The Art of Memorization

How natural medicine can enhance your capacity to study, retain information and explore the depths of your dreams

Story at a Glance:

•Academic success is primarily based on one’s ability to memorize material. Unfortunately, the educational system rarely teaches students how to do that.

•Effective learning requires actively rather than passively engaging with the required material and being conscious of what is going on inside your body and mind so that you can determine which approaches are correct for you.

•Many of the same factors that determine overall health and neurological health (e.g., a healthy sleep cycle and adequate circulation throughout the body) also directly influence your capacity to study and memorize.

•In this article, I will review the various approaches and supplements that we have found to be the most helpful in improving memory retention and supporting academic success (along with increasing the lucidity of dreams if taken right before bed).

The primary mechanism our society uses to determine one’s eventual wealth and place in the social hierarchy is their academic performance. As such, many put forward an incredible sustained effort to succeed at each rung of the academic ladder, and in many cases, at the urging of their parents, begin that effort from a very young age. However, while a variety of justifications exist for the society adopting this convention, there are also major issues with it, such as:

•Far too many who go through it and put in a sustained effort to “succeed” end up with nothing to show for it.

•Because education has essentially established a monopoly on moving up the social ladder (which forces everyday citizens to participate in its rat race), it has no incentive to provide quality education to those it trains—particularly since unconditional federal support (e.g., student loans) subsidizes education and is allotted based on how many students attend each institution, not the quality of the education offered.

•Education primarily focuses on telling you what to do, not how to do it. As a result, those with inherent talent do much better than their peers, whereas many of those who simply try to do what they are told to do fall short regardless of how much effort they put in.

•By making people believe they need to be “taught to learn” through copying what the teacher does rather than encouraging the natural learning capacity of each student to emerge, the educational process makes students lose their inherent ability to learn or think critically.

Note: a recent study found that throughout history, whenever there are periods of internal conflict, states have introduced education reform that is designed to indoctrinate citizens to accept the status quo.

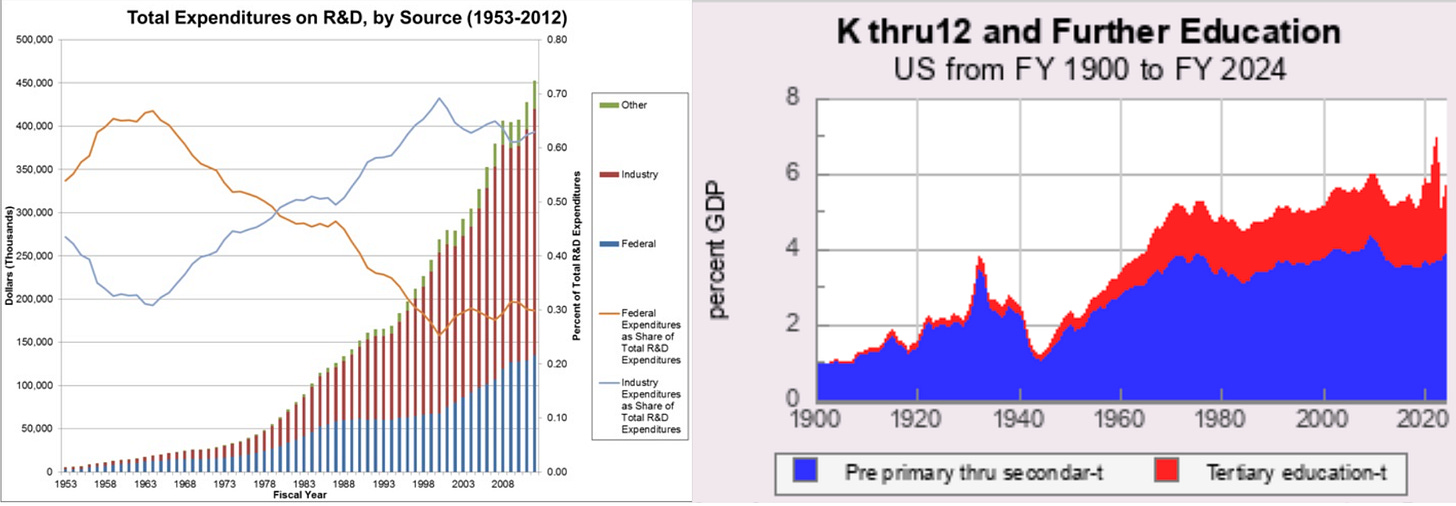

As such, the primary function of schooling has become more and more dependent on conditions of subservience and conformity rather than creating a generation of creative critical thinkers who can solve the issues our country faces and innovate solutions that advance us into the future. This in turn, is both highly unfair to those who are put through the academic grinder (but not inherently suited for success within it) and an immense waste of national resources. For example, as the years go by, we keep spending more money on research and education:

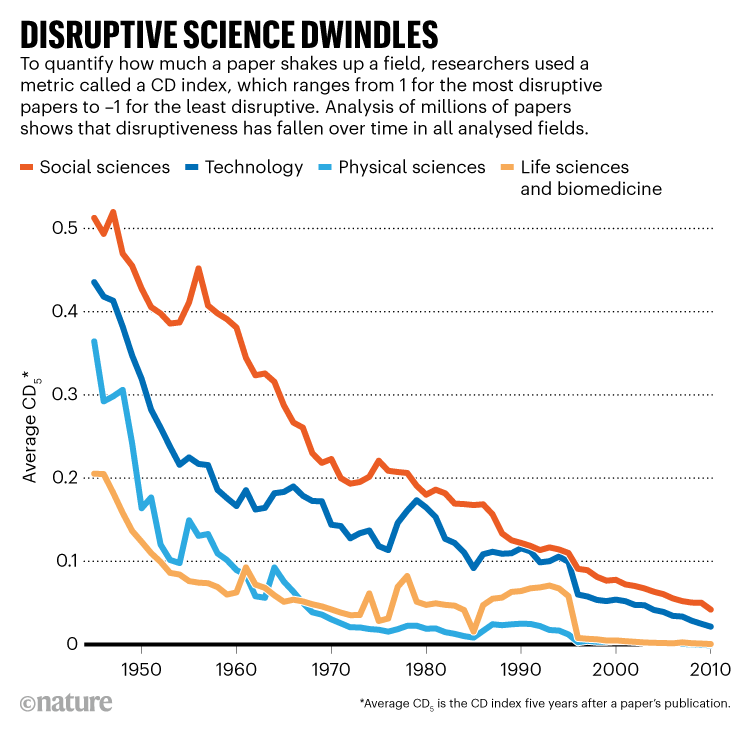

Yet primary educational outcomes (e.g., literacy) keep worsening, and valuable scientific innovations keep becoming rarer:

Note: I believe one of the most significant issues with the profit-focused debasement of American education is that it’s lowered the quality of the graduates who can fill our society’s institutions, thus lowering the quality of those institutions.

Studying

The primary metric determining success in education is how effectively one can memorize testable material. As such, a lot of education is compelling students to “spend more time studying” and dole out a myriad of punishments for those students who did not study enough. This in turn, touches upon one of my favorite phrases:

Work smart, not harder.

In my case, I believe much of my academic success boiled down to three things:

•In junior high, while learning a foreign language, I accidentally figured out how to use the sleep cycle to quickly memorize a lot of information.

•Because I recognized the value of natural health at a very young age, I avoided most of the things within our society which impair the sleep cycle or cognitive function.

•Because of the previous two things, there was less pressure on me to always be studying. As a result, I had a lot more time available to think about what I was studying and look into related sources of information.

This final point is particularly important as it cuts to the heart of the problem.

Students are constantly put under an immense amount of pressure to learn a lot of material, and to address this immense task, everything else gets cut out, so more time can go into memorizing the material that is taught. However, by doing this, their learning becomes much less efficient, so even though more time is spent studying, much less is learned.

Understanding vs. Memorizing

In most cases, the best way to memorize a topic is to both understand it and to know the justification for why it was taught to you in the first place. However, in most cases neither (especially the latter) happens. For example, when interviewing medical students, colleagues and I have found it fairly rare for the interviewee to answer why they were taught a specific piece of information (even within the area of focus they highlighted in their personal statement).

Typically, people recall information by having it connect to something else they know. As such, when you study a subject, but also take the time to explore it and make sense of each thing that is connected to it, those mental connections form, and the knowledge transforms from something you can hopefully recall to something that you just know (or can quickly recall by thinking about a connected subject you have a deep grasp of).

Likewise, understanding the value of learning something both fosters those critical connections but simultaneously allows the information to become something much more real you can directly take ownership of rather than an abstract fact you struggle to pull back to you (which again makes it far easier to recall).

When a light is turned on with a switch, most people don’t want to understand everything that allows that to happen; they just want to know that turning a switch turns the light on.

This lack of conceptual understanding is particularly common in medical education, where students are bombarded with a firehose of information they are expected to somehow memorize. As a result, there’s very little time for anything else (e.g., understanding the basis for it). Worse still, the hierarchal nature of medical education actively disincentivizes doing anything besides trusting the information being taught (as questioning any medical dogma can lead to harsh sanctions for the student).

I’ve long suspected this is by design as it both prevents students from ever exploring contradictory information and simultaneously creates an immense psychological investment in the value of their education, which makes them quite reluctant to question if parts of it are wrong. In my eyes, both of these are essential for the indoctrination physicians undergo, as many of the things they are taught don’t actually make sense if you really think about them—hence motivating and ensuring there is never enough time to question the medical curriculum.

Likewise, even if a student is skeptical about what’s being taught, being conscious of it often requires them to simultaneously hold two separate world views within their mind, as graduating from medical training requires each doctor to effectively present the orthodox version of medicine. Since that’s already an immense task, it’s often simply not possible to also hold any other worldview in one’s mind.

Note: I know people who had extensive backgrounds in natural medicine (and a great deal of clinical success with it) who then went to medical school and completely abandoned those disciplines because it was not possible for them to also have enough space in their minds to hold both perspectives simultaneously.

Active and Passive Memorization

When I was in medical school, to make studying more “fun” I did the following:

1. I would often procrastinate studying the tested material by instead learning about an interesting related topic (e.g., a correlate within natural medicine).

2. I would often look for holes or fallacies in what was being taught to us.

3. For each exam, I would try to study in a different way from how I had previously and see how the results compared to each previous attempt.

The value of the first two approaches should make sense (e.g. because they fostered more connections to the memorized material and preserved my love of learning—rather than viewing the course work I faced as something to be afraid of). However, of these, I learned the most from the third approach.

Originally, my desire to try to study differently each time arose because I knew that each subsequent examination would be more challenging than the previous (as the coursework in medical school ramps up). However, before long, I realized it was quite interesting to observe how I learned and continually experiment with it (making the studying process more fun to go through), and as time went on, I gained many insights about the process for both myself and others. These included:

•Many aspects of your environment (e.g., the lighting or how coherent or incoherent the music you listen to is) can significantly impact your ability to process and retain information.

•Different people learn differently, so there is no one size fits all approach. For example, some people are visually oriented, some are primarily auditory, and some are kinesthetic. Each group typically learns best through that specific channel (e.g., listening to numerous lectures versus looking at the material and then drawing it out, etc.).

•Similarly, many different study aids exist that work only for some people but not others (e.g., many of my classmates prioritized using flashcards, but I never found them helpful for me). Unfortunately, people tend to assert what works for them is also the best for everyone else, and one of the most common mistakes I see students make is being compelled by their peers to utilize a studying approach which is not actually the best for them.

Note: one of the unfortunate changes I’ve witnessed in medical students over the last decades is an increasing reliance on external study tools (e.g., online videos or demanding precise study guides and practice questions from their teachers) rather than students creating their own study materials from the presented material. Since active learning is critical for long term retention, I believe this passivity with learning is highly counterproductive.

•While studying, if you make an effort to stay consciously aware of what is occurring inside you, you are much more likely to develop your effective learning method. Essentially, when you learn a concept, you can either be disconnected from it or acutely aware of what aspects of it you are unclear of and struggle to recall. At this point, you can actively focus on addressing those weak links in your understanding and recall of the concept (e.g., I found that I would sometimes have difficulty consistently remembering which thing something paired with, so I actively created my own mnemonics for topics where I saw those recall issues arose).

Note: there is an immense amount of complexity to this point (which gradually reveals itself as you pay more and more attention to how your mind integrates information).

•Similarly, being cognizant of what is going on in your body is extremely important. For example, many find that if they maintain some sort of connection to their body as they study (e.g., through a relaxed breathing exercise), their cognitive stamina and ability to retain information increases.

•Likewise, if your brain or your nervous system becomes overloaded, you will retain significantly more if you take a break (e.g., move around, exercise, do yoga, or take a nap) than you will if you just keep studying. Sadly, many students when they are overloaded, instead use medications like Adderal to keep going, which beyond being harmful to the brain, are less effective than simply giving the brain the breaks it needs.

Note: we have come to believe one of the reasons doctors are so resistant to learning new information is because the medical education system overloads their nervous system and hence impairs their capacity to learn new information. As such, I found that those who are the most open minded to new ideas, were typically those who found a way to avoid that cognitive burnout during their medical training.

•What you eat can significantly affect your ability to have a clear mind and study in an effective manner. In turn, a constant source of frustration for me has been finding medical students will typically eat lots of junk food while cramming for an exam, as this makes their studying process far less efficient. Likewise, healthy eating makes students much more able to effectively recall information when they are being tested on it for exams. As a learner, it is extremely important to assess if the foods you eat make your cognition clearer or if they dampen it (which sadly is the case for many of the addictive processed foods).

Note: inflammatory diets have been associated with cognitive decline and dementia, while anti-inflammatory diets have been show to prevent it.

•The specific position you study in can make a significant impact on how you learn. For instance, the default position most people study in is sitting up. Still, beyond putting significant strain on the body, it can gradually tighten the muscles in the neck, creating both headaches and fluid congestion from the brain (which often sneak up on a student as they aren’t cognizant of their body and hence do not pick up on the early signs of strain before they turn into something more severe that prevents studying). While opinions vary (as everyone is different), I believe the two best positions to study in are either squatting, or standing (especially if you can do so at a treadmill desk).

The key theme behind each of these points is that if you make the effort to actively engage in the studying process (rather than just passively trying to absorb the information being fed to you) and really question exactly what works and what does not work for you, you will be able to retain much more when you study (and have it be a much more enjoyable process).

Additionally, if you can figure out how to do this early in your academic career, it will pay dividends for a long time. For example, in addition to getting better grades, you will often be able to remember the information far into the future, whereas in contrast, I noticed many of my peers (who studied to pass tests rather than to create long term information retention) no longer recall many of the basic science concepts we learned at the start of medical school.

Note: many of the rules here also apply to general health, as since the guidelines we are fed are often so corrupt they cannot be trusted, obtaining health instead requires you to be conscious of what is going on within your own body and to then continually evaluate how each input you are exposed to improves or worsens it.

Fluid Circulation

In this publication, I have made the case that impaired circulation is a root cause of chronic illness (e.g., one of the most common mechanisms of harm from vaccines is that they cause microstrokes which are easily detectable with the appropriate neurological examination). While the harm from poor circulation can be overt (e.g., significant swelling and skin changes in the legs), typically it is subtle and goes unrecognized.

For example, a significant contributor to dementia is poor blood flow to the brain and poor lymphatic drainage from the brain—best demonstrated by how frequently the COVID-19 vaccines cause cognitive impairment or accelerated dementia. In turn, we’ve found some of the most effective treatments for cognitive impairment or dementia are simply to safeguard the brain’s blood flow (e.g., by restoring the physiologic zeta potential).

Similarly, impaired fluid circulation is extremely detrimental to mental health (e.g., one survey found the COVID vaccines caused 26.4% of recipients with a pre-existing anxiety or depression disorder to experience an exacerbation of the disorder). Likewise, physical activity (one of the most effective ways to move fluids within the body) has also been shown to be 50% more effective than medications or cognitive behavioral therapy for reducing mild-to-moderate symptoms of depression, psychological stress, and anxiety.

Note: fluid congestion in the head is often accompanied by cloudy thinking or an inability to continuously stay focused.

Because of this, being able to be aware of when fluid congestion is happening (particularly in the head) and then doing something to address that stagnation (e.g., taking a break, moving around, changing your studying position, exercising, taking a hot bath) is immensely helpful for supporting learning (and avoiding burnout).

Note: DMSO is quite helpful for improving fluid circulation in the brain, and research has shown that it counteracts both the adverse effects of strokes and prevents cognitive decline (discussed here). While we typically use intravenous DMSO to protect cognitive function later in life, it can also be very helpful after periods of prolonged mental exertion (e.g., for medical students or after you have to spend too much time writing) as it both restores depleted cognitive function and prevents long term cognitive impairment that can result from overstraining the central nervous system.

Sleep

Many studies (which I compiled here) have shown that sleep is critically important for both brain health and the long term retention of memory. This should make sense as we’ve all had days of waking up with insufficient sleep, and our minds were much less clear.

Sadly despite sleep being critically important for learning (and many other critical things like preventing dementia), very little focus is given to it in the educational process. As a result, few students know that drinking alcohol (or taking a sleeping pill) is highly disruptive to restorative sleep, and as a result, students across America, to relax from the stress of studying academically impair themselves by engaging in those activities. Likewise, basic practices of sleep hygiene (e.g., getting to bed at a regular hour, avoiding coffee later in the day, or not being exposed to blue light from screens at night) are almost never mentioned to them.

Disregarding the importance of sleep is particularly tragic for doctors in training, as during their medical residencies, they are often forced to work 24-30 hour shifts, under the belief they “need more time to be trained sufficiently” despite the fact sleep deprivation impairs learning and significantly increases (sometimes fatal) medical errors.

Note: a more detailed summary of the critical importance of restorative sleep and the simple approaches that can be taken to improve it can be found here.

Whole Body Health

One of the major issues with how medicine is practiced today is that each issue is seen as an isolated problem which requires its own pill to treat, when in reality, many ailments are simply different manifestations of how the same underlying issue expresses itself wherever the patient is the most susceptible (e.g., consider how many different side effects have been seen from the COVID vaccines or that those side effects frequently arise at sites of pre-existing weaknesses in that individual).

Likewise, many of the same degenerative processes we see at the end of life simply represent the same underlying diseases (e.g., fluid congestion) in the body worsening with age. For instance, as I’ve tried to show here, beyond a clear mind being valuable for memorization and academic success, the habits that create it are also what stave off cognitive impairment, and eventually dementia—conditions which despite decades of research (that trillions have been spent on) conventional medicine still cannot offer a solution to.

Similarly, the core degenerative processes we face can often collectively compound into the critical illnesses our society still struggles with. For example, many psychiatric illnesses (which under our paradigm can only be “treated” with perpetual psychiatric medication) result from neurological damage, and as such, can often be addressed by addressing the degenerative processes that create neurologic damage.

For example, as I showed here, the same degenerative processes (e.g., poor sleep or poor circulation) can cause similar psychiatric issues, and likewise, the same treatments that improve either also improve mental health (e.g., previously I showed how DMSO and how ultraviolet blood irradiation both improve circulation, decrease inflammation, and improve a variety of psychiatric illnesses).

Note: all of this is also quite important to academic success, as frequently the most significant challenge students face is mental fogginess or anxiety while taking tests—but sadly few options are presented for them besides anti-anxiety medications to take at those times.

It is my sincere hope this information was able to provide a few useful tools for studying and highlight just how interconnected many aspects of wellness are.

In the final part of this article, I will discuss a few of the specific strategies, supplements, and foods we found were the most helpful for us retaining information and effectively performing on tests throughout our academic careers—including one approach that has the remarkable side effect of creating lucid dreams.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Forgotten Side of Medicine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.