Ozempic and Fen-Phen

History has a remarkable way of repeating itself

Note: this article is posted twice here due to a Substack email server issue. The current article readers are commenting on can be accessed at this link.

Story at a Glance:

•In early 2023, a private conference attended by heads of the pharmaceutical industry and large investors hosted the head of the FDA as its keynote speaker. That conference promised that anti-obesity drugs and Alzheimer’s drugs would be the most profitable investment opportunities in the years to come. Since that time the FDA has taken numerous questionable actions to push these drugs on the populace.

•The most popular anti-obesity drug is Ozempic. In the last two years, we’ve seen a relentless push for it to be given to everyone (including children) which has involved a number of shockingly appalling marketing tactics. Remarkably, the stampede for Ozempic is almost identical to what happened with fen-phen, a wildly popular weight loss drug that was eventually pulled from the market due to it frequently causing severe heart and lung issues.

•Like fen-phen, the weight loss from Ozempic is temporary and disappears once the drug is stopped (requiring the patient to become a permanent customer). Worse still, Ozempic has a variety of common and severe side effects due to it paralyzing the digestive tract.

•In this article, we will review the common causes of obesity (including many which are rarely if ever discussed) and our preferred methods for safely and effectively losing weight.

In 2006, a satirical movie was made to illustrate the inevitable consequences of dumbing down society. Since then, it’s become a cult classic due to how many things it predicted (which seemed absurd then) that subsequently came true. One of the many themes in the movie was everyone mindlessly endorsing a Gatorade-like drink because its manufacturer had bought out the Federal government:

Sadly, this has also happened in America. More specifically, the majority of food consumed in America comes from a few crops (e.g., corn, wheat, soy, and canola). This is due to nonsensical farming subsidies (which essentially force farmers to mass produce crops and then sell them below cost), making these crops so cheap that for the processed food industry that they are then molded into all the processed foods we consume. This is incredibly problematic because:

•Most of those foods are not good for you to consume and hence create a variety of significant health issues, including diabetes and obesity.

•Since they are not good for you to consume, the body has a natural aversion to them (which makes them hard to sell).

•To overcome that aversion, those foods were mixed with a variety of highly addictive substances. More unfortunately, in the 1980s, Big Tobacco bought out the processed food industry and then, as they had done with cigarettes, prioritized making processed foods as addictive as possible (which is documented here).

•None of the predatory industries have anything to lose from people being hooked on unhealthy foods, which create chronic illnesses, as that simply means more lifelong customers for each industry (e.g., Big Pharma).

Because of this, for years, many activists (myself included) have tried to bring awareness to the importance of natural foods and the critical need to change America’s farming subsidies to something that encourages the availability of healthy foods—but many of these pleas have fallen on deaf ears. Fortunately, the new media climate created by widespread skepticism to the COVID-19 response and the ability for persuasive messages to rapidly disseminate through the independent media (e.g., Twitter) has caused many forgotten sides of medicine to come to the public’s attention, including the systematic failures in our food supply due to it having been bought out by the processed food industry.

In turn, it’s been remarkable and inspiring to watch how a brother and sister duo (which includes a Stanford doctor) has brought an immense degree of attention to this issue. Many of their interviews (e.g., this one and this one) each got millions of views, and they were invited to advise two of the three presidential frontrunners directly.

Two days ago, RFK Jr. announced his decision to support Trump’s election—a move which likely decided the 2024 election. In his speech, he cited his three primary reasons for running—stopping government censorship of free speech, stopping the war in Ukraine, and the catastrophic (but largely invisible) epidemic of chronic illness that is gripping the country. In that speech (which I would highly advise watching), RFK Jr. emphasized that much of our issues are due to the pharmaceutical and processed food industry having bought out our government agencies and that corruption has metastasized to the point that the foundation of our nation is being torn apart:

Note: I’ve done quite a bit to promote RFK Jr’s candidacy (e.g., I worked behind the scenes to help promote his campaign launch). I did this in part because his three reasons for running were also the three most important issues to me. Additionally, due to dynamics at play (e.g., the large number of COVID vaccine injuries), I suspected the presidential race would unfold in a manner where RFK Jr. would gain a platform that would be able to expose the American public to the corporate corruption of government creating an epidemic of chronic illnesses and that a pivotal window could emerge (i.e., now) where he could leverage his influence to address it.

RFK’s endorsement has already made a much larger impact than I could have imagined. For example, recently he was invited on Fox News to discuss the major issues in our food supply (e.g., the seed oils which are creating widespread metabolic dysfunction and dangers of artificial food coloring), both issues I’ve long believed were essential for the public to know about—but never expected to see receive mainstream news coverage.

Note: I believe that most of America’s food problems originate from Earl Butz (Nixon’s Secretary of Agriculture), who held the belief America’s farmers needed to switch to cultivating large (chemically intensive) farms instead of the more traditional small farm model which had previously characterized America’s agriculture. Butz’s mantra, "get big or get out" became a dogma within the US Department of Agriculture and is a major reason why locally grown (healthy) food is so unaffordable and inaccessible for much of the country.

Pharmaceutical Sales

One thing I’ve been immensely curious about is what life is actually like behind the scenes within the pharmaceutical industry. In turn, I’ve shared anonymous accounts of insiders, alongside public testimonials from whistleblowers (e.g., see this article and this article about the sociopathic sales-focused culture within Pfizer).

To some extent, I’ll admit, my impressions are a bit biased by a presentation GlaxoSmithKline gave their sales reps:

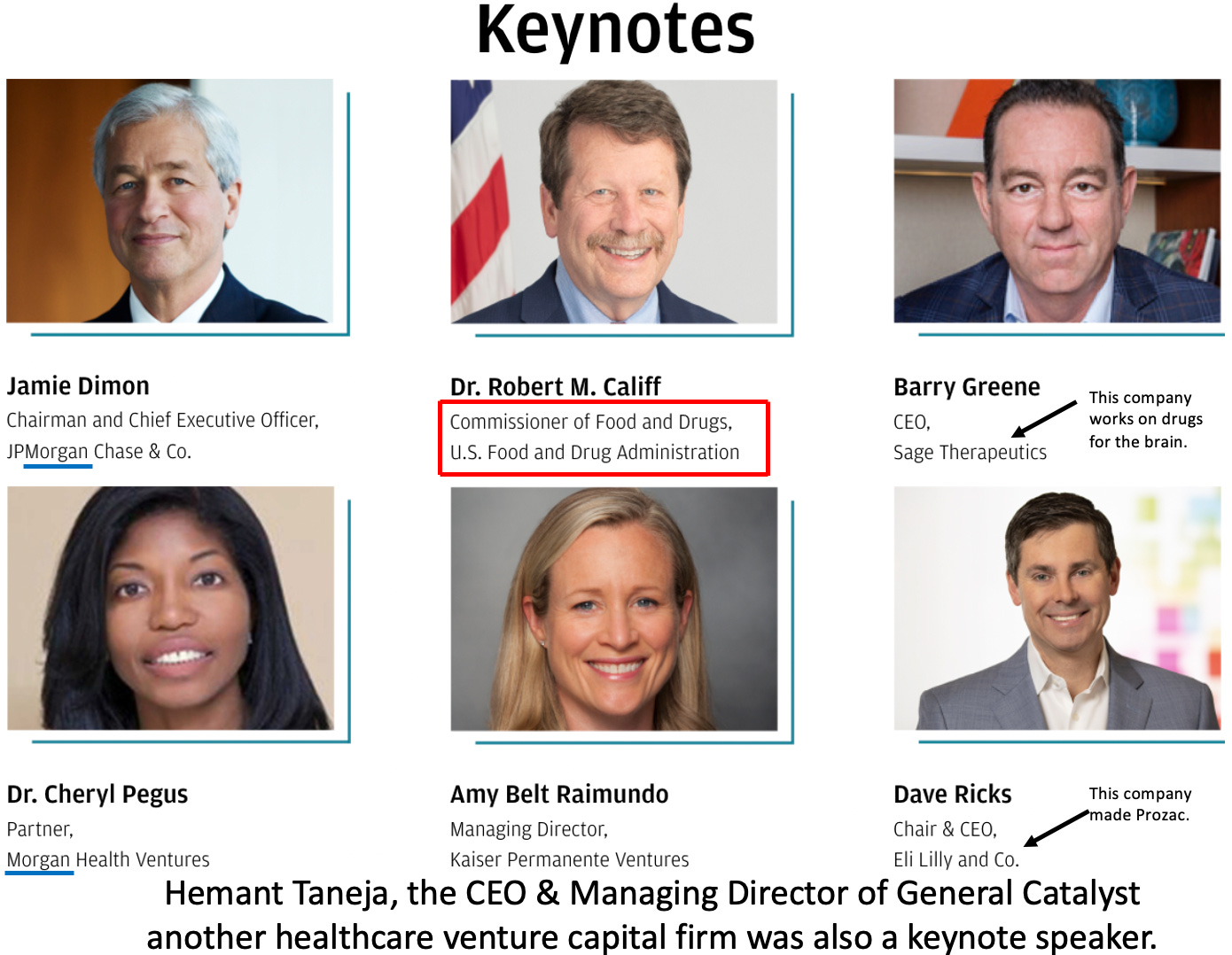

Last year, Kim Witczak a pharmaceutical safety advocate, tipped me off about JP Morgan’s annual healthcare conference, a private invitation-only event described by JP Morgan as “the industry’s biggest gathering.” The 41st conference, from January 9-12, 2023, was the first event hosted in person since the pandemic started (it was hosted in San Francisco). Given this event's impact on the year to come (as it’s specifically catered to large investors and hence sets the pharmaceutical industry’s priorities), Kim made a point to glean as much as she could from its website.

Given what she found on public display, I can only imagine what was said behind closed doors (e.g., consider the previous GSK video).

First, consider how enthusiastically they endorsed the profitability of two new types of drugs:

Note: the sound on the second one is a bit off (it sounded more “inspirational” in the actual video), but it can no longer be viewed as Chase deleted it following the publication of the original article on the conference.

In that video, the most important part was Chase’s projections for this new industry:

Note: the GLP-1 drugs include Trulicity, Wegovy, Mounjaro, Byetta, and Ozempic. While there are some distinctions between the drugs, I will henceforth primarily refer to all of them as “Ozempic.”

Second, consider who the keynote speakers at Chase’s conference were:

Note: Califf has long been an incredibly controversial FDA commissioner due to his immense conflicts of interest (e.g., in 2009 he was passed over for the position due to his connections to the pharmaceutical industry, but at the end of Obama’s term and throughout Biden’s tenure, the system became more corrupt he was twice able to secure a nomination).

To repeat—the head of the FDA was a keynote speaker to investors about the incredibly lucrative opportunity they could expect from these new drugs—implying that the FDA would do everything it could to push them through. As it so happened, to quote Witczak:

Interesting to also note, Califf was keynote speaker on opening day and out of the blue, the FDA granted accelerated approval to the second controversial Biogen Alzheimer drug on Friday [three days before the conference] without an Advisory Committee. How great to be able to announce to the healthcare biotech industry that one of their new drugs was just granted accelerated approval.

Note: an even more controversial approval had proceeded it (where the FDA overrode its own panel to approve an expensive, dangerous, and ineffective Alzheimer’s drug which resulted in three of the experts on the panel resigning with one stating it was “probably the worst drug approval decision in recent US history”). Shortly afterwards, the FDA gave a glowing press release on their approval of the drug—but due to how unsafe and ineffective the drug was, even with the FDA’s endorsement, rather than become the next blockbuster drug, it abjectly failed in the market and is now being discontinued by the manufacturer. For those interested, I discussed the immense scandal with existing Alzheimer’s drugs and the suppression of proven (but un-patentable) treatments for the disease here.

The Rise of Ozempic (semaglutide)

Once I saw this conference, given that it sets the course for the entire industry, I became fairly convinced that Ozempic would be aggressively marketed by the pharmaceutical sector in the coming year and that the FDA would do everything possible to expand the market. This happened so quickly that many began speaking out about it. Here for instance, I excerpted the key sections of Casey and Calley Means describing the staggering corruption that has facilitated Ozempic’s rapid rise throughout America:

In turn, we’ve had our “trusted authorities” wholeheartedly endorse giving this drug for weight loss and a constant slew of marketing to sell it for that (without any complaints from the FTC or the FDA). Given how desperate people are to lose weight, a rush has been created for the drug, and I am now seeing numerous sleazy clinics hang large banners outside stating that they offer Ozempic—something reminiscent of what I saw as the “safe and effective” opioid painkillers spread across America.

In fact, this campaign has been so effective that since 2022, there has been a shortage of these drugs (despite Ozempic’s manufacturer doing everything it can to ramp up production) to the point that many have been seeking out alternative sources of Ozempic (which Ozempic’s manufacturer and “the experts” are of course trying to clamp down on).

In observing this campaign, alongside an aggressive push to no longer treat obesity as a lifestyle disease (as it can then be prevented with something besides a pharmaceutical), three things in particular have jumped out at me as the insatiable industry has moved to expand this market to every conceivable demographic.

1. African Americans—As Calley Means revealed, Ozempic’s manufacturer paid off the NAACP (one of the premier groups advancing the rights of African Americans in the United States) to become a lobbyist for Ozempic and attack any attempts to withhold giving Ozempic to African American community as a vile act that perpetuates systematic racism.

2. Children—shortly before the Chase conference (on December 22, 2022) the FDA approved semaglutide to treat obesity in children 12 and older, while on January 9, 2023 (the first day of the Chase conference), the American Academy of Pediatrics published a set of authoritative set of guidelines for treating childhood obesity which strongly endorsed giving them the GLP-1’s. Specifically it stated:

This recommendation was followed by a tepid endorsement of most of the available weight loss drugs and a strong endorsement of the GLP-1s—in effect having those guidelines serve as a strong promotion for giving Ozempic (or related drugs) to children on the basis of a 68 week study. Given that drastically altering digestion during childhood will likely affect the long-term development of the body, it seems quite questionable to assume a (likely doctored) 68 week study can accurately predict putting children on these drugs will prevent them from developing long-term complications.

Note: the best parallel I can think of to this are the proton pump acid reflux medications, which work by completely suppressing the stomach’s production of acid. As stomach acid is essential for digestion, many leaders in the natural health field predicted the long-term use of these drugs would lead to a variety of significant complications (e.g., depression, osteoporosis, stomach cancer, allergies, and autoimmune disorders). Still, these concerns were largely ignored since the standard medical training omits mentioning the importance of stomach acid. In turn, it took decades for the research to emerge that these drugs do in fact have those side effects (which conveniently happened once they were off-patent). That subject, as well as the natural ways to treat acid reflux (e.g., by increasing rather than lowering stomach acid levels) are discussed further here.

3. The Elderly—One of the major barriers to selling Ozempic is that it is so expensive (1,000-1,500 per month), most patients cannot afford it without insurance. One of the primary barriers to insurance coverage is that the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 specifically prohibited Medicare from paying for drugs prescribed for “weight loss.” In turn, the industry has been aggressively lobbying to have this law overturned, and an “obesity rights” coalition (which is primarily funded by Ozempic’s manufacturer and previously lobbied the American Medical Association to make obesity be declared a disease requiring pharmaceutical treatment) has now successfully gotten a law doing just that through committee (which if passed is expected to cost Medicare between 3.1 to 6 billion dollars annually).

If you take a step back, this raises an interesting question. Why on earth is there a law banning Medicare from paying for obesity treatments?

Note: paying off third party patient advocacy groups to promote the pharmaceutical industry’s interests is a very common practice. For example, I recently discussed the National Multiple Sclerosis society, an organization which has existed for 78 years, now takes in 200 million annual but has failed to produce any meaningful benefit to MS patients. Conversely, many over the years have shown that this organization has ruthlessly suppressed proven cures from MS which cannot be patented by the pharmaceutical industry.

The Rise and Fall of Phen-Fen

A key theme I’ve tried to illustrate in this publication is how often the exact same catastrophe repeats in medicine because each previous incidence of it gets erased. What I find remarkable about Ozempic is how similar it is to the fen-phen saga, except that at that time, the FDA was still willing to upset the industry and (sometimes) remove dangerous drugs from the market.

Phentermine (introduced to the USA 1959) and fenfluramine (introduced to the USA in 1973) were two marginally effective weight loss drugs that never caught on. In 1979, a professor of clinical pharmacology who had recently become a director of an FDA division for approving new drugs believed obesity needed to be treated as a medical (rather than lifestyle) disease and decided to see if they’d work better once combined. He then conducted a four year study of 121 (mostly women) obese patients. He cycled them between that drug combination or a placebo, finding that his combination caused them to be less hungry and lose weight while the placebo did the opposite. Not noticing any side effects besides weight gain and hunger once the drugs were stopped, he then spent almost a decade trying to get his study published, and eventually in 1992, a journal did.

Word of his magic cocktail spread like wildfire, demand surged for fen-phen and before long doctors around the country were converting their practices into pill mills (e.g., this New York Times article about that era cites an infectious disease doctor who paid a chiropractor to hand out blank prescriptions he’d written to patients).

Some, like Dr. Dennis Tison, a Sacramento psychiatrist, devoted his entire practice to fen-phen, buying the drugs wholesale and dispensing them in his office to thousands of patients. Like many doctors, he advertised on the Internet that he prescribed fen-phen. ''I got calls from all over the country,'' Dr. Tison said. ''People would say, 'I want the meds and I will pay anything.' ''

Dr. Tison said he saw nothing wrong in his practice. He criticized storefront clinics springing up overnight in California strip malls, ''like cockroaches,'' he said, handing out the drugs to anyone who walked in. ''A lot of doctors viewed this as a cash register,'' he said.

Note: I also heard of cases of people (e.g., pharmacists) who were desperate to lose weight and lost their licenses after they got caught stealing fen-phen for themselves.

This lucrative market caught the industry’s attention. In 1995, another pharmaceutical company petitioned for the approval of a similar drug. Through their supporters within the FDA’s approval committee, they were able to get it approved despite great apprehension from the panel. In April 1996, the FDA approved what would likely be a lifelong drug despite the studies for it only lasting a year.

A few months later, reports began emerging that fenfluramine caused heart valve damage. After extensive investigation, it was eventually discovered that fen-phen:

•Had already caused one-third of users to develop asymptomatic heart valve damage—which was quite significant given that the drug had only been on the market for a few years and similar damage typically only affected around 1% of the population.

•Had caused many cases of severe heart valve disease (in their initial search the FDA identified over 100 cases).

•Increased the risk of pulmonary hypertension (a fairly severe disease) by up to 30 times, with the risk increasing the longer someone was on this drug.

Given the magnitude of the situation they were facing, the FDA banned fen-phen (or more specifically fenfluramine (as it was suspected to be the main culprit), and a few years later Medicare was outlawed from covering weight loss drugs. Disappointed they’d lost their market, physicians experimented with other phentermine combinations (e.g., they paired it with Prozac, another fluorinated serotonin increasing agent and called it phen-pro). Numerous lawsuits followed, and the manufacturers of fen-phen were forced to spend over 13 billion in settlements.

What is particularly remarkable is what the FDA official who conducted the pivotal trial that showed fen-phen was safe and effective stated after its severe complications were discovered. To quote the NYT:

''I figured, gee whiz, these drugs have been on the market for 10, 12 years,'' he [the FDA official] said. ''Everything must be known about them.''

And certainly it never occurred to him to look for heart valve problems because no drug, with the possible exception of high doses of ergotamines for migraines, had ever been known to damage heart valves.

Note: another interesting parallel with Ozempic from the days of fen-phen is that physicians are experimenting with a variety of different uses of the drug that they believe will lead to weight loss but do not have evidence supporting them.

The Risks and Benefits of Ozempic

Prior to Ozempic and its ilk being marketed as anti-obesity drugs, I was mostly familiar with their uses for diabetes, as many of my colleagues believed they were quite helpful for the disease. Given that some of these colleagues were fairly conservative with which drugs they would use and excellent clinicians, I took their opinions into serious consideration. However, I also noticed that I was repeatedly seeing patients develop unusual gastrointestinal complications from the drugs (including one hospitalization of a distant relative), so I held to the perspective the drugs were too new for it to be appropriate to prescribe them despite the fact they could potentially be immensely helpful for patients with diabetes.

After they started being used as weight loss agents (where their dose is much higher—0.5-1.0mg vs. 1.7-2.4mg—frequently being almost five times greater), we started noticing that we’d see more and more patients who should have never been prescribed the drug and are taking enough of it (often even overdosing) to drive themselves into cachexia. These patients are easy to identify as they don’t look normal and have a somewhat sick and somewhat anorexic appearance.

In terms of the abuse of weight-loss drugs, “nothing compares to the phenomenon that we’re seeing right now with these GLP-1s,” said Melissa Spann, a psychotherapist and the chief clinical officer at Monte Nido, an eating disorder treatment group that runs 50 programs and in 28 states virtually.

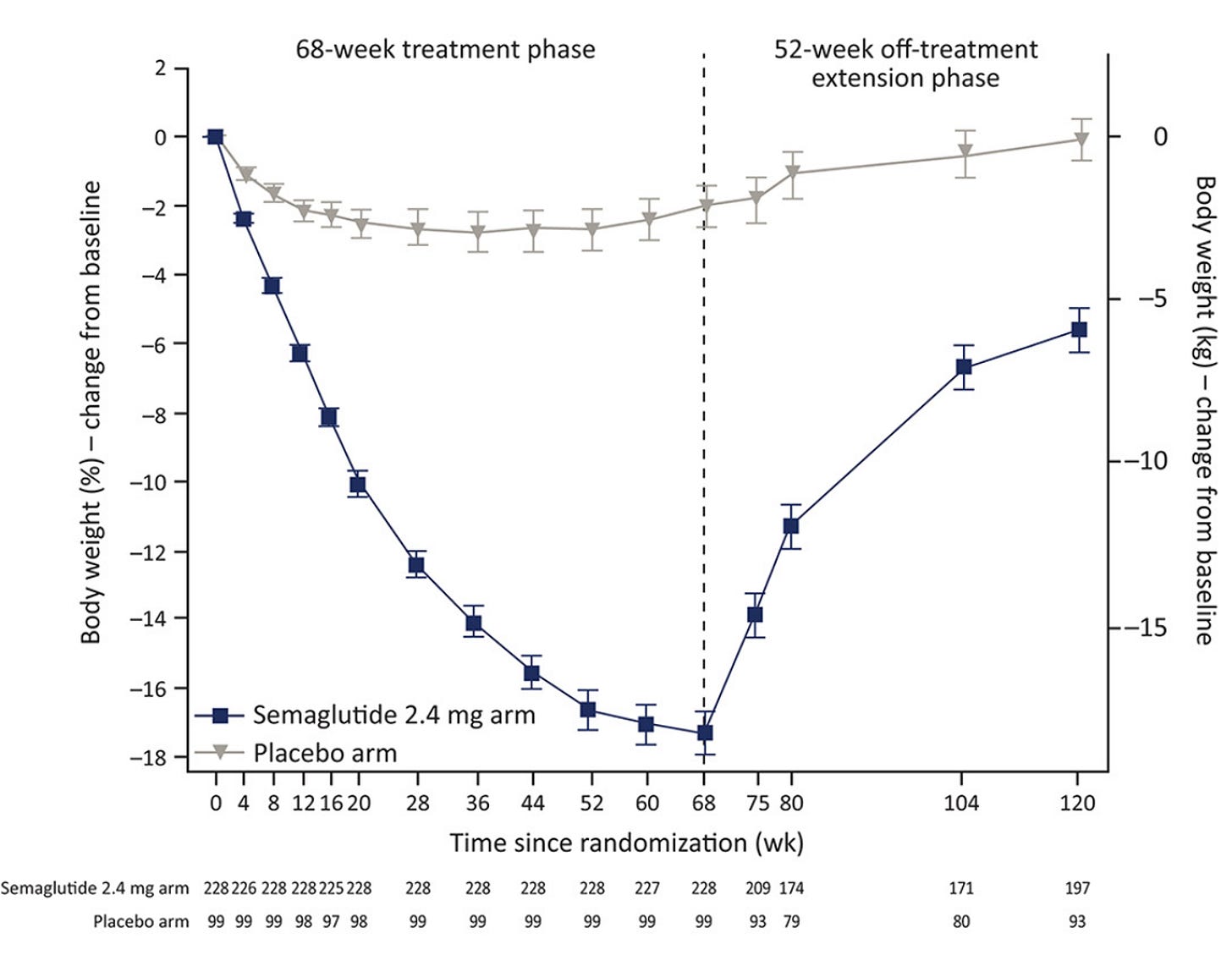

I then looked into the data on the GLP-1 drugs and noticed a curious pattern—like fen-phen, the weight lost was rapidly regained once the drug was stopped. To illustrate, here are a few graphs from the pivotal trials of these drugs.

First, a pivotal trial of using the full (2.4mg) dose of Wegovy (which like Ozempic is another name for semaglutide) each week, inadvertently shows that most of the participants could not stay on the drugs for a prolonged period:

Second, the (small) pivotal trial for giving this to children showed they began regaining their lost weight once they stopped the drug (and conveniently only tracked this for a short period as a much greater weight likely would have occurred over time).

Third, when the effects of withdrawing the drug were tested, the lost weight was clearly shown to return (alongside a gradual decline of the number of people who could stay on the drug):

Furthermore, this effect was also seen in a related drug:

In short, I would argue that having to spend 1000 dollars a month for a bit of weight loss, which then disappears once you stop the drug may not be the best deal. Conversely, I suspect a key reason why this side effect has been publicized is because the goal of the pharmaceutical industry is always to have a large number of people perpetually using a high profit margin product (e.g., a monthly course of the thousand dollar Ozempic costs less than 5 dollars to make), so any product which creates intolerable withdrawals when one stops (e.g., the SSRI antidepressants or the PPI acid reflux medications) constitute an ideal product.

Note: while I believe Ozempic is not a good agent for weight loss, I will mention that a few of my colleagues have had success using low doses of Ozempic for a short term period to eliminate specific food cravings they believe are detrimental to their patients as Ozempic removes the desire of the food long enough for the patient to be able to permanently break the addiction (provided they then make an active effort to avoid the specific food).

Unfortunately, in addition to being a scam, Ozempic has a few major issues.

First, as mentioned before, since its primary mechanism of action is reducing the desire to eat, the body can become excessively malnourished. Ozempic malnourishes the body in a very characteristic way (hence why we’ve started being able to spot these patients). Likewise, since this effect is quite noticeable in the face, it has come to be known as the “Ozempic Face.”

Note: since the breasts are largely fat, a similar effect can happen there, with many women developing deflated and sagging breasts after using Ozempic.

Second, the GLP-1 drugs were designed to resist breaking down within the body, so they would only need to be injected once a week (resulting in their average half life being approximately seven days whereas the natural GLP-1 protein has a half life between 1.5-5 minutes). Since the GLP-1 is responsible for slowing digestion in the body, drugs like Ozempic significantly slow digestion and can create a variety of gastrointestinal issues from doing so (e.g., a study of 25,617 real-world patients found these drugs cause a 3.5 times increase in the rate of intestinal obstruction).

The most comprehensive study I’ve found of the severe side effects of GLP-1 drugs (e.g., Ozempic) sourced from 16 million patient’s medical records found that the drugs were strongly linked to a variety of side effects that frequently required hospitalization. Specifically, when compared to another weight loss combination not typically associated with these effects, GLP-1 users were found to have:

9.09 times greater risk of pancreatitis

4.22 times greater risk of bowel obstruction

3.67 times greater risk of gastroparesis (which means you can barely eat because the stomach is constantly full—and in many cases after Ozempic, ends up being permanent)

1.48 times greater risk of biliary disease (e.g., painful gallstones)

Note: the exact risk depended on the type of GLP-1 drug used (e.g., Ozempic appeared to cause roughly 1% of users to develop gastroparesis within a year).

Another theme I’ve emphasized here is that severe adverse events are typically much rarer than moderate or minor ones. Given how frequent these severe effects are, it should come as no surprise that less severe ones are even more common.

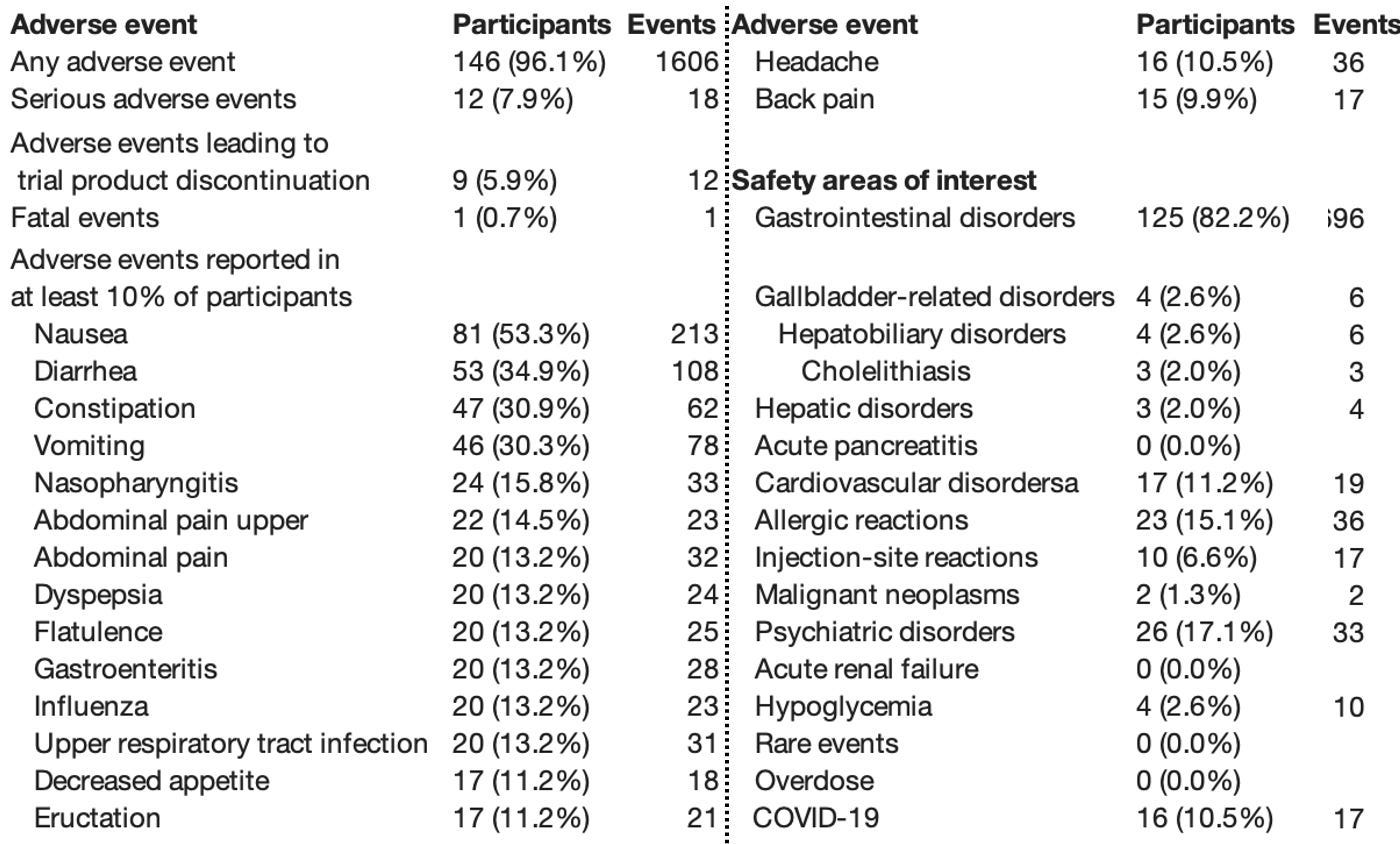

For example, consider this study of 175 people on the weight loss dose of Ozempic:

Likewise, consider how many adverse events were acknowledged within a trial sponsored by Ozempic’s manufacturer:

Sadly, these aren’t the only side effects. For example, in addition to lawsuits being filed against Ozempic for gastrointestinal disorders such as gastroparesis, lawsuits are also emerging for other severe conditions such as vision loss. Likewise, evidence is now emerging linking Ozempic to an increased risk of suicidal ideation (e.g., a 45% increase has been observed). Animal experiments are showing it distorts the architecture of the small intestine (which can lead to poor nutrient absorption or chronic intestinal obstructions), and many of the GLP-1 drug labels state the drugs may be linked to thyroid cancer.

Note: in a previous series, I discussed one of the largest issues with the SSRI antidepressants—because they are given at a very high dose, individuals frequently experience severe withdrawals when their dose is changed. These withdrawals, in turn can trigger suicidal behavior, psychosis, or violent behavior, which is sometimes homicidal (and a common theme in most school shootings). A major issue with Ozempic is that since it slows the rate at which the stomach empties, it alters and delays the absorption of psychiatric medications. Since the users are often very sensitive to changes in their dose, many reports now exist online of significant psychiatric destabilization occurring in Ozempic users who were also on psychiatric medications. This may in part explain why the above study found that the 45% increased risk of suicidal ideation from taking Ozempic became a 345% increase in those who were already taking SSRI antidepressants.

One of the things some find fascinating about medicine and others find immensely frustrating is that an almost identical set of symptoms can be caused by very different factors depending on the patient (e.g., while there are common causes of chronic fatigue, there is no single cause which applies to most people).

Since medicine has been transformed into a discipline that revolves around giving the same standardized protocol to everyone, this reality necessitates those protocols utilizing therapies which target the symptoms of a disease rather than its underlying cause—an approach that typically gives a temporary alleviation of the presenting symptoms while the underlying disease simultaneously worsens (which in turn requires more and more symptomatic drugs to “address” it).

Note: while similar diseases typically have a wide variety of different causes, in certain cases, a unifying cause (e.g., poor microcirculation due to a chronically impaired zeta potential) does exist that can explain a myriad of diseases. However, this is never publicly discussed since it threatens too many disease markets.

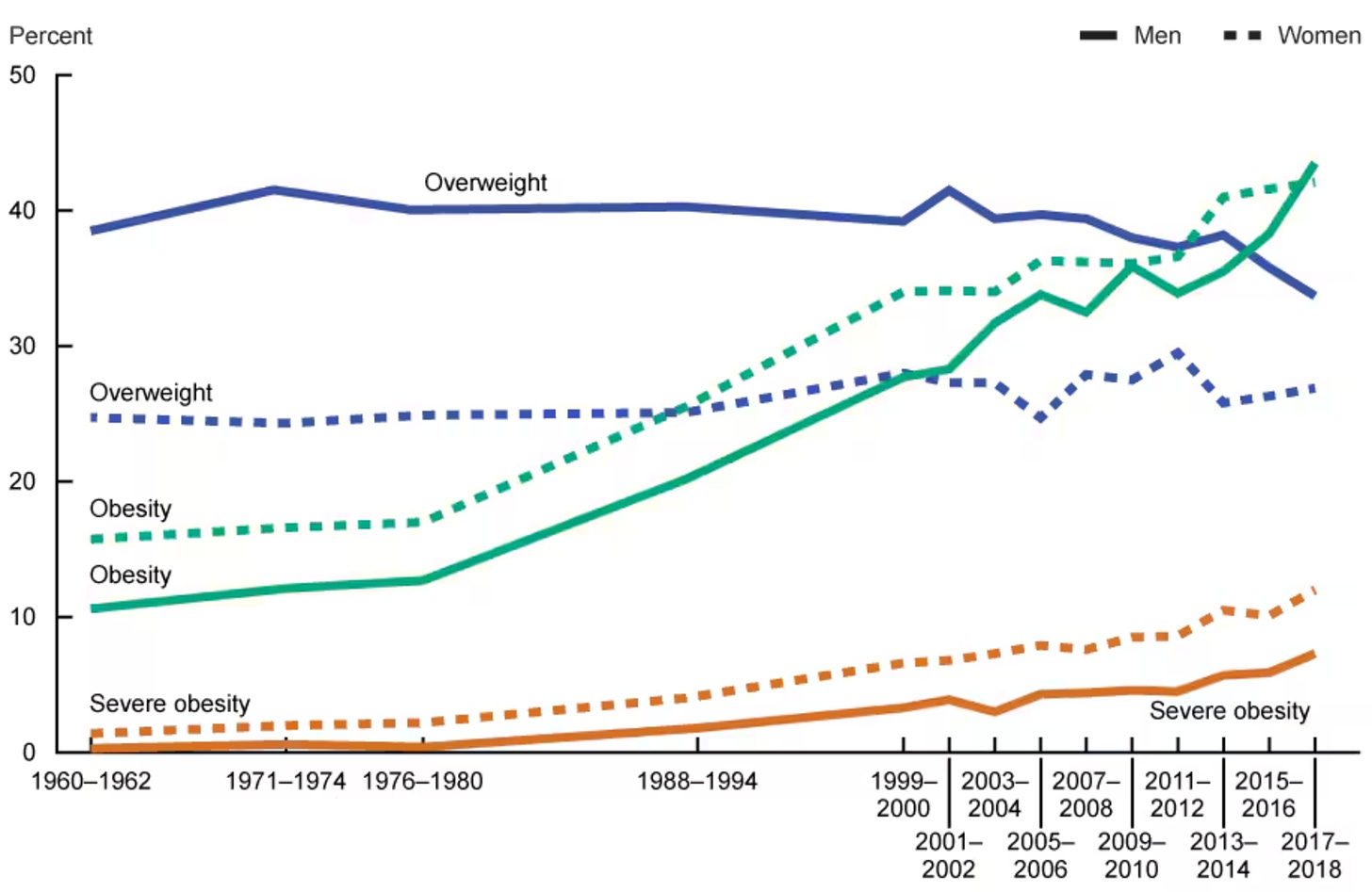

In America’s case, it’s very clear that obesity has been continuously rising, and that like many other chronic illnesses, we have no explanation for why this is.

The most common explanations were are given include:

•We are eating too much food now and having a sedentary lifestyle.

•The core ingredients of our diet (the monoculture grains like corn) are highly effective at making individuals gain weight and hence should not compose the majority of our diets. For example, excess sugar is transformed into fat and cholesterol. Yet, despite this being well known, due to decades of fraudulent research done to protect the food industry, animal fats are normally blamed for the consequences of eating grain heavy diets.

•Gut microbiome dysbiosis triggers obesity (e.g., see this review).

•There is widespread metabolic dysfunction in society (e.g., due to mitochondrial or thyroid dysfunction), which causes the same amount of calories to make us gain significantly more weight than they otherwise would.

•Specific additives in our foods (e.g., seed oils or high fructose corn syrup) rapidly trigger obesity within the body.

•The estrogen mimicking compounds present throughout our environment (e.g., from plastics, soy, or birth control pills designed to resist degradation and persist in the water supply) are causing widespread obesity.

•A less overt version of type 1 diabetes (where the immune system attacks the pancreas and disables its production of insulin) occurs which leads to a chronic insulin deficiency. This is in part due to the fact we’ve seen numerous cases where a sensitizing trigger caused an individual to develop diabetes. One of the best examples was a colleague’s relative who went on a deer hunting trip, and then every member of his group (who all ate the same deer) subsequently developed diabetes. We felt the only thing that could have accounted for this cohort example was a vaccine their entire unit got in the military or something that was in the deer (e.g., a parasite or possibly CWD).

Note: there are also other more mainstream explanations given I do not agree with (e.g., that cholesterol heavy foods like animal fats make us gain weight).

The essential challenge with these explanations is that all of them seem to apply in certain cases but not others, and in parallel, weight loss approaches which help for one individual do not help for another. However, rather than acknowledge this, we’re simply being told the true answer is a lifetime of Ozempic.

In the final part of this article, I will discuss the key factors we have found often underlie obesity or food cravings (many of which are almost never discussed) and the most effective ways we have found to lose weight or reverse metabolic dysfunction (e.g., diabetes)—most of which sadly are forgotten sides of medicine—especially because the actual causes of obesity are rarely discussed (rather the focus is simply on lecturing patients or pressuring them to become lifelong pharmaceutical customers).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Forgotten Side of Medicine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.