulated sleep cycle and circadian rhythm) or are too high, this creates a variety of issues, including fatigue and inappropriate energy levels throughout the day.

My take is it's an endocrine problem," Dinkov says. "So if you're struggling with weight you cannot lose, I think it's a good idea to do a blood work [panel] for the steroids … Every single person that has been struggling with excessive weight that has emailed [me] their blood results, without exception, their cortisol is either high-normal or above the range, both the AM and the PM value.

This indicates that a critical endocrine disruption underlying obesity and diabetes is cortisol dysfunction.

•To my knowledge, there have been three anticancer diets that demonstrated a significant degree of success—Gerson Therapy (based around juicing, and which relatively few people know required the juice to be cold pressed and consumed immediately after juicing so its vitality as not lost), The Budwig Diet (based around correcting the fats in the body and making the body able to absorb sunlight properly), and the previously mentioned Gonzalez Protocol.

Gonzalez studied under acclaimed nutritionists who promoted a ketogenic diet and observed that while it appeared to help obese and diabetic patients, it did not help the cancer patients who visited their clinics. Gonzalez instead developed an anticancer diet that utilized a mix of healthy carbohydrates. Despite his success (especially with pancreatic cancer), his approach is still relatively unknown, and many in the holistic field believe that a ketogenic diet cures cancer. As far as I know, the only place ketogenic diets have been shown to treat cancers is for cancers of the nervous system (and in parallel, ketogenic diets offer help for certain nervous system disorders like epilepsy).

In their interview, Dinkov provided one of the better explanations for why ketogenic diets fail to treat cancer—excessive fats inhibit the mitochondria from being able to burn sugar (a common dysfunction seen in cancer and, as discussed above, diabetes).

•Many of the issues with carbs arise not from carbs themselves but rather from starches (which are also plentiful in high fructose corn syrup). Some of the best sources of starch-less carbs are raw honey, ripe fruit, and cane sugar. I found this interesting because back when I had to take the board examinations throughout medical school (which are very long tests), I decided that proper nutrition (so you stayed awake throughout the examination) was vital for succeeding on them. I knew that the best fuel source for the brain was glucose. However, I also knew, simultaneously, that digesting a starch would often make you feel tired (thus negating my goal for the examinations), so I settled on eating raw honey (as it is predigested into fructose and glucose) before the test and at each break. This worked well, and other students have since copied the approach.

•They believe the optimal diet has a roughly even mix of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats. Personally, I think unless you are trying to accomplish a particular goal, simple, natural, and balanced diets that are done in moderation and feel right for the body tend to be the best option. Similarly, as discussed in the first part of this series, this is why I believe it is so important to listen to what your body wants to do (rather than following an extreme diet) and why ideally, I think the foods you eat should be fresh local foods (e.g., grown from your own garden).

Adaptive Responses

A longstanding belief within the holistic medical field is that many of the things we label as diseases are instead adaptive responses of the body that have become maladaptive due to the scenario where the response activates not matching what the response originally evolved to handle.

In the case of obesity, it is well known that fat evolved as a way for animals to keep themselves warm and a way for them to survive prolonged periods without eating (e.g., camels are well known for doing this). A case can also be made (discussed within The Fat Switch) that consuming significant amounts of fructose or uric acid (particularly when they are also deficient in vitamin C) induces diabetes and weight gain so that fat can be stored during the summer, making it possible to survive the winter.

Within the natural medicine schools, it is frequently thought that fat functions as a protective mechanism for the body to store toxins the organs of detoxification (e.g., the kidneys) can’t presently handle in the bloodstream. Many toxins are fat soluble, and when individuals fast, those with a higher body burden of toxins typically experience the most difficulty fasting (as they feel awful from what was stored in their system).

In addition to the many anecdotal reports I have heard of this, the most evident proof of the phenomena I have come across has been with marijuana, since by being fat soluble, some of what is consumed becomes stored in the fat, and then later returns to the blood stream where it can again be detected. Since there is a social interest in understanding this process, research has been conducted (e.g., this study) and has proven it occurs.

However, while toxins are stored in fat, it’s much harder to state with certainty if their presence directly triggers the body to store its calories as fat. So, I openly admit that while I think this occurs (based on our observations), I could also see it as being that the two are correlated (e.g., the toxin is also an endocrine disrupter, so it will trigger fat storage), but that there is no adaptive response within the body to store the toxin as fat. Nonetheless, since it is a valuable model to explain to patients why eating certain things causes them to get fat, I often share it with the caveat I may have the actual mechanism of their weight gain wrong.

Note: this logic can also be used to argue why things that impair zeta potential appear to cause weight gain. In that model, the fat stores (zeta potential disrupting) positive ions the normal mechanisms for handling (e.g., the kidneys excreting harmful positive ions) cannot address until something is done to restore the zeta potential.

Diabetic Sensitization

In the current era, we are facing an unprecedented wave of chronic illness, much of which is neurological or autoimmune in nature and which many (myself included) believe are at least partly due to the continual increase in vaccination throughout the population.

In the case of diabetes, one form (Type 1 diabetes—which requires lifetime insulin administration) is considered to be an autoimmune disorder as the immune system destroys the part of the pancreas that makes insulin (e.g., I had a patient who developed it after receiving the HPV vaccine). Conversely, although Type 2 diabetes (the more common form) is typically considered a lifestyle disorder rather than an autoimmune one, there is also a large body of evidence linking it to immune dysregulation.

At this point, we believe type 2 diabetes is most likely immunological in nature for two reasons:

•First, we’ve tried a variety of integrative therapies that appear to be indicated for the specific patient (e.g., treatment of a known parasite infection), and while each helps a bit, they rarely had a significant effect on the patient’s diabetes.

•Secondly, we have seen numerous cases where a sensitizing trigger caused an individual to develop diabetes. One of the best examples was a colleague’s relative who went on a deer hunting trip, and then every member of his group (who all ate the same deer) subsequently developed diabetes. We felt the only thing that could have accounted for this cohort example was a vaccine their entire unit got in the military or something that was in the deer (e.g., a parasite or possibly CWD).

At this point, we believe this autoimmune process is likely due to either certain foods or vaccinations. When considering this process, it is also helpful to note that vaccinations can often create a propensity to food allergies, and repeated exposure to a potential allergen often sensitizes the body to develop a more severe reaction to the allergen in the future (this, for example, is one of the best existing models to explain why each successive COVID-19 vaccine is more likely to cause a severe injury than the one which preceded it). We have also suspected a toxic metal may be involved, but we are not confident in that hypothesis because we have never observed chelation therapy cure diabetes.

Note: another colleague adamantly believes diabetes is caused by a rapid shift in the baseline feeding pattern the body has adapted to as she has seen multiple cases of patients who attempted to lose weight rapidly shift their diet and then develop diabetes afterwards. I have personally seen this happen following a juice fast done in conjunction with the hCG diet.

Fat Sensitization

Throughout this series, in parallel to emphasizing that the “optimal diet” is likely impossible to find because there is so much variability in individual nutritional requirements, I have alluded to many factors which can promote weight gain but so far avoided characterizing any (besides processed foods) as a primary cause.

Presently, a few colleagues and I believe the primary issue with obesity is that individuals will become sensitized to certain foods, and once consumed, these foods signal the endocrine system to store the calories it consumes as fat. This signal can last up to 4-5 days, so if the fat-signaling food is eaten more than once a week, even if an appropriate number of calories are consumed, weight gain often results as there is a continual signal for the body to store fat.

Conversely, they will lose weight if the fat-signaling food is no longer eaten. This is why you occasionally meet people who say they lost 10 pounds after giving up gluten (as it was their fat signaler), whereas for many others doing so had no effect on their weight.

Note: many also suspect the issue with gluten is not gluten itself but the high glyphosate content of wheat that is not organic.

This dynamic is particularly problematic because the fat-signaling food is often something individuals crave, and in some cases, rather than being harmful, is otherwise good for them. For example, the person I know who originally discovered this periodically found cream stimulates him to gain weight, but eating cream also helps his body build muscle, so only he has cream a few times a week and consumes it in conjunction with when he lifts weights. As a result, he has a bit of a belly but is also very muscular.

This signaling process helps to explain one of Trump’s well-known tweets:

Aspartame (a toxic artificial sweetener) frequently signals the body to store fat. Its presence explains why individuals who consume Diet Pepsi or Diet Coke often gain more weight than those who drink regular (high-calorie) sodas. Furthermore, this link is common enough that studies have observed it, and a few endocrine signaling mechanisms have been established to explain it (see this review, this article, and this article). Due to its effects on the endocrine system (and possibly its known effects on neurological signaling), patients frequently become partially addicted to aspartame and will not give it up even if advised to by their physicians.

Conversely, this property can sometimes also be life saving:

Cachexia is the weakness and emaciation commonly associated with serious illness, such as cancer [and from chemotherapy], HIV/AIDS ('slim disease') and tuberculosis, and seen after burns, major surgery or trauma.

In cachectic patients (which also includes elderly individuals who appear to be on their way out), restoring weight is vital for their survival but often impossible to accomplish. One of my colleagues realized the fat-signaling properties of Diet Pepsi after he noticed many of his patients who drank Diet Pepsi became diabetic, and pioneered having cachectic patients consume a small amount of it (after first holding it in their mouths) a few times a week for 3-6 weeks. This addressed many cases of cachexia and was life-saving for all practical purposes.

Note: irrespective of Trump’s tweet, my colleague found Diet Pepsi is a much stronger fat signaler than Diet Coke.

At the same time, even though aspartame is one of the most reliable fat-signalers out there, high fructose corn syrup also is a major contributor due to how it affects the small intestine and the manner in which it triggers a large release of insulin.

So, one of the most important things to identify through trial and error is what foods your endocrine system has become sensitized to (e.g., are you the guy who always gains weight when you eat potatoes, or are you the lady who can’t resist donuts but always gains pounds from them—both of which we have seen in clinical practice).

To share a personal example, one of the things that was immensely frustrating for me was discovering that my body had become sensitized to avocados (which I suspect was due to how frequently I ate them), resulting in avocados becoming a fat signaler for me. The ironic thing about this was that a key part of why I started eating avocados so frequently (beyond the fact I like the taste) was because, due to being mostly fat, I assumed under the ketogenic diet theory, they would not cause me to gain weight.

There are a few different approaches to addressing this problem. The first is to follow a classical nutritional adage and have a significant degree of variability in your diet so you are not eating the same foods multiple times per week. The second is to consider your potential fat triggers and then experiment with removing them to see which ultimately matters for your weight loss—especially if you are eating a normal (or restricted) amount of calories but not losing weight.

A key thing to remember in this model is that you don’t need very much of the food to trigger its fat signaling. For example, we have had a few patients who otherwise avoided dairy but loved to put half and half in their coffee occasionally, and it did not occur to them this was causing them to gain weight or even that they were exposing themselves to a potential fat signaler multiple times per week until it was pointed out to them.

Overcoming Food Addiction

For a long time, I felt the best way to overcome a food addiction was to cold turkey until the cravings for it disappeared. Unfortunately, many patients simply can’t do this (we have tried more approaches than I can count to bridge this gap), so while I follow that advice, I do not believe it is ethical to rely upon that approach for patients. This situation is particularly problematic because people are often addicted to their fat sensitizer. For this reason, we typically do not push patients to avoid their fat sensitizer unless they appear to be psychologically capable of withdrawing from it.

Appetite suppressants (one potential solution to this problem) have been developed but tend to have significant side effects. For example, fen-phen was a miraculous weight loss product for patients (and helped with other addictions) but was “shown to cause potentially fatal pulmonary hypertension and heart valve problems, which eventually led to its withdrawal in 1997 and legal damages of over $13 billion.” Similar recreational amphetamine usage suppresses appetite, and some even try it specifically to lose weight (which is often followed by the much worse side effect of becoming a meth addict).

One of the less harmful and widely available options is nicotine (proven to suppress the appetite), which helps explain why people who smoke tend to be thinner than non-smokers, and why they often put on weight once they stop smoking. This has resulted in certain doctors trying nicotine patches to help with weight loss. Still, since nicotine (especially at regular doses) creates adverse health effects and can become an addiction (even when used in this manner), I am understandably hesitant to endorse this approach.

Fortunately, at last, there appears to have been a safer solution that was developed for this issue.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a hormone secreted after a meal that reduces the desire to eat or drink (since it promotes a feeling of fullness), induces the secretion of insulin, and stimulates the production of insulin in the pancreas (insufficient production of insulin in the pancreas is a common issue in diabetes).

Note: one way GLP-1 increases fullness is by causing food to stay in the stomach, which helps to explain why the most common side effect of one drug that mimics GLP-1 is nausea.

GLP-1 also improves insulin sensitivity (a key issue in diabetes) and glucose uptake throughout the body. It also has protective effects on organs throughout the body, particularly in the brain, where it appears to counteract many of the degenerative processes associated with conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Since GLP-1 sensitivity (unlike insulin sensitivity) is not impaired in diabetes and addresses many different components of this disorder, it has been a heavy focus in diabetes research. Nonetheless, much still needs to be understood about the functions of this hormone.

Presently, a bit of a debate exists on if GLP-1 is reduced in type 2 diabetes as some studies have shown it is, while reviews of the existing literature have reached opposing conclusions (e.g., compare this review to this review). Based on everything I’ve looked at, I am presently inclined to believe GLP-1 is impaired in type 2 diabetes, but I may be mistaken here. Additionally, glucose is better at triggering the release of GLP-1 than fructose, which may partly explain why our switch from sugar to high fructose corn syrup has contributed to obesity and diabetes.

GLP-1 is produced and secreted by intestinal enteroendocrine L-cells and specific neurons within the nucleus of the solitary tract of the brainstem. I believe some of the confusion regarding if GLP-I secretion is impaired in diabetics arises from the fact there are direct connections between the regions in the brain that produce GLP-1 and the regions of the brain affected by it (so blood tests would not detect those secretions).

A tentative hypothesis I have to explain the present diabetes debacle is based on Andrew Moulden’s work, who I believe developed one of the best models for explaining vaccine injury (which I have spent a lot of time trying to elucidate all the components of). He was able to demonstrate that vaccines, through lowering zeta potential within the body (and triggering white blood cells to enter smaller blood vessels where their presence would suffice to obstruct circulation), created microstrokes that disproportionately affected the regions of the brain which had weaker blood supplies (known as watershed areas) and smaller blood vessels (which are more vulnerable to this process).

Since all of that applies to the cranial nerves, Moulden could frequently diagnose vaccine injuries through overt or subtle neurological signs of an impaired cranial nerve, especially the nerve that allows each eye to look to the side. Similarly, I have noticed that impairment (how the eye moves as it looks to the side) has also been something I’ve frequently seen develop in colleagues who received the COVID-19 vaccine.

The primary area of the brain, which secretes GLP-1 (the solitary tract’s nucleus), is located in a region not too far from the cranial nerves that vaccines commonly injure, and I thus suspect may also be vulnerable to the same process. Assuming that is the case, part of the reason repeated vaccination sensitizes individuals to both diabetes and food cravings is that it disables the production of GLP-1 in the brain. It may also affect the small intestine’s production of GLP-1 (e.g., through an autoimmune process), but this is much harder to say, and it is more likely that the process is directly affected by the foods you eat.

Note: Drugs that mimic the effects of GLP-1 have been shown to address not only food cravings but also many other addictions. This suggests that if there is widespread impairment of GLP-1 production in the brain (which will be very difficult to study), widespread societal consequences follow from it. I have also wondered if a key component of food addiction is an addiction to cortisol being released by fat-sensitizing foods, but I have not had any way to evaluate this hypothesis thus far.

Ozempic

I am typically highly cynical of any new pharmaceutical that enters the market. I thus have a rule not to touch any new drug unless it has been out for at least seven years (as this is normally how long it takes to discover the major side effects).

That said, I have lost count of how many people have reached out to me to share that Ozempic (a drug that mirrors the effects of GLP-1) is fantastic for diabetes (especially obese diabetics) and is the first drug in ages that seemed to be a breakthrough in the treatment of diabetes. Although Ozempic is not completely safe (e.g., it can cause gastrointestinal symptoms, and there is some data associating it with pancreatic cancer), its benefit to patients with uncontrolled diabetes may justify its potential risk.

Note: we have also observed that long-term users of Ozempic often experience fatigue (typically around a year of use), so it’s much better to use it for 3-4 months than take a break.

One of the interesting side effects of Ozempic is that it causes weight loss by suppressing appetite, and this effect is pronounced enough that a few years later, the FDA approved a second formulation of the same drug (Wegovy) specifically as a treatment for weight loss. Once this side effect was recognized, one of my colleagues realized it could be used to eliminate food cravings, which anchored patients to never giving up their fat-sensitizing foods.

This application has been revolutionary for dealing with this issue (as previously, it was either impossible or unsafe to provide an intervention that could successfully compel the patient to stop eating the food if they were already addicted to it). However, when it is used in this manner (which must be done in coordination with the patient making an active effort to overcome their craving for a specific food), a much lower dose (0.25-0.5 mg) than the typical 1-2 mg dose. Although it is too soon to say, I am hopeful this lower dose will avoid many of the side effects being seen (along with others that likely will be discovered later) from the higher doses of the drug.

Note: it has been observed that two-thirds of those on Ozempic had regained the weight they lost on the drug a year after stopping it. This argues the drug is an excellent product (as it will generate repeating sales) but also that it may not be the best way to lose weight (especially since the potential toxicity of pharmaceuticals often increases with each successive administration). This again argues instead for it being used in a mindful manner aimed at breaking food addictions rather than as a magic weight loss solution that does not require any work on the patient’s part.

How Dangerous is Obesity?

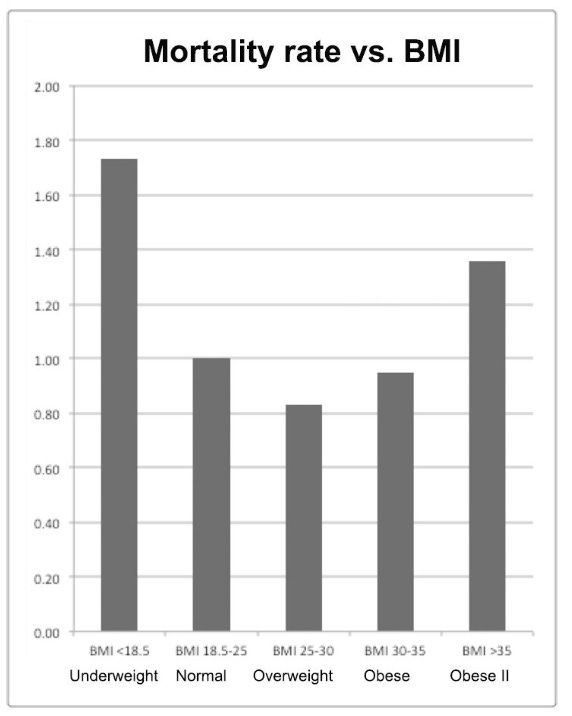

One commonly held belief is that being overweight is terrible for your health, while being skinny is ideal. When Malcolm Kendrick investigated this question in detail, he discovered that existing evidence actually argues that being slightly overweight is ideal for health, while being underweight or significantly overweight worsened it (with the greatest risk resulting from being underweight).

Note: the argument put forward by this paper may be partially distorted by the fact the elderly often become malnourished and lose weight at the end of their lives. From reviewing the study, I could not assess the degree to which that affected the study’s conclusions.

Since this violates the existing consensus, as is seen for many other controversial topics, any paper with data showing being moderately overweight does not put the patient at risk of dying (e.g., this study or this study) will try to avoid stating that overtly so the paper can make it to publication. Given that a healthy degree of body fat increases longevity, this is another reason why it may not be in everyone’s interest to overuse weight loss approaches like Ozempic.

Note: One of the best metaphors I know of for our attitudes towards being overweight is that seen with bodybuilding. While weight training does provide specific health benefits (e.g., it can strengthen ligaments in hyper-mobile individuals and increases testosterone production in men), excessive bodybuilding is detrimental to health.

I and many others have observed bodybuilders tend to suffer from various conditions as they age (along with dying younger). I believe these observations are due to the significant tension weight lifting creates throughout the body, which amongst other things, impairs essential fluid circulation. Numerous colleagues and I view habitual and excessive bodybuilding as being in the same family of conditions as body dysmorphias like anorexia. Outside observers of our culture often remark that “one of biggest mistakes Americans make is that they tend to assume if something is good for you, more of it is better, and as the two previous examples show, this comes up quite frequently.

One of the most significant issues with Ozempic is that in addition to the obese diabetics who benefit from it (and likely cannot sufficiently produce GLP-1 on their own), many people who want slim figures are also clamoring for the drug and are being prescribed it for a use that it was not intended to be used for at the time of its approval. As a result, we are seeing more and more patients who should have never been prescribed the drug and are taking enough of it (often even overdosing) to drive themselves into cachexia. These patients are easy to identify as they don’t look normal and have a somewhat sick and somewhat anorexic appearance.

Because aesthetic weight loss represents such a large market (which the FDA is actively promoting with the pharmaceutical industry), I do not believe anything will be done to stop this off-label drug misuse. It is very likely a few years down the road, Ozempic will be seen in a much more negative light than it is now. It’s wishful thinking on my part, but I sincerely hope one day, our society will be able to recognize what constitutes a healthy body weight and put out messages that encourage it.

My Approach to Weightloss

I hope that throughout this series, I have provided some useful insights into the causes of obesity and which diet to follow. I aimed to offer perspectives you had not heard before and to simplify a remarkably complex subject.

While I try to eat a decent diet, which I feel is better than what at least 90% of America eat, and am typically not overweight, I still gain weight, especially when I get careless when something else shifts my focus in life (e.g., everyone noticed I became a noticeably chubby over the last year and a half which was due all the time I’ve spent trying to put out the information I felt would help the current disaster we are in).

The weight loss industry is quite predatory (e.g., internet marketers have told me one of the most profitable products to push has always been dubious weight loss products they do not even believe work), and given the money involved, I am quite curious to see how far the pharmaceutical industry will go with their new GLP-1 blockbusters. Throughout my life, like all of you, I have lost count of how many almost comical weight loss advertisements I have come across:

Earlier this year, I decided I needed to deal with my recent weight issues. I used my preferred approach (which is very simple, affordable, and effectively addresses many of the issues detailed throughout this series). Before starting it, I told a few of my more conventional colleagues what I was planning to do because I felt more people needed to be aware of it and then tracked how I did. I lost 31 pounds in 30 days, waited a few days, did a bit more, lost 5 more, gradually gained 7 pounds back, and have remained at 29 pounds below where I started. I believe I could have lost a lot more weight with this approach, but my goal was to have a healthy weight (30 pounds below where I started) so I stopped.

A few people then asked me to write about it. Due to the nature of this approach and the potential issues that can arise from doing it incorrectly, I apologize in advance but the audience for it needs to be limited by a paywall.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Forgotten Side of Medicine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.