What They Don’t Tell You About Anxiety and The Dangers of Benzodiazepines

The forgotten treatments for anxiety and the immense dangers of inappropriately prescribed benzodiazepines

Story at a Glance:

•Selling addictive drugs is a highly reliable business model, and over the years, a variety of questionable drugs have been pushed upon us that target the inhibitory system of the brain alcohol also acts upon.

•The current preferred product, benzodiazepines (benzos), have a significant number of issues (particularly in the elderly), such as causing cognitive impairment, lightheadedness, poor coordination and fatigue (which collectively increase the risk of car accidents or falls), harming fetuses, and worsening the symptoms they treat (e.g., insomnia, anxiety, muscle spasms). Worst of all, they can cause respiratory depression and thus lethal overdoses (especially when combined with opioids).

•One of the most insidious issues with benzodiazepines is that they quickly create a physiologic dependence, and as a result, benzodiazepine addiction has been a widespread problem for decades.

•Unfortunately, while many of the issues with benzodiazepines (which in certain cases are very helpful) could be avoided with appropriate prescribing, the 15 minute visits created by insurance-run medicine makes physicians rarely have the time needed to appropriately prescribe them. As a result many who should not be on benzodiazepines are, and sadly, often are for decades.

•Many different types of anxiety exist (with different root causes and treatments). Unfortunately, medicine frequently erroneously views anxiety as a single disease entity, and as such, often treats it in a manner that is not actually indicated for their type of anxiety.

•This article will discuss the different types of anxiety, their root causes (much of which result from the unhealthy lifestyle modern living puts us in), the most effective natural (or conventional) treatments we have found for anxiety, and the most effective strategies for navigating the challenging process of withdrawing from benzodiazepines.

Note: in a recent article on the immense dangers of SSRIs, I posted a poll asking if there was a reader interest in this topic. As there many were, I spent the last week working on this article.

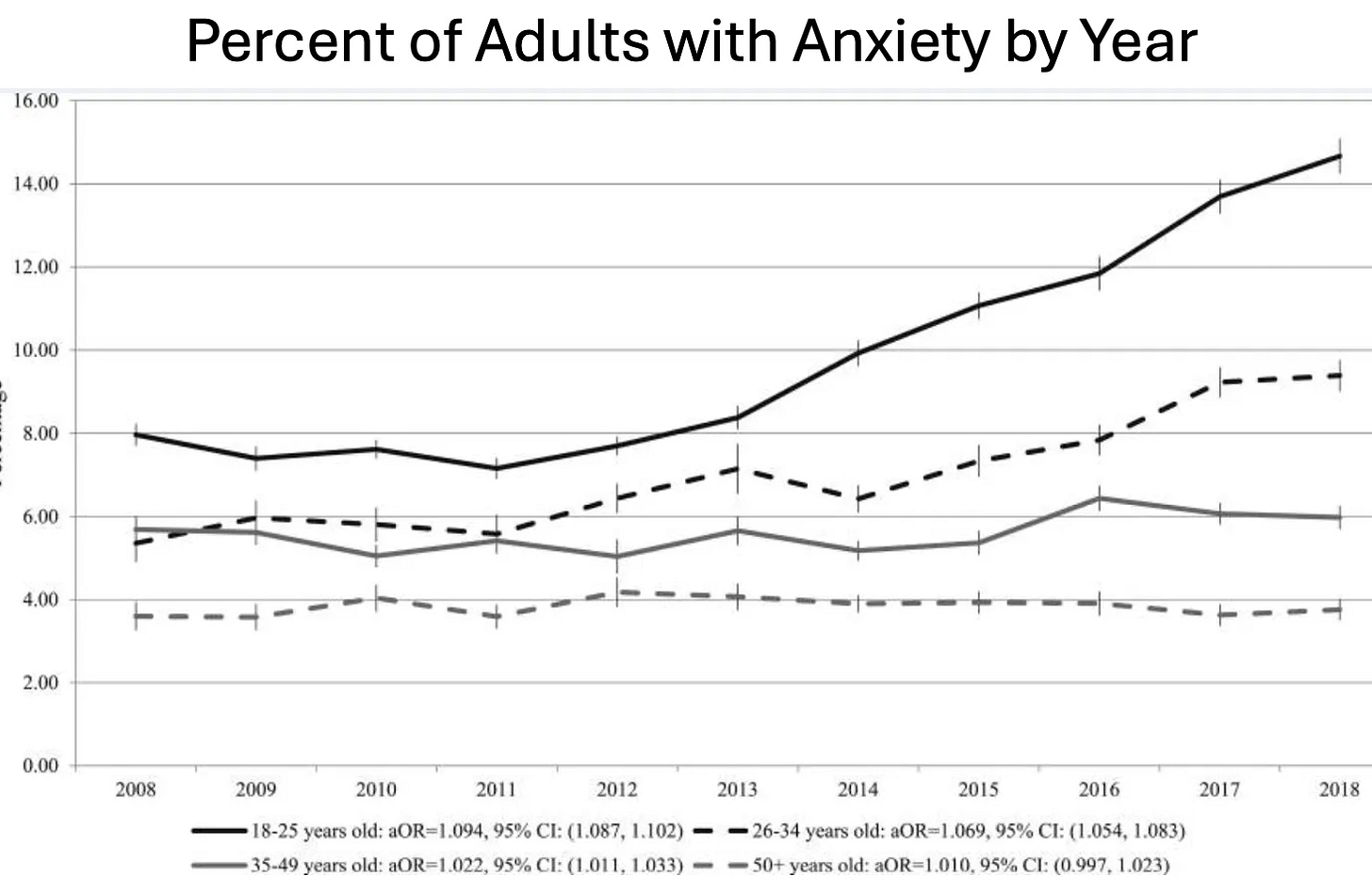

Many consider anxiety to be the disease of the modern age. It is thus one of the most significant disease markets in America (e.g., from 2001-2004, approximately 19.1% of American adults had an anxiety disorder. In 2007, 36.8 billion was spent on medical care for anxiety and mood disorders). Yet despite spending billions on anxiety, rather than be appropriately addressed (like many other industries that depend upon the perpetuation of the problem they “solve”), it has only increased.

Note: a recent survey found slightly over half of young adults (18-26) now suffer from anxiety, 43% have panic attacks, a third take anxiety medications, 54% found they became worse in 2023, and 26% of them were diagnosed with a new mental health condition due to COVID-19.

All of this suggests we may not be utilizing the best approach to deal with anxiety—particularly since the drugs used to treat it are some of the most problematic ones on the market.

The GABA System

Human physiology relies upon competing systems present at many different scales, which collectively hold the body in a state of equilibrium. Most pharmaceutical drugs, in turn, alter some of those regulating systems (typically by activating or inhibiting an enzyme or receptor) so the body can be shifted to a baseline deemed necessary for health. On one hand, this is an effective approach as it allows small doses of a therapeutic to rapidly exert change throughout the body. However, it frequently leads to a significant number of problems as:

•Drugs will often affect other systems besides their target (due to the significant similarity between many proteins in the body).

•Each of those regulatory systems often interacts with a wide range of things in the body, so if you stimulate or inhibit one, it can create a variety of unintended consequences.

•One of the ways the body regulates itself is by reducing overactive receptors and increasing under-active ones. Because of this, if a drug targets a specific receptor, a tolerance to it will often develop (as the receptor becomes harder to activate), which can require more of the drug to be administered as time progresses or withdrawals to trigger when it stops.

This final point is particularly consequential for drugs that affect the nervous system, as they rely upon a variety of stimulating and inhibiting processes, so artificially triggering either of those can subsequently cause withdrawals and hence create addictions.

Note: hooking people on neurologically addictive drugs has long been one of the most reliable business models, and in addition to being done by criminals, at many times was done by the state (e.g., consider England’s opium wars against China) or pharmaceutical companies (e.g., with heroin, cocaine, morphine, and methamphetamine in the early 1900s or more recently with synthetic opioids). When you review these cases, the drug dealer will frequently insist their product is safe and not addictive but typically will eventually be forced to stop selling it once too much social harm is created by their business model (e.g., the current opioid crisis).

Human neurology works by having nerve cells (neurons) connected to each other in a complex lattice that are continually giving signals to other neurons either to fire or not fire, with each neuron being calibrated to fire once it receives a sufficient stimulatory input. This is a beautiful system that makes much of life possible, but when it goes awry, a significant number of debilitating medical disorders emerge.

Within the brain, the most common inhibitory neurotransmitter is Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA), which works by changing the flow of chloride ions in and out of neurons. In turn, a large number of psychoactive drugs (particularly calming or sedating drugs) target the GABA system. Many of these (e.g., alcohol, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines), rather than directly activating GABA receptors, function by enhancing the effect GABA within the brain will have on GABA receptors. As you might expect, like alcohol, GABA drugs can often be highly addictive.

Note: unlike drugs that target the GABA system, supplements that simply contain GABA are not considered to be addictive. That said, I have seen a few very sensitive patients develop the withdrawals seen with GABA drugs after using liposomal GABA (a more potent preparation of GABA).

The History of Benzodiazepines

The first barbiturate used for medical purposes, barbital, was discovered in 1903, and once recognized to be an effective sedative, was quickly marketed (as Veronal). Following Veronal's success, various modifications were explored, and in 1912, phenobarbital was discovered and marketed to the world (as Luminal) and rapidly adopted by the medical system (after which many other barbiturates were brought to market).

The popularity of barbiturates arose from the fact they could treat anxiety, insomnia, epilepsy, and mania and sedate patients for anesthesia—all of which were extremely useful in medical practice, especially since the available pharmacologic treatments were much more limited at the time.

Note: barbiturates were also sometimes used to treat tremors, reduce pain, and for narcoanalysis (a form of hypnotic psychotherapy).

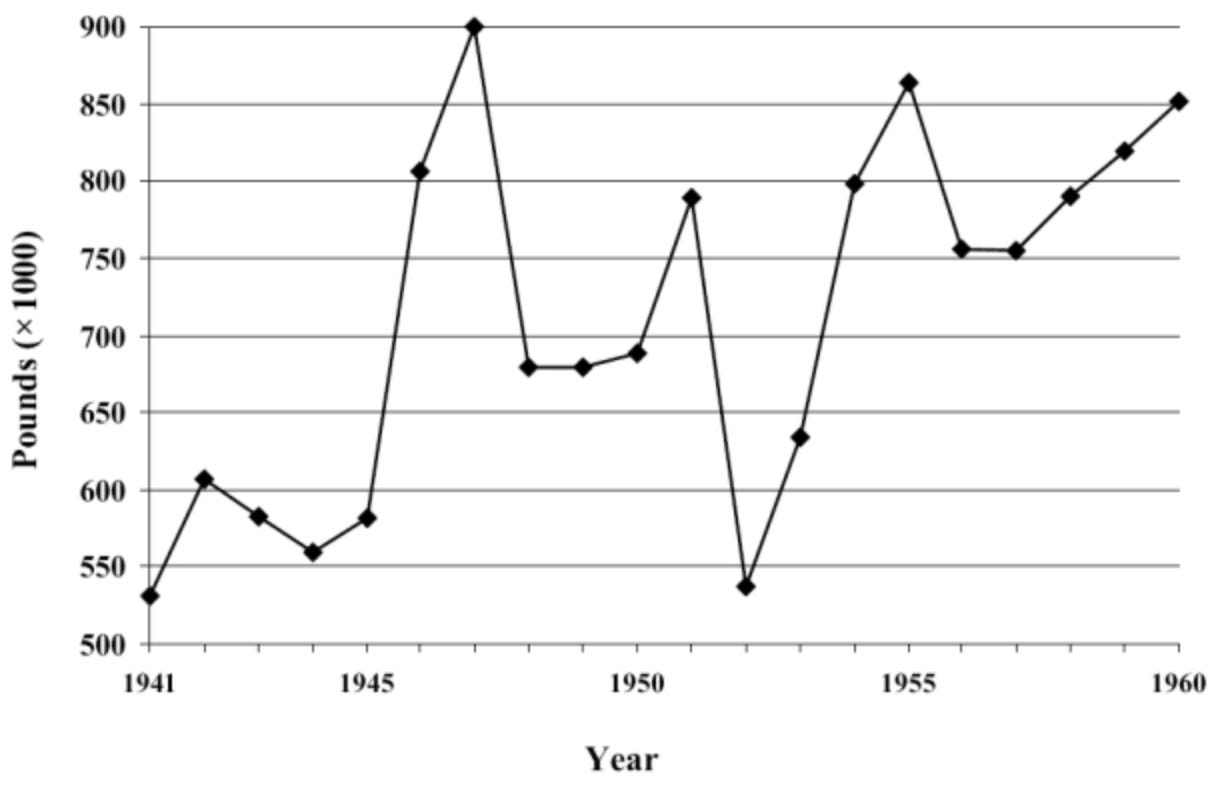

Because of this, barbiturates became very popular (e.g., this chart shows how much were produced just in the United States).

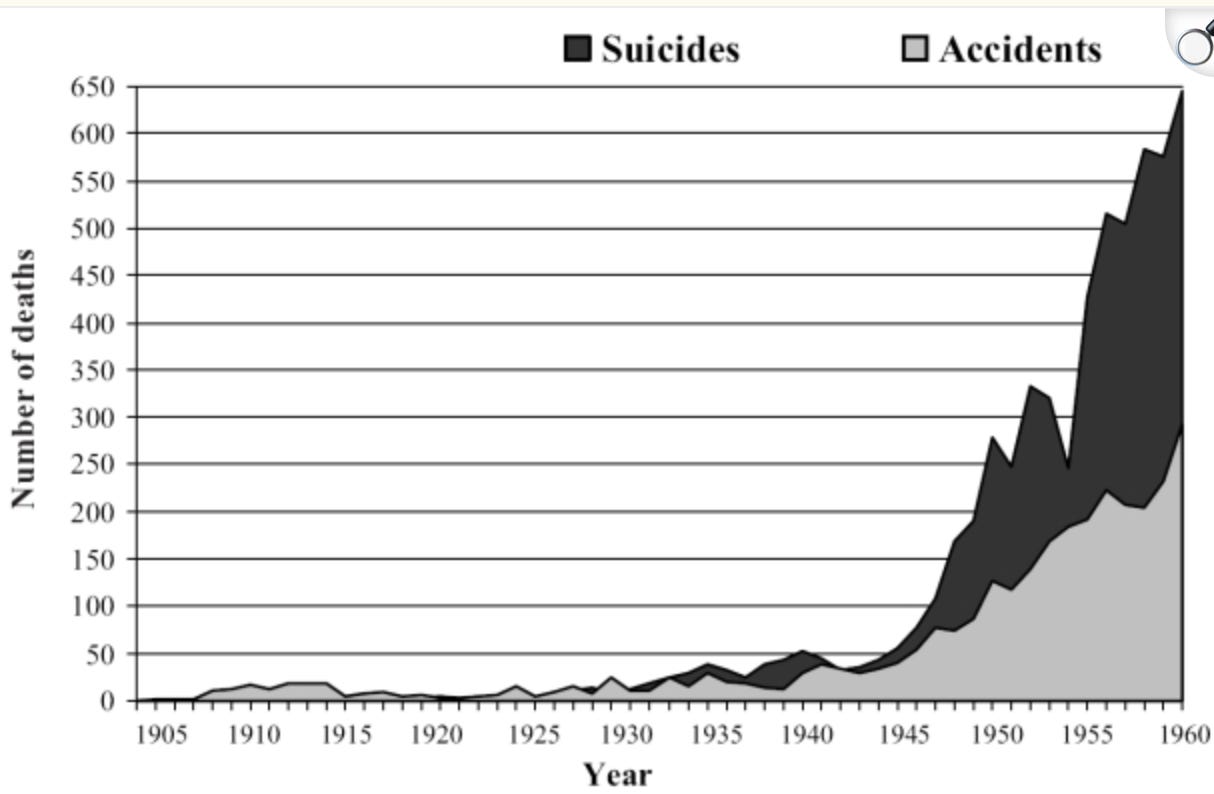

Unfortunately, from the start, it was clear the drugs had significant issues such as being highly addictive, impairing cognition or respiration, and repeatedly causing fatal overdoses (e.g., of Marilyn Monroe—arguably the most famous actress in history), so increasing concerns developed over its long-term use to manage permanent conditions like anxiety.

Within a year of the first barbiturate hitting the market, reports emerged in the medical literature of the addictive nature of barbiturates (e.g., “the Veronal habit”), but it was not until half a century later in the 1950s, that reliable evidence emerged that they were addictive. Proposals were made to have them be available by prescription only, and it took until the 1970s for laws to be introduced to treat them as a controlled substance with restricted prescribing rules. For context, in 1962, Kennedy’s commission estimated that as many as 250,000 Americans were addicted to barbiturates, while in England in 1965 it was estimated that there were 135,000 barbiturate addicts.

Note: in more recent times, other serious side effects with phenobarbital have been recognized, such as severe withdrawals when discontinued abruptly or liver damage and increased risk of certain cancers with long-term use.

When significant concerns exist about a lucrative technology, I typically find they are ignored until a viable replacement can be found. For instance, recently I discussed how the Obstetrics field routinely gave X-rays to pregnant women despite 50 years of warnings it endangered the fetus and only acknowledged those dangers once a viable alternative (prenatal ultrasounds—something which also has safety issues) became available.

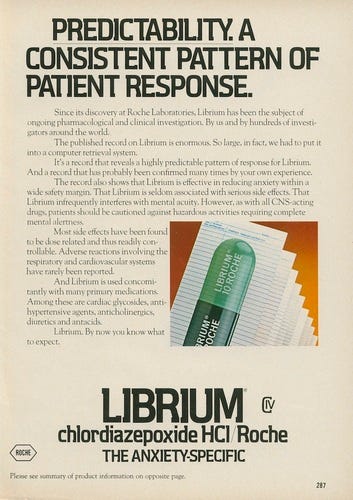

In the case of barbiturates, recognizing the immense profitability of sedative medications, many attempted to produce other viable products. As it happened, one researcher at Roche was particularly drawn to this, and spent years searching for viable alternatives even after being ordered to stop and devote his time elsewhere. Eventually, in 1956, he discovered the first benzodiazepine, and Roche quickly recognized it (Librium) would be a blockbuster (which led to Roche funding one of the largest clinical trials in history for it).

Out of the 20,000 patients Roche tested, 1,163 patients (those who did not show signs of addiction or tolerance) were then selected to be presented to the FDA. As you might expect, these dramatic results quickly won a 1960 FDA approval, and before long, the more dangerous barbiturates (which were easier to accidentally overdose on) were displaced.

Roche, in turn, claimed Librium was an effective treatment for all types of anxiety and that it could be used as a muscle relaxant, for seizures, sedation, depression, and alcohol withdrawals. As it happened in 1960, Max Hamilton developed a scale to measure depression (and another to measure anxiety), which to this day are frequently used to evaluate those disorders. Since that scale transformed anxiety into an “objective” disorder with a scientific basis, Roche immediately recognized its value and distributed it to tens of thousands of doctors so they could diagnose and then “treat” anxiety.

Likewise, Roche hired Arthur Sackler to launch an expensive campaign to promote Librium which included:

•Convincing newspapers around the country to publish friendly stories highlighting the most remarkable trial results for Librium and suggesting it was a breakthrough drug that would transform medicine (thereby bypassing existing advertising regulations).

•Placing magazines with those stories in doctor's offices nationwide (again bypassing advertising regulations).

•Aggressively targeting women’s magazines (as Sackler suspected women would be a larger market).

•Aggressively targeting doctors to both convince them Librium (unlike barbiturates) was “safe” and that anxiety (an almost unlimited market) needed to be treated.

•Specifically targeting general practitioners (as they were unlikely to recognize the dangers of Librium) rather than psychiatrists (who already had significant familiarity with the sedative medications and served a much smaller patient population).

In turn, this deceptive campaign (and the subsequent 1963 one for Valium) were remarkably successful.

Physicians wrote 1.5 million Librium prescriptions in its first month of sales. It was dispensed for alleviating anxieties and phobias, as well as illnesses then thought to have a link to stress, including high blood pressure, ulcers, acne, muscle pain, and headaches. It was not public knowledge then, but even John Kennedy—wracked by lower back pain from his wartime injury—took Librium.

In the mid-to-late 1970s, benzodiazepines topped all "most frequently prescribed" lists. By the 1980s, clinicians' earlier enthusiasm and propensity to prescribe created a new concern: the specter of abuse and dependence. As information about benzodiazepines, both raising and damning, accumulated, medical leaders and legislators began to take action. The result: individual benzodiazepines and the entire class began to appear on guidelines and in legislation giving guidance on their use.

Note: in the same way Librium was marketed as being “non-addictive,” Sackler’s descendants did the same with the synthetic opioids.

Appraising Benzodiazepines

Since it’s impossible to know all there is to a subject, we frequently are forced to make decisions based upon our pre-existing biases. Simultaneously however, it is virtually guaranteed that if you take a hardline position on any issue, you will inevitably make significant errors.

For instance, I hold a strong bias against pharmaceuticals, particularly psychiatric medications such as the SSRI antidepressants, as I routinely encounter them creating significant side effects and failing to benefit patients. Likewise, for most conditions, I know of non-pharmaceutical alternatives that are just as effective (if not more so) and do not have the same risks as pharmaceuticals. However, while I hold strong biases on this topic (especially since so many people I’m close to have been severely injured by pharmaceuticals) and rarely prescribe, I still will extensively consider the merits of pharmaceutical drugs as:

•With many drugs, while they typically are more likely to harm than help each patient, there is a subset of patients who benefit from them with minimal risk.

•In many cases (especially for less affluent patients), there are the only accessible therapy available for a condition.

•In many cases, a quick fix (e.g., a 10 minute visit and prescription) is the only thing both the doctor and patient have time for.

•Some drugs, while not ideal, have a good enough risk to benefit ratio.

•A subset of pharmaceutical drugs are extraordinarily effective for specific conditions; to my knowledge, nothing comparable to them exists in any other medical system.

Note: about 10 years ago, I spent months going through Wikipedia’s lengthy (but incomplete) list of every drug in existence, ranked them by their value, and identified 31 I felt were the “gems of pharmacology.”

All of that essentially synopsizes my attitude toward benzodiazepines as:

•In the majority of cases, I believe they cause significantly more harm than benefit.

•If they are used appropriately in the correct patients (which requires a knowledge base most prescribers do not have), their benefits outweigh their risks.

•In many cases, patients need a rapid solution for the problem they are facing (e.g., crippling anxiety) and cannot afford to go through a lengthy and holistic way to mitigate the disorder. Likewise, many doctors simply cannot provide those approaches in a 10-15 minute office visit. As such, benzodiazepines are often the only available option.

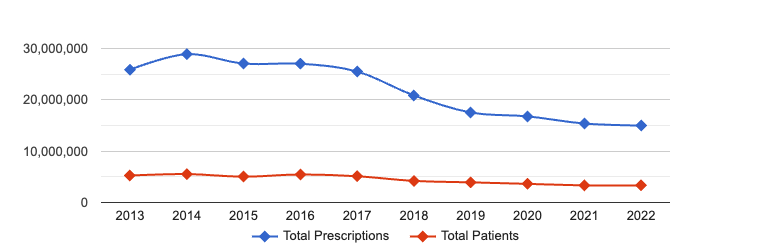

Fortunately, while benzodiazepines are still massively overprescribed, there is now an awareness of their dangers, in part because they are going off-patent (so there is no longer a strong incentive to defend them) and in part because leading voices in the alternative media are bringing awareness to it.

Risks and Benefits of Benzodiazepines

Like many of other drugs discussed thus far, benzodiazepines are typically used to:

•Treat anxiety.

•Treat insomnia.

•Relax muscles.

•Treat seizures.

•Treat mania.

•Mitigate alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

•Sedate patients.

•Reduce agitation, paranoia, and aggression (e.g., in acutely psychotic patients or those having a bad drug trip).

Note: many of the withdrawal symptoms of benzodiazepines are each of the above conditions (e.g., anxiety).

Benzodiazepines in turn, have three significant issues:

1. First, while specific benzodiazepines are sometimes appropriate treatments for some of the above conditions (e.g., specific types of anxiety, certain muscle spasms, seizures, anesthesia, alcohol withdrawals, and certain psychotic patients), they frequently will make the condition worse (e.g., anxiety) rather than better.

This is particularly important with insomnia, as benzodiazepines (and the related z-drugs like Ambien) do not put you to sleep—rather they are sedatives that sedate (shut down) restorative sleep. As such, patients who cannot sleep frequently take benzodiazepines but then suffer all the complications that are seen with chronic sleep deprivation. In fact, studies have found sleeping pill users are two to five times as likely to die as non-users, and one estimate concluded that in 2010, prescription sleeping pills “may have been associated with 320,000-507,000 excess deaths within the USA alone.”

Note: I only know of one available sleeping pill that does not block restorative sleep (along with a far more effective natural supplement the FDA waged an unconscionable war against to keep off the market). That said, when individuals have been awake for a prolonged period (e.g., due to amphetamines), benzodiazepines can often cause them to fall into a deep sleep which can be nearly a day long (far exceeding the duration of the benzodiazepine) and be fully recovered when they wake up.

2. Second, they frequently create a variety of severe side effects such as:

•Sedation, drowsiness, muscle weakness, fatigue, and loss of motor coordination (e.g., a large study found long-acting benzodiazepines increase the risk of car accidents by 45%, while another meta-analysis found a far larger increase, and a third study determined benzodiazepines in the first three years of use created impairment greater than what alcohol sufficient to cause a DUI would cause).

Note: commercial drivers are prohibited from taking benzodiazepines.

•Dizziness or Lightheadedness (e.g., a study of 2,510 nursing home residents found they increased the risk of falls by 44%).

•Confusion, disorientation, and impairment of cognitive functioning, processing speed, short term memory, or forming new memories (e.g., one study found that about 20.7% of long-term benzodiazepine users exhibited cognitive impairment across various domains, including processing speed, sustained attention, and episodic memory, meta-analyses have shown significant deficits in cognitive functions such as working memory, processing speed, and visuospatial abilities among long-term users, and a meta analysis (along with a case-control study) found long-term use increased the risk of dementia by 51%). Some of these effects are likely due to benzodiazepines blocking restorative sleep, so for this reason, we frequently strongly caution students who “need them to reduce studying anxiety” to avoid using benzodiazepines while studying (as it is highly counterproductive to learning)—in contrast, many highly effective approaches exist to enhance learning.

Note: many benzodiazepine users I’ve spoken to have shared that their perception of reality changes (in a way akin to going through life in a “flow state” as you feel great in the moment and your internal chatter silences), that time flashes by so fast” and that it is often quite difficult for them to remember what had happened while they were using these drugs (known as anterograde amnesia). For those interested in learning more, this article discusses the extensive memory impairments created by benzodiazepines (e.g., in 1972, it was known that regular diazepam doses reduced recognition memory in 90% of women).

•Respiratory depression, which can be lethal, especially when combined with other respiratory depressants.

Note: one benzodiazepine (midazolam) is frequently used for lethal injections and medically assisted dying, and during COVID-19, its use in association with morphine (another respiratory suppressant) was associated with a large number of nursing home deaths in England and Ireland.

•Causing many of the conditions they are supposed to treat (e.g., agitation and aggression), especially after the drugs are stopped. For example:

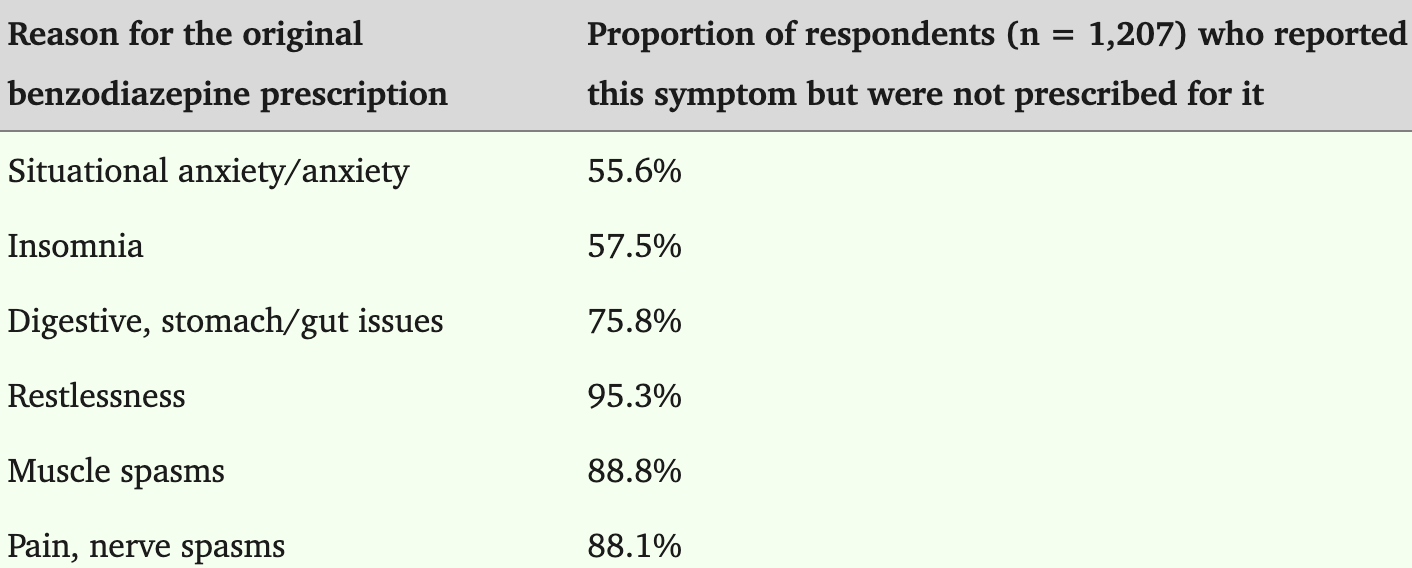

Additionally, many of these symptoms often last long after the benzodiazepine is discontinued.

•Causing visual disturbances such as double vision (e.g., one study found 63.3% of long-term benzodiazepine users reported symptoms such as blurred vision and difficulty reading).

3. Third, certain groups are particularly at risk of these complications but nonetheless frequently take these drugs. For instance, nearly 1.9% of pregnant women worldwide report using benzodiazepines despite risks of complications like early delivery, low birth weight, congenital malformations, floppy infant syndrome, and withdrawal symptoms (e.g., one study found a 41% increased risk of premature birth, another found a 69% increase in miscarriages, while another found a 145% increase in C-sections, a 241% increase in low birthweights, and a 185% increase in newborns requiring ventilatory support).

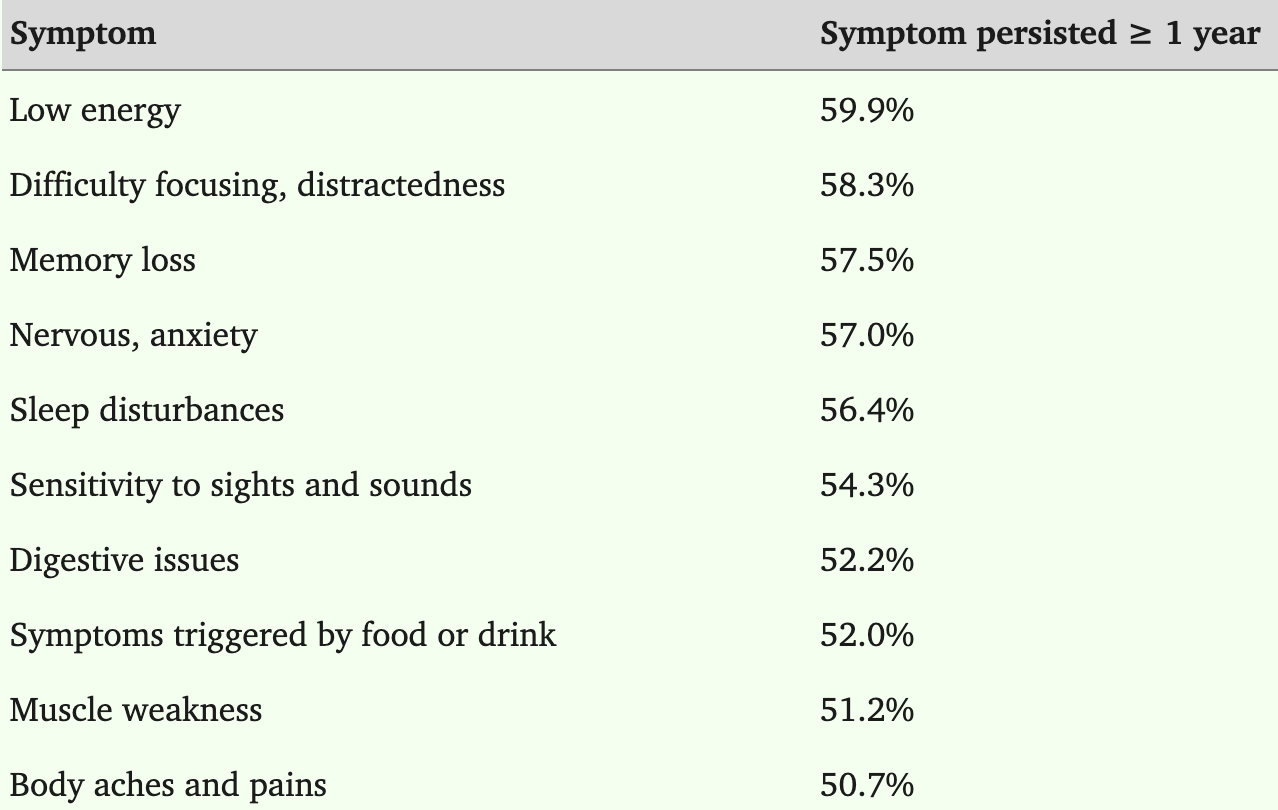

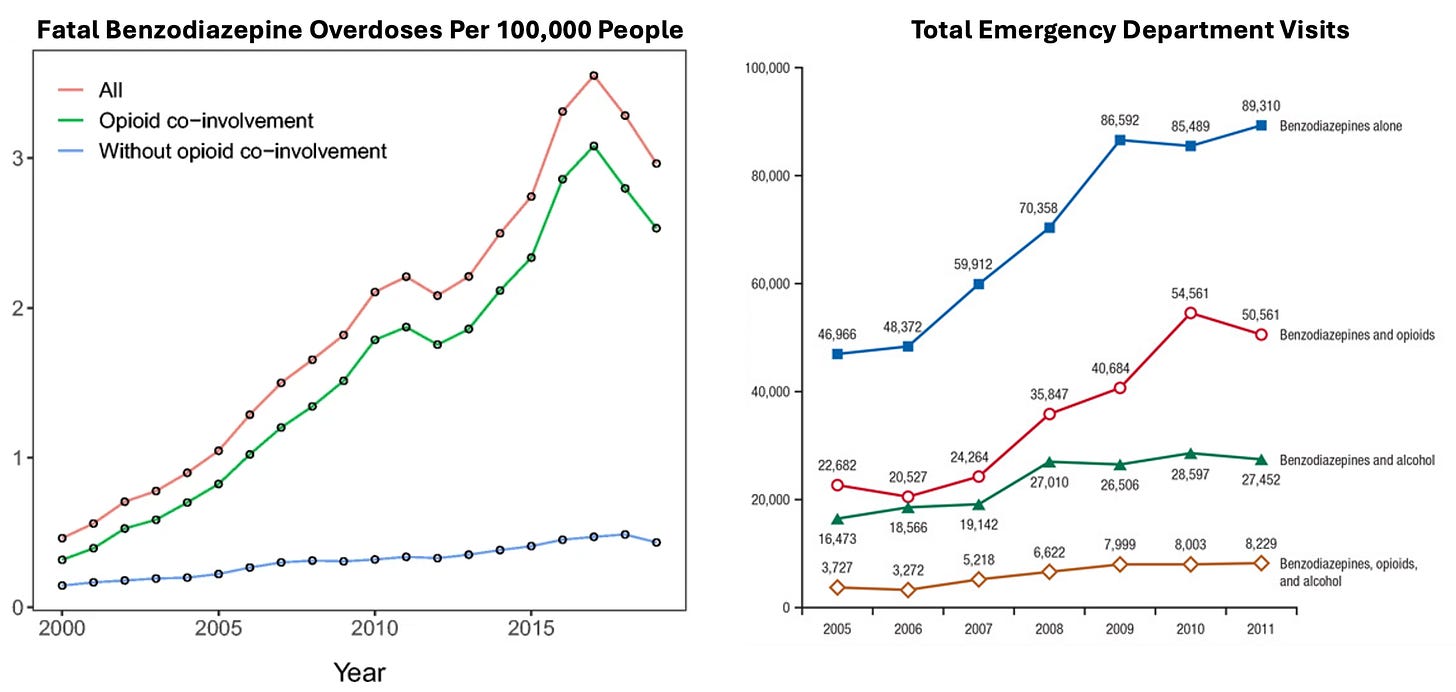

Likewise, the elderly are particularly vulnerable to cognitive impairment and falls benzodiazepines cause—particularly since they often have impaired metabolism of the drugs (to the point in 2012 the American Geriatrics Society recommended against giving them to older patients), yet benzodiazepine use steadily increases with age.

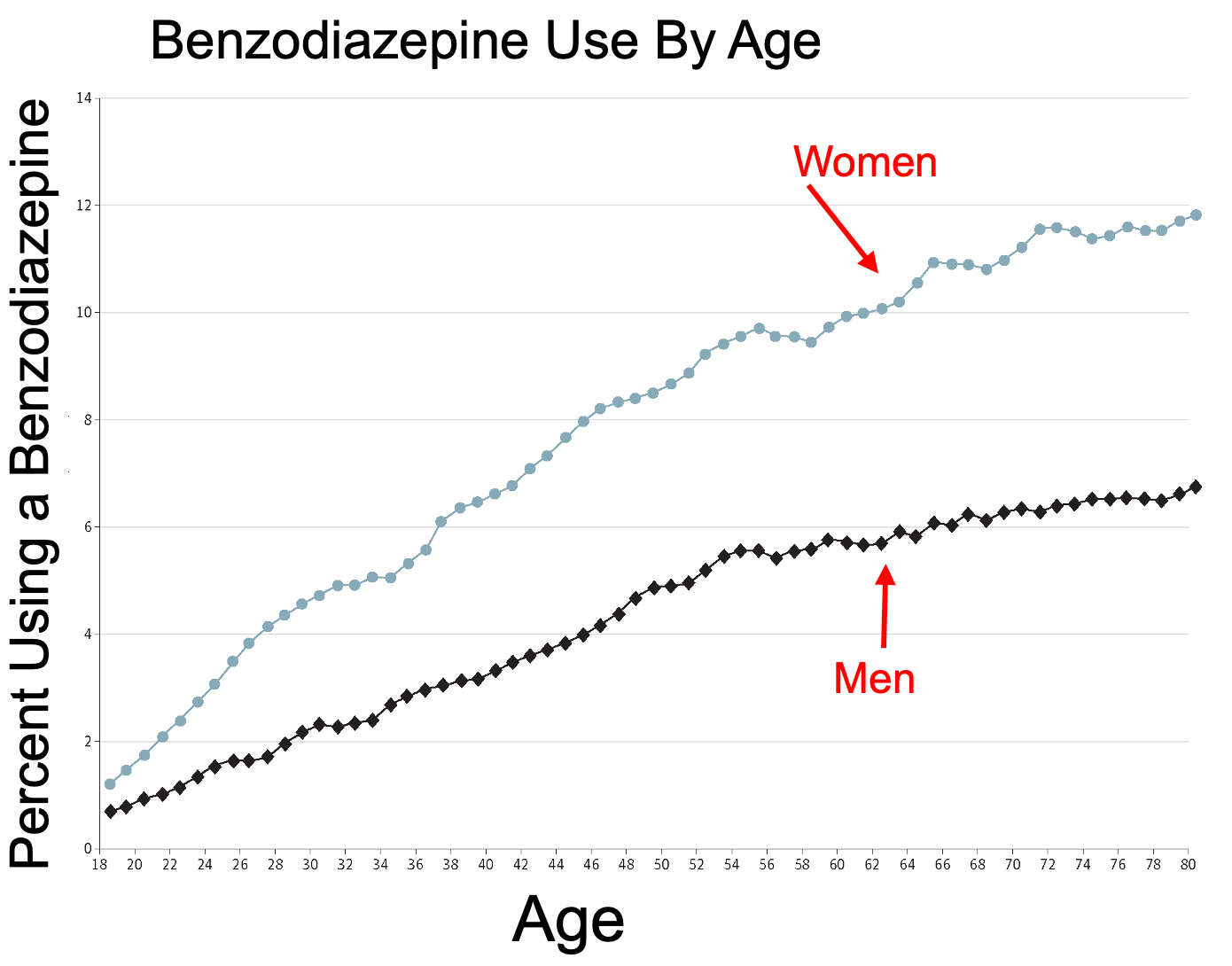

4. Finally, they have a high risk of overdosing—which is particularly problematic since they are also highly addictive, and sadly, in tandem with increasing benzodiazepine use, this cycle keeps on increasing. For example, from 2004 to 2011, emergency room visits involving benzodiazepine misuse rose by 149% (from 11.0 to 34.2 per 100,000 people) and in 2021, there were around 12,499 deaths involving benzodiazepine overdoses, up from 1,135 deaths in 1999 (a 917% increase over 22 years).

Benzodiazepine Addiction

As benzodiazepines gradually downregulate the GABA system, once they wear off, the symptoms the drugs addressed not only come back, but often in a manner more severe than they had been prior to initiating the benzodiazepines. Many of these symptoms mirror what is seen in alcohol withdrawals and illustrate why benzodiazepines are so challenging to quit.

Common Symptoms: Anxiety, Insomnia, Irritability, Tremors, Muscle Stiffness and Pain, Sweating, Nausea and Vomiting, Headaches, Panic Attacks, Dizziness, Heart Palpitations

Psychological Symptoms: Confusion, Memory Problems, Depression, Hallucinations, Delusions, Paranoia

Sensory Symptoms: Tinnitus, Burning Sensations, Derealization/Depersonalization

Physical Symptoms: Seizures, Muscle Twitches, Loss of Appetite and Weight Loss, Diarrhea

Other Symptoms: Dry Mouth and Metallic Taste, Difficulty Swallowing, Flushing and Skin Rashes

Note: typically anxiety, insomnia, irritability, and muscle stiffness are the earliest symptoms to occur (e.g., after 1-4 days), while at weeks 1-2, the most severe symptoms occur. Unfortunately, for 10-15% of users, post-acute withdrawal symptoms (PAWS) such as anxiety, insomnia, depression, cognitive impairment, and mood swings can last for several months to years (typically around 1-2 years but in some cases 5-10 years).

Tragically, existing estimates find roughly half of benzodiazepine users experience withdrawal symptoms when they either stop the drug or simply decrease the dose, while 20-30% experience rebound symptoms (where the symptom is worse than it was prior to the benzodiazepine) and around 10% experience withdrawals that are “quite distressing (e.g., they are 40% more likely to become suicidal). Sometimes withdrawals can be quite severe (e.g., seizures occurring—which without treatment have the potential to be fatal), and when tracked, those who discontinued tended to be 60% more likely to die in the next year (amounting to 2.1-2.4% of them dying who otherwise would not have).

Note: many benzodiazepine users obtain benzodiazepines off the black market (e.g., an extensive survey determined 5.3 million Americans “misuse” benzodiazepine either by using a dose differing from what was prescribed [26.1%] or simply by obtaining it illegally [73.9%]). As such, there is a large pool of people who are at a much greater risk for these withdrawals (e.g., since they can’t ensure a constant supply) who may then either experience significant medical complications from them or turn to an addict lifestyle so they can somehow obtain their next fix to prevent the inevitable withdrawals. Typically, young adults misuse benzodiazepines (either recreationally or to self-medicate), whereas older adults tend to be harmed by these drugs because they are on long-term benzodiazepine prescriptions.

Remarkably, all of this has been well-known for decades. Consider for instance, this 1979 Senate hearing covered by the New York Times, where Senator Kennedy highlighted that Valium and Librium had produced “a nightmare of dependence” for many people.

“Classically today, if a woman walks into her doctor's office and says, ‘I'm nervous, my husband drinks too much,’ the doctor will automatically give her a tranquilizer,” said the Navy psychiatrist, whose patients have included Billy Carter, the President's brother; Betty Ford, wife of the former President, and Senator Herman E. Talmadge, Democrat of Georgia.

More than 44.6 million Valium prescriptions were filled last year. Many doctors who write such prescriptions do not realize the dangers of their patients becoming addicted to Valium, Librium, and other mild tranquilizers, Dr. Pursch said.

Asked by Senator Edward M. Kennedy, the subcommittee chairman, whether Valium alone was a problem in American society, Dr. Pursch replied that he had seen people become addicted to the tranquilizer in only six weeks.

“None of these drugs solve our problems,” Dr. Pursch said. “They make people feel better because they make you feel dull and insensitive. But they don't solve anything.”

However, Robert B. Clark, president of Hoffmann‐La Roche Inc., the manufacturer of Valium, maintained that it was a safe and effective drug when properly used. He said that addiction was “extremely rare” at recommended dosage levels, and that Valium did not appear to be more addictive than any other mild tranquilizer.

Mr. Clark said that the vast majority of patients on Valium used it for only a short time, followed their doctors’ instructions, and had no problem with the drug. But he [in 1979] said his company would begin a program to make certain that information on the risks and benefits of Valium was included in each container for the patient to read.

Despite this, the use of benzodiazepines has continued to increase (e.g., in 1996 4.1% of adults had a benzodiazepine prescription, whereas in 2018, 12.6% reported benzodiazepine use in the past year). In tandem, ER admissions, hospitalizations, and lethal overdoses for these drugs have continually increased, particularly when given concurrently with opioids (as both cause respiratory depression and hence increase the odds of fatal respiratory arrest).

Note: other sedating drugs that decrease respiration can also be problematic with benzodiazepines (e.g., antihistamines like Benadryl), so it is essential to be mindful of what other drugs are taken concurrently.

In turn, many high-profile benzodiazepine deaths have happened (e.g., Michael Jackson, Heath Ledger, Tom Petty, Prince).

Note: women are almost twice as likely as men to be prescribed benzodiazepines.

Insufficient Treatment Time

One of the greatest problems in psychiatric care is that typically (unless there is a clear organic cause of the illness such as an undiagnosed chronic infection like Lyme or a micronutrient deficiency), the most therapeutic thing a psychiatrist can do is to be fully present to their patient (e.g., viewing the interaction as a sacred event) and spending a prolonged period of time with them—to the point that psychiatrists who make the “wrong” medical choices for their patients but spend time with them often get better outcomes than psychiatrists with rushed visits who don’t make those errors.

Unfortunately, despite extensive visits characterizing the best psychiatrists in practice (good results normally require visits roughly an hour due to the patient’s mind needing time to expand shift and morph at its own pace during the visit, although visits can be a bit shorter on repeat visits if not that much is being done), it’s very rare this actually happens. That’s because psychiatrists (and general practitioners—who frequently treat psychiatric cases) are typically allotted 15 minute visits by the insurance-based healthcare system where a significant portion of their mental space during a visit has to be focused on something besides being fully present to the patient. Likewise, my colleagues who spent more than 15 minutes with patients (because they feel it is important) frequently get significant administrative pushback both for keeping the clinic open late and having much lower patient volumes (as they simply cannot see as many people at a time).

Note: much of medicine revolves around finding ways to use external technology, support staff, (and likely AI in the near future) to outsource many of a doctor’s tasks. This does not work in psychiatry (unless the practice revolves solely around prescribing medications) as many of its diagnoses can only emerge from direct interaction with the patient and the psychiatrist’s presence is the key therapeutic ingredient, so psychiatry is effectively stuck in the position of the medical industry trying to scale it, but it simply not scaling well (as once that is attempted, much of what actually works in it becomes lost).

In turn, a good case can be made that many of the issues which emerge with psychiatric medications result from this limited therapeutic interaction. For example:

•Unless a patient gets to know their physician well, they are unlikely to report important side effects like SSRI sexual dysfunction (which affects the majority of SSRI users) which indicates the dose of the medication is not appropriate.

•Medications will be used in lieu of the more time consuming therapies a patient needs.

•Medications will frequently be incorrectly prescribed and the patient will not be given comprehensive warnings about the risks of medication and what to look out for (as there simply isn’t time to do it).

Unfortunately, the only real solution to this, seeing a cash-pay psychiatrist (not covered by insurance) who ideally has an integrative background, is not affordable for most patients, as depending on who you see and the area you live in, this normally costs between 250-500 an hour (which I would argue is a good investment given how costly poorly prescribed psychiatric medications can become), particularly since those psychiatrists normally have to spend a significant amount of time outside of the visit preparing for the patient.

Note: a few of my colleagues (who charge significantly more) treat VIP psychiatry patients (e.g., celebrities). What I’ve found remarkable from talking to these people is that while I often despise the politics of this social class, on an individual basis (and in private with their psychiatrist), those VIPs are often fairly nice people who suffer from all the same emotional issues and stressors regular members of society experience (along with having to regularly deal with the paparazzi—which is frequently immensely stressful).

Inappropriate Benzodiazepine Prescribing

In reviewing more benzodiazepine addiction cases than I can count, a few issues commonly recur—many of which I feel ultimately result from prescribing doctors simply having too little time with their patients.

First, benzodiazepines (and SSRIs) tend to work much better for anxious patients who have first received psychotherapy (typically cognitive behavioral therapy—which as this systematic review shows is a highly effective treatment for anxiety).

Unfortunately, since therapy is resource intensive, this often is not done. In an ideal world, all patients with anxiety would first receive psychotherapy appropriate for their type of anxiety, then if that does not get them well, start them on an appropriate medication (which provided psychotherapy has already been done for, they are likely to have a far more rapid response to that if the medication is given without prior psychotherapy), and then gradually reduce the medication to the minimal dose the patient needs (or completely withdraw it).

Second, patients are not warned by their doctors as to how addictive the benzodiazepines can be (and had they known many said they would have never started them).

Third, many do not know that using benzodiazepines for as little as 3-6 weeks can create a physical dependence that can give way to a permanent addiction.

Fourth, many do not know or appreciate how difficult it is to wean off benzodiazepines, as the process often takes years of daily methodical work (and if the process is done even a little bit too quickly, it can create a backlash which makes it much harder to quit them).

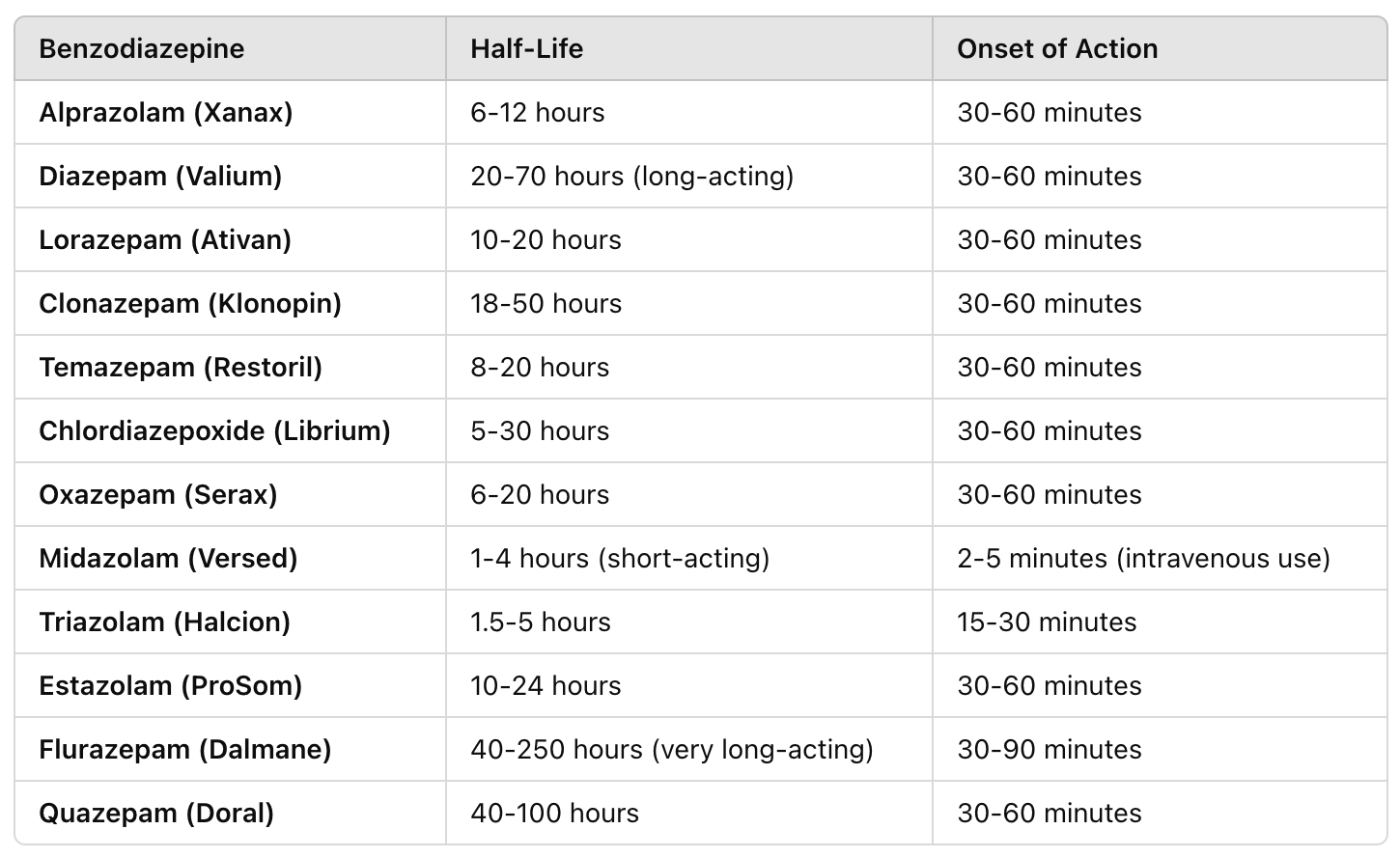

Fifth, many do not appreciate that certain benzodiazepines have a much higher risk of addiction, particularly those with a short half-life.

The short acting benzodiazepines tend to have the greatest risk for addiction, particularly Xanax due to the fact it concurrently creates a euphoria when it is taken (and a depression once it wears off).

Note: individuals commonly mistake the euphoric effect of a drug with its therapeutic effect. As such, when taking psychiatric medications, the goal of a patient should be to “feel fine” not to “feel good.”

Unfortunately, the issues with Xanax are still not sufficiently recognized by the medical field and it remains one of the most commonly prescribed benzodiazepines.

For context, Xanax used a similar playbook to Librium, with its developer (Upjohn which was later acquired by Pfizer) popularizing “panic disorders” (to the point they came to be known as the Upjohn illness) marketing Xanax as the treatment for this “epidemic” sweeping the nation, and before long creating a blockbuster drug that was one of the most prescribed medications in psychiatry.

Note: the other benzodiazepine that frequently creates issues is Valium as its metabolite is also physiologically active, so over time, it will build up inside the body (which while typically problematic, can be quite helpful in epilepsy since there is a need to constantly prevent the seizures).

Sixth, because benzodiazepines frequently build up tolerances, prescribers often use much higher doses than are appropriate and then increase them as the patient develops a tolerance to them. Conversely, the people I know who have the best results with benzodiazepines use very low doses (e.g., they start with one-half or one-quarter of the recommended dose, monitor the patient’s response to it, and only raise it a bit if needed).

Finally, because patients can be so sensitive to benzodiazepine withdrawals, small changes in the doses can often create significant problems. This frequently arises when generic formulations of the drugs are made (as significant quality control issues exist with many generics produced overseas, and the pharmacologic action of generic benzodiazepines can be surprisingly inconsistent). As such, my colleagues periodically will have patients who were changed to a different brand of an existing prescription that developed significant complications as the two pills were not equivalent.

Note: a recent problematic example of this occurred when a generic version of Adderall (Zenzedi) was recalled on January 24, 2024 due to a mix-up where carbinoxamine maleate, an antihistamine, was found in the packaging instead of the intended medication. For those wishing to know more about the problems with generics, it is extensively detailed in this book and this article.

Somewhat similarly, I have heard a few stories of similar issues occurring with psychiatric patients on Ozempic, as Ozempic slows gastrointestinal transit and hence delays absorption of medications (which with certain psychiatric medications can then trigger withdrawals) and in patients with Crohn’s Disease (which also impairs gastrointestinal absorption.

In short, benzodiazepines can be very helpful if they are used for a type of anxiety that responds to their action, and they are appropriately used for a short period of time. Unfortunately, they instead tend to be given for a broad swathe of anxieties and then continued indefinitely, at which point their harms greatly outweigh any benefit they can provide. In many ways, benzodiazepines could be analogized to the “nuclear option” for anxiety. Still, providers are far too quick to use them rather than first attempting to consider the far safer options that are available.

Note: due to how prevalent benzodiazepine addiction is, a large industry has emerged to help detoxify individuals with dependencies. In some cases, these centers (which can sometimes cost $1000.00 per day) can be helpful (e.g., if the addiction is strong enough that the individual lacks the control to stop on their own and does not have a robust support system in place to help them), but in other cases can often be quite harmful (e.g., we have seen bad outcomes with the rapid detoxification protocols some places offer). Generally speaking, I believe a slow home tapering program (done in collaboration with a supportive psychiatrist) is the best way to approach the problem.

Overlapping Syndromes

A major challenge in medical diagnosis is that the same disease can create different symptoms in different patients, while completely different diseases can present with fairly similar symptoms. Because of this, it is typically much easier (and profitable) to give therapies that are directed at the symptomatic expressions of each disease rather than taking the time to determine exactly what is causing the illness to trigger and giving the remedy that specifically addresses it.

As such, one of the most common reasons individuals seek out the (often costly) realm of non-insurance covered integrative medicine is due to the fact that the symptomatic management conventional care offers leads to unacceptable outcomes (e.g., many debilitating symptoms remaining, costly and harmful “treatments” needing to be done indefinitely, or the illness progressing).

In a previous article on the depression industry, I highlighted a major problem with the condition—rather than there being one type of depression, numerous different things can cause it. This is often quite consequential, as while some types of depression respond well to SSRI antidepressants, others do not, and some become significantly worse with antidepressant therapy. As such, I believe it is immensely inappropriate to quickly diagnose someone with depression and then prescribe an antidepressant—which unfortunately is what frequently happens, particularly in 10 minute primary care visits.

A similar issue exists with anxiety as:

•Different types of anxiety exist that respond differently to psychiatric medications.

•The underlying causes of anxiety are poorly understood.

Types of Anxiety

One of the things I have long been fascinated with in medicine is how many different models can be used to describe a disease process. In turn, there are a few different ways to look at anxiety, the first of which are the common psychiatric diagnoses used to classify it, which while accurate and useful, typically are not at the forefront of my mind when evaluating it. They are as follows:

•Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)—this is characterized by excessive, uncontrollable worry about a wide range of topics, often with physical symptoms like muscle tension or restlessness, and affects about 3.1% of the U.S. population, with a higher prevalence in women. GAD (and anxiety in general) responds to best cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Conversely, if GAD is treated with a benzodiazepine, while there can be an initial positive response, the disorder will often worsen and need progressively increasing benzodiazepine doses. As such, it is extremely important to avoid benzodiazepines here.

Note: GAD is often described as having anxiety that is grossly disproportional to the magnitude of the stressor which triggers it (e.g., being a “worrywart”) and in most cases, these individuals have an underlying stressor in their life they are not fully conscious of which is a root cause of their anxiety. Since patients often have poor insight into their underlying issue, therapies which can identify the stressor (e.g., CBT) are often very helpful for GAD.

•Panic disorders—in the last year, roughly 2-3% of Americans experienced sudden unexpected and recurrent panic attacks (e.g., heart palpitations, sweating, dizziness, chest pain, shortness of breath, and a fear of losing control or dying), frequently describing the process as though there is a “faulty trip wire in the brain” which sets off immense anxiety attacks that “just seem to come out of nowhere.” Psychotherapy is often very helpful here, as it can frequently identify what the actual trigger for someone’s panic attacks are (as they often are not consciously aware of it) and typically, panic disorders benefit from some combination of ERP and CBT therapy. ERP (Exposure and Response Prevention) for context, is a therapy where an individual is exposed to a light version of the panic trigger (e.g., imagining it or a picture of it), instructed to relax, and then once they can, are gradually exposed to more intense exposures that more closely approximate the trigger (e.g., a hose if they have a fear of snakes) until the trigger can be tolerated.

Note: individuals with panic disorders will often self-medicate with alcohol or illicitly acquired benzodiazepines.

When used appropriately, benzodiazepines can be very helpful for panic disorders, particularly since panic attacks can cause a variety of Pavlovian associations, which can gradually cause a variety of other previously benign stimuli (that were also present at the time of the panic attack) to become panic triggers as well. Specifically, in many cases (like migraines), panic attacks will be preceded by a prodrome (e.g., the face getting hot, the nose getting itchy, or too much spit in the mouth). If panic attacks have prodromes, benzodiazepines are very useful as they can be taken during that period before the panic attack. In contrast, if prodromes do not occur, benzodiazepines have minimal value. Likewise, if the panic attacks are brief, benzodiazepines typically have minimal value, whereas if they persist for hours, benzodiazepines are helpful.

Note: if individuals instantaneously feel their panic attack go away following a benzodiazepine, they most likely are having a conditioned response to the drug once swallowed, as they normally take at least 30 minutes to onset.

•Specific phobias—roughly 7-9% of people at some point in their life will have an irrational fear of a specific object, situation, or activity, such as heights, spiders, or flying, and experience panic symptoms when exposed to it. Like panic disorders, this condition responds to appropriate benzodiazepine use (e.g., it is given prior to a planned and necessary exposure to the phobia that will last roughly as long as the expected duration of the exposure) and ERP therapy.

•Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD)—individuals with social phobias (which 7-13% of people will experience at some point in their lives) have an intense fear of being judged or embarrassed in social situations, frequently experience blushing, sweating, or trembling in those situations and often avoid public places or interactions. This condition also responds to ERP therapy, and we find when medications are used, short low dose beta-blockers (rather than the habit forming benzodiazepines) are typically ideal to use.

Note: for patients with SAD, it is important to not have periods of prolonged isolation (as this makes you much more sensitive to social phobias). In turn, our patients with SAD often had significant difficulties after the COVID lockdowns ended.

•Agoraphobia—about 1-2% of people have a phobia of being in places or situations where escape could be difficult (e.g., a crowded place) if anxiety or panic symptoms were to emerge at the same time, they were there (essentially anxiety about anxiety). This also responds well to ERP therapy.

•Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—OCD involves unwanted, intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or rituals (compulsions) performed to reduce the anxiety caused by the obsessions. This form of anxiety affects 1-2% of the population, and does not respond to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or benzodiazepines (at best they can reduce OCD induced panic but do not address the underlying anxiety), but does respond to ERP therapy.

Note: while I avoid SSRIs, my psychiatrist colleagues, who are relatively conservative with medications, will typically address this form of OCD with SSRIs.

•Post Traumatic Stress Disorder—PTSD is another frequent cause of anxiety and affects 3-6% of the population (and sometimes results in self-medication, particularly to prevent flashbacks).

•Adjustment disorder—when an individual has a large life-changing stressor (e.g., the loss of a job, a severe illness, or the death of a loved one) they can have a great deal of difficulty being able to function. In many cases, benzodiazepines are given to mitigate those symptoms (which frequently leads to significant issues as they transition to long-term benzodiazepine use). Generally, this responds best to CBT and supportive social work, but in patients who do not want CBT, some of my colleagues use low doses of SSRIs for 6-12 months.

•Stressful life syndrome—many individuals are stuck in challenging life situations (e.g., an unhealthy relationship, being close to poverty, having a job they hate) which provoke depression and anxiety (e.g., their boss molests them at work but they cannot afford to leave the job or legally fight the abuse). In these instances, psychiatric care is often sought to help the individual handle the understandable distress they feel from having to handle a bleak and challenging situation each day. In turn, we believe it’s critical to always emphasize the actual “treatment” is to leave the situation—but in practice, many patients either won’t or can’t (e.g., because we are in a challenging economy and a social safety net is often not there for those who need it). As such, when good social support services (e.g., good social workers) aren’t available (which often varies greatly by city and state) we often try to focus on giving patients the tools to find meaning in their lives instead.

Note: many physicians try to “treat” these situations with psychiatric medications (as they believe they have a duty to relieve suffering). In most cases, psychiatric medications cannot improve distress that has a legitimate external cause, and hence frequently “work poorly” because they are given for situations where they can do very little to begin with.

Finally, other rarer forms of anxiety, such as substance-induced anxiety disorder also exist (but are beyond the scope of this article).

Note: it can sometimes initially be difficult to determine what form of anxiety someone has either because they are concealing it or are in denial over the root cause of it or because they have multiple forms existing concurrently. As such, I believe it is important for patients to understand the types of anxiety so they can avoid being misdiagnosed and given the wrong treatment.

Causes of Anxiety

With some types of anxiety (e.g., PTSD anxiety), the cause is fairly straightforward. However, it is far more ambiguous with many others within the existing psychiatric framework.

Mental Causes of Anxiety

One of the most common processes that underlie anxiety (particularly GAD) is people’s minds wandering into the future, them coming up with a negative one (e.g., a future where things go awry). Then various things within the individual react to the negative future and catalyze the physiologic reactions to anxiety.

I believe this process is a result of:

•Our society teaching individuals the solution to the dilemmas we face is to overthink them (e.g., GAD individuals with high IQs tend to have a greater degree of worry) rather than encouraging the development of emotional intelligence (which I suspect is due to emotional intelligence increasing one’s immunity to marketing).

•Most of the marketing we are exposed to teaches us to focus on attaining or losing expectations in the future rather than being content with the present.

•Much of the mass media “hooks” its customers by bombarding them with shocking content and the fear of something abysmal happening in the future that they can never stop worrying about.

•Social media causing individuals to negatively compare themselves to the glamorized lives of others and upsetting context being juxtaposed with ads because individuals in a distressed state are more likely to click through on them.

Note: we noticed this was primarily an issue with Meta (e.g., Facebook, and then Instagram once Facebook bought it) as their algorithm prioritizes this approach. For this reason, we often advise anxious patients to avoiding the news and social media, and particularly, to avoid comparing themselves to people presenting a glamorized (and likely inaccurate) rendition of their life online.

•We live very disconnected (mental) lives that put us in our heads rather than into the reality around us.

•Being habituated to have a fear rather than acceptance of the unknown (and believing we can address that fear by overthinking the unknown). This point is particularly important as we find many cases of anxiety ultimately boil down to a fear of the unknown.

•The media has sold the message to America that we “should never feel bad” (both to sell psychiatric medications and because it makes us more susceptible to emotional marketing). Because of this, the default response individuals will have to an anxiety producing situation is to try to suppress the anxiety (e.g., with a pill or product). Many hence never develop the emotional coping mechanisms necessary to handle stressful situations (e.g., we know numerous chronic marijuana users who would smoke throughout childhood whenever they had an emotional obstacle and then completely lost the ability to deal with emotional adversity they encountered later in life).

At the same time however, if you simply tell people to “stop overthinking things” that normally doesn’t work, so the cognitive aspect of anxiety is only one part of the picture.

Note: to some extent, anxiety is contagious (e.g., you can periodically observe panic rapidly overtake a crowd,) so for this reason, if you are struggling with anxiety, it is often quite helpful to distance yourself from the anxious people in your life. Likewise, treating a parent’s anxiety (e.g., with CBT) has repeatedly been found to reduce anxiety in their children.

•Lastly, other co-existent issues (that are frequently missed during evaluation) such as speech disorders or trauma will also trigger chronic anxiety.

Physiologic Causes of Anxiety.

While a variety of issues within the body can give rise to anxiety, a few common ones repeatedly emerge.

•Human physiology relies upon a balance between the sympathetic (fight or flight) nervous system and the parasympathetic (rest and relax) branches of the autonomic nervous system. When these become imbalanced (too much sympathetic activity or too little parasympathetic activity), individuals become prone to anxiety (e.g., panic disorders). In turn, I’ve lost count of how many people I’ve met who had rapid and dramatic improvements in their anxiety once the dysfunctional half of their autonomic nervous system was addressed (e.g., panic disorders are often characterized by excessive sympathetic activity). I feel it is immensely unfortunate causes of autonomic dysfunction are so commonly ignored.

Note: some of the common treatments for anxiety are pills that block the sympathetic nervous system.

•When your blood sugar becomes too low, this will trigger a sympathetic response that both raises blood sugar, but also creates many of the classic signs of sympathetic activation (e.g., a racing heart rate, sweating, anxiety). In a subset of people, they cannot effectively maintain their blood sugar levels with a typical diet, and hence frequently experience “reactive hypoglycemia” (or subacute forms with difficulty focusing and concentrating). Oddly, while this condition is quite common, it is rarely recognized and often erroneously treated with benzodiazepines rather than a healthier diet.

•When the normal function of the central nervous system gets disrupted, anxiety can often follow. One of the most interesting illustrations of this we’ve repeatedly observed is that a subset of anxiety prone individuals significantly improve in Wifi-free environments, and in many cases they’ve shared that “their spines feel better” (suggesting something changed within the spinal cord).

Note: we’ve also noticed that disabling Wifi routers at night can help with anxiety and that there were temporary spikes in it at the time a significant change occurred in the ambient EMF exposure (e.g., during the 5G rollout) which people then adapted to and it disappeared.

•Artificial lights (particularly blue light) irritate the nervous system and can cause anxiety. Likewise, circadian disruptions (which are caused by blue light) and sleep disruption often cause anxiety (which is unfortunate because anxiety also causes insomnia). Conversely, simple things like going outside fist thing in the morning and having sunlight contact your face and eyes (e.g., while having a walk) can often do wonders for psychiatric conditions like anxiety and depression.

•I frequently find individuals with vaccine injuries (particularly COVID vaccine injuries) develop anxiety. Presently I believe this is either due to heart damage (e.g., irregular heart rates can trigger anxiety), impaired blood flow to the brain (or drainage from the brain), or vaccine induced neurological damage within the brain.

•Thyroid disorders and various types of heart disease can sometimes trigger anxiety (as can other rarer conditions like paraneoplastic syndromes where tumors release signaling molecules).

Metabolic Causes of Anxiety

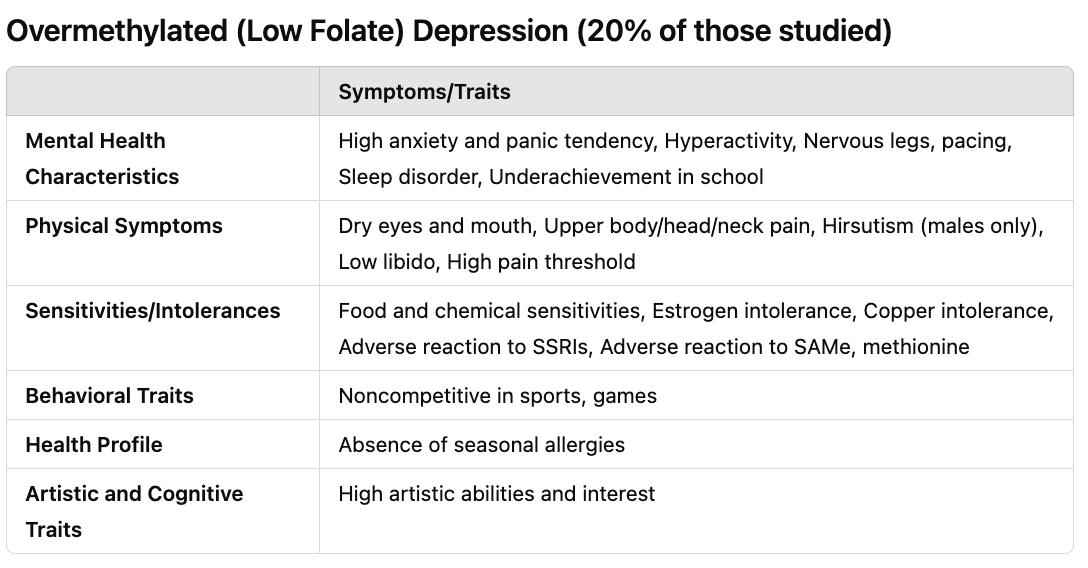

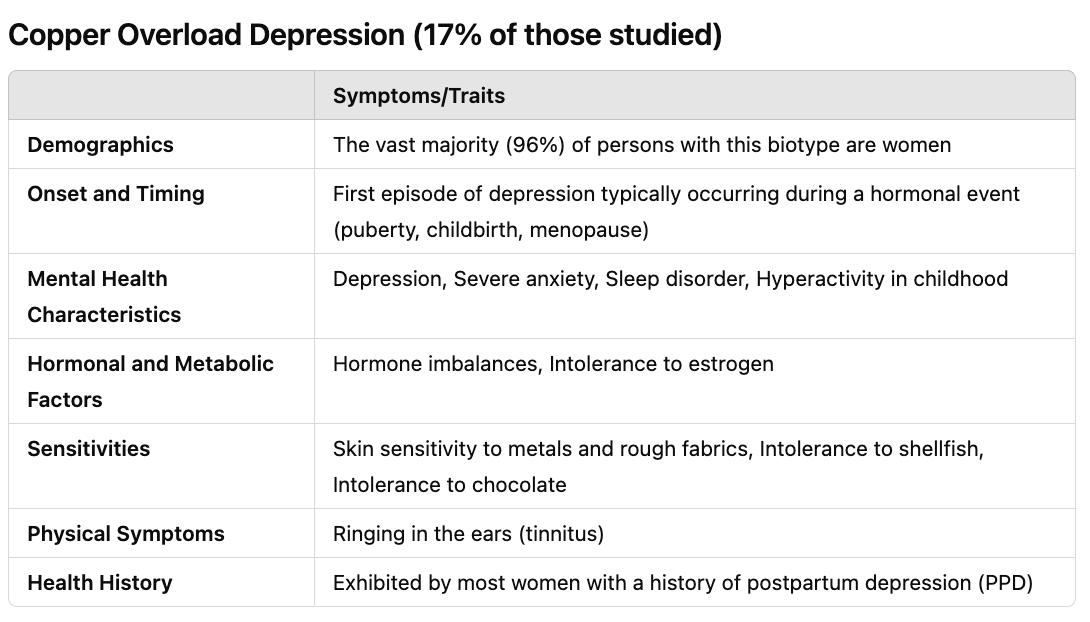

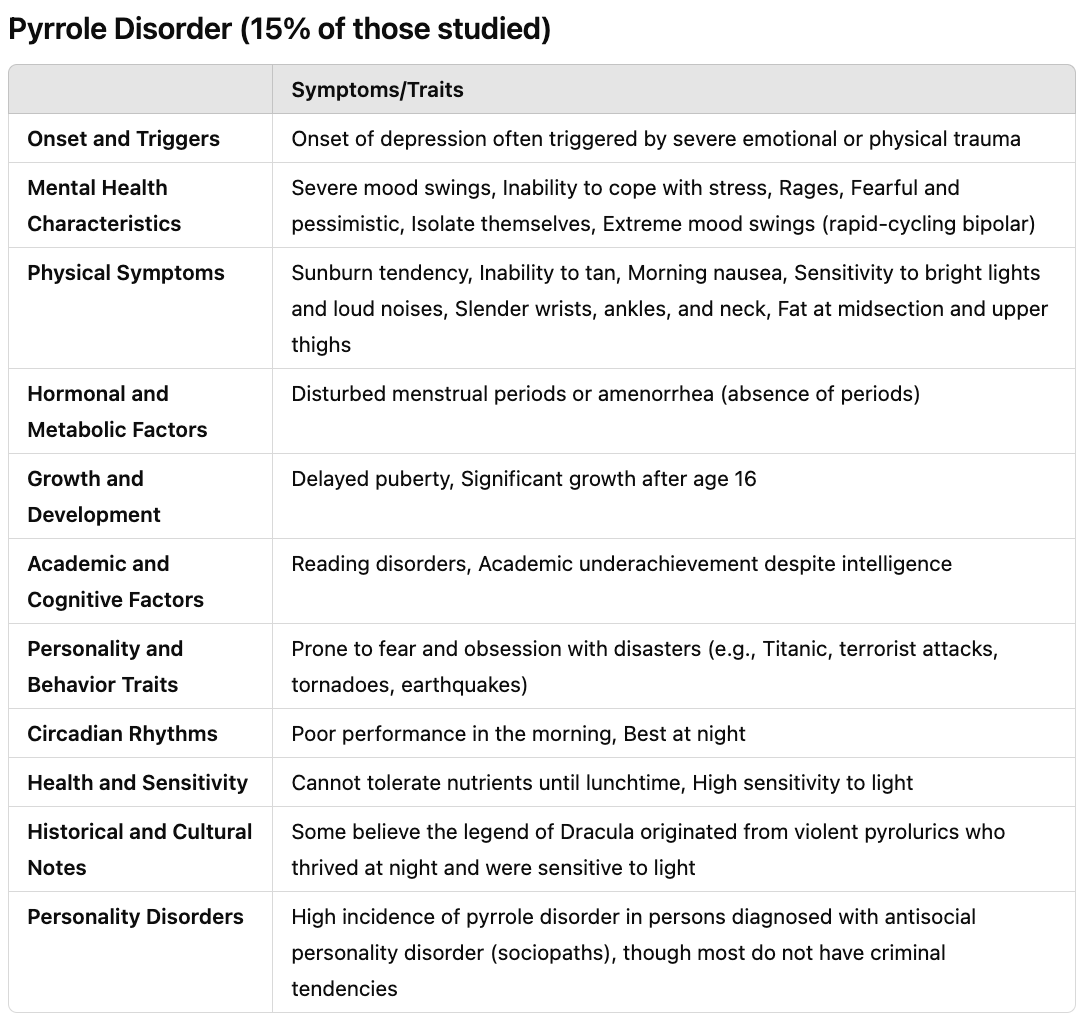

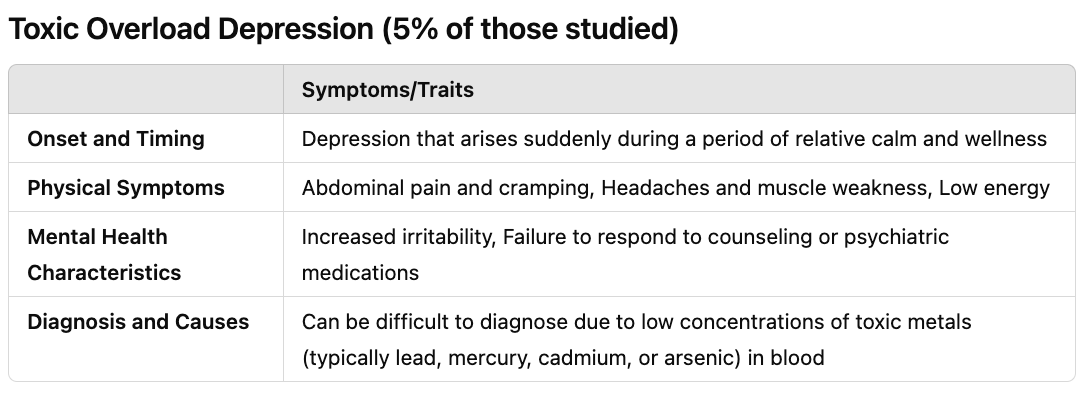

William Walsh analyzed the blood of 2,800 individuals with depression and discovered there were five common patterns of depression.

Note: these tables were derived from the information within Walsh’s excellent book Nutrient Power: Heal Your Biochemistry and Heal Your Brain. In Walsh’s experience, it is ideal to work with someone trained in nutritionally rebalancing metabolic depression as providing the wrong micronutrient can sometimes make things worse.

Some of the reasons this framework is beneficial are:

•If the metabolic biotype of depression is recognized, it can frequently be safely and permanently treated with natural therapies (e.g., copper overload is highly applicable to postpartum depression).

•It explains why patients will often have very positive or negative responses to medications (e.g., SSRIs are helpful for undermethylators but cause severe reactions for overmethylators). Likewise, it helps predict if patients will have an adverse reaction to supplements or other medications (e.g., undermethylators tend to have histamine sensitivities—something which often worsens with psychiatric medications).

•Anxiety often occurs concurrently with depression in these biotypes and hence can be treated (or fully resolved) by treating the biotype.

•These individuals have different responses to benzodiazepines. Specifically, undermethylators have a poor response to them, overmethylators have a positive response to them (as overmethylation depletes GABA), and those with a copper overload find benzodiazepines improve their anxiety but not depression (whereas SSRIs improve their depression but worsen their anxiety).

Lifestyle Causes of Anxiety

When there is too much stagnation in the body (particularly in the head), individuals have a tendency to overthink things. This I believe, explains why:

•A large meta-analysis found physical activity is 1.5 times more effective than psychiatric medications and psychotherapy at reducing mild-to-moderate symptoms of depression, psychological stress, and anxiety than medication or cognitive behavior therapy. This, in turn, ties to routine walking being one of the most important things we can do for health and longevity, but sadly, many adults do not.

•Conditions that create fluid stagnation in the body (ie. COVID-19, vaccine injuries, or cancer) often create depression and anxiety.

•We frequently observe that tight or synthetic clothing (discussed further here) makes individuals more prone to anxiety, something I believe results from both blood and lymphatic flow being directly constricted by the clothing. Tight clothing restricting one’s breathing (this is often extremely important to address when treating anxiety), and synthetic fibers create positive charges (which then adversely affect the physiologic zeta potential and create fluid stagnation).

•Many approaches that improve stagnation in the body improve anxiety (e.g., sexual intercourse, hot bathing, and electrical grounding have been found to decrease anxiety).

•Excessive time on the computer creates anxiety, particularly since blue light overstimulates the brain and pulls you into your head (e.g., I feel much calmer writing when I use a blue light blocking technology).

•Many traditions (e.g., Chinese medicine) believe that anxiety results from too much energy being in the head, and hence focus on making individuals be grounded (which often works).

One of my general beliefs is that there has been a massive decrease in the vitality of the human species (as for the last 150 years, again and again, I’ve found new illnesses emerged, the rates of chronic illnesses kept increasing, and natural therapies which previously were highly effective in treating illnesses became much less effective for the current conditions).

Collectively, I believe much of this results from modern technology, nutritional depletion, circadian disruptions, and fluid stagnation within our bodies, and that beyond this affecting physical health, it also affects emotional and mental health. Because of this, the treatments that are utilized to treat anxiety only have marginal efficacy, and one can often try very hard to stop overthinking things, but nonetheless still do so (as their anxiety has a physiologic cause).

Treating Anxiety and Benzodiazepine Dependence

In my experience, it is always preferable to deal with the underlying causes of anxiety as doing so safely creates permanent solutions to the issue, but in many cases this is not feasible (e.g., because the patient lives far away or you can only spend a limited amount of time with them). Because of this, I’ve looked at a variety of natural anxiety aids over the years, and found quite a few that clearly help but lack the immense risks of benzodiazepines. Likewise, there are a variety of other promising options that have not received that much attention from the medical field. Conversely however, I’ve also known otherwise highly talented colleagues who never were able to successfully treat anxiety naturally.

In the final part of this article, I will discuss each of those methods, the approaches we find effectively treat anxiety (e.g., supplements, other natural therapies, where other anxiety medications are appropriate, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, and beneficial mind-body therapies), and some of the most effective approaches we have identified for withdrawing from benzodiazepines.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Forgotten Side of Medicine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.