How Medicine Takes Away Innovative Doctors

Exploring a few of the ways the system uses financial incentives to maintain its own stability

Recently, I published an article about how common (but not dangerous) skin cancers caused by sunlight exposure were lumped together with rare and dangerous skin cancers caused by a lack of sunlight exposure, thereby creating the mythology that sunlight was extremely dangerous and frequently caused deadly skin cancers. In turn, I argued this redefinition of “skin cancer” was concocted by a marketing firm that was commissioned to turn dermatology into a lucrative specialty, and that rebranding dermatologists as skin cancer fighters was decided upon since cancer treatment is always lucrative and once you really look for “skin cancers,” you can find a lot of them.

Sadly, while this strategy enriched the dermatology profession, it had a few major issues which included:

•This rebranding required dermatology to create the perception that sunlight was a scourge we needed to be protected from. In reality, sunlight is one of the most essential nutrients for the body (e.g., for mental health or preventing cancer), and avoiding it has been shown to double one’s risk of dying (e.g., smokers who get regular sunlight do as well as non-smokers who avoid it).

Note: many of the sunscreens on the market are highly toxic, while the natural ways to improve skin sunlight tolerance (e.g., dietary changes) remain virtually unknown.

•While the diagnosis of skin cancer has risen dramatically, its death rate has remained relatively unchanged. Likewise, a variety of simple, safe, and proven effective treatments exist for skin cancer that have never seen the light of day because the dermatology profession has a strong financial incentive to prevent them from ever being adopted (much in the same way they are incentivized to avoid natural solutions to sunburn).

•Because of how much money is now involved in skin cancer, it’s drawn a lot of unscrupulous parties into the business. This includes doctors who conduct all sorts of unjustifiable (and painful) procedures on Alzheimer’s patients near the end of their lives and private equity firms buying up dermatology practices that are geared towards doing as many of these procedures as possible and (to save costs) are staffed with mid-level practitioners (e.g., nurse practioners) who often make mistakes a fully trained dermatologist would never do.

•Many of the lucrative procedures done for skin cancer have side effects. For example, I’ve met numerous patients who have had significant long term problems at the excision site of their skin cancer..

Because of how many people have been affected by this scam, it struck a cord and quickly went viral (e.g., one tweet about it has received almost 3 million views). Likewise, I discovered a few well-known people had gone through exactly what it described. Consider for example this segment Jimmy Dore did about the article:

After I published the article I received a lot of feedback from my colleagues. While they generally agreed with it, they informed me that I needed to address three points:

•First, while Basal Cell Carcinomas (the common skin cancer linked to sunlight) do not metastasize and thus are never fatal if left unaddressed, over years, they can grow to become quite large (which is a scenario dermatologists periodically encounter in clinical practice). While some people choose to never do anything (and still live) most people, understandably will want that large external tumor removed. Unfortunately, if the tumor is massive at the time of its surgical removal, it is almost guaranteed to lead to “poor cosmetic outcomes” (e.g., nasty scars) since a large portion of skin has to be removed for the excision. For this reason, while BCCs are not something to be afraid of, it is important to be aware that they can continue to slowly grow for a long time, and hence they are better removed sooner rather than later.

Note: in that article, I cited a few case studies of my favorite skin cancer treatment providing a satisfactory resolution for large BCCs that would be difficult to surgically remove and achieve a good cosmetic outcome.

•Second, since the COVID vaccines came out, my colleagues have seen a small number of cases of BCCs metastasizing in their patients—something they had never seen over the decades they had been in practice prior to the COVID vaccines coming out. As there is so little data on this, I can’t say how much of a risk exists for basal cell “turbo cancers” but I need to be clear that it’s more than zero for the vaccinated.

•Third, they felt that diverting the brightest minds in medicine into dermatology (because it is a high-paying and low-stress specialty) was a critical area to focus on.

Psychological Demographics

While people in society tend to behave in similar ways (e.g., propaganda “works” because it appeals to something present within the majority of the population), there are still significantly different demographics within each society that won’t comply with the same things.

Self-Directed Individuals

For example, within marketing, it is known that the majority of consumers make their purchasing decisions on the basis of being repeatedly told to do so, while the minority of consumers will buy things on the basis if it actually makes sense to buy the product. Since self-directed consumers represent a minority of the population, marketing hence typically caters to non-self-directed consumers (e.g., consider how many advertisements for consumer brands you see everywhere around us).

Note: I was told an Ivy League institution studied this question and found that around 10% of America’s population were “self-directed” consumers. While this matches what I’ve observed in the world, and I assume there is a 90/10 split in the population, I do not know if that assumption is actually correct because I was never able to find the study.

Likewise, one of the lessons many have gotten from COVID-19 is that most people make their decisions on the basis of what their peers or the crowd around them are doing (which is known as the social proof heuristic) while a much smaller number will see things for what they are and go against the crowd to do what they think is correct. Throughout my life I’ve sought out these self-directed individuals as friends and colleagues, and throughout COVID, I noticed many of the prominent dissidents (e.g., those I now know personally) defied the narrative because they were in that minority of the population who were “self-directed.”

In turn, when writing this publication, I’ve deliberately targeted it towards the self-directed segment of the population—something which has limited the reach of my readership (as I have avoided doing a lot of things you are “supposed to do” to get traffic) but has made this publication much more satisfying for me to write (as without personally valuing what I am doing here, I would not have been able to motivate myself to put the time I do into it).

Alphas to Epsilons

One of the most famous dystopian novels was Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. One of the many themes it posited was that different members of the population had an innate degree of talent and certain roles they were content being in, so if someone was placed in a role that did not “satisfy” them, they would create social instability by trying to create a new place for themselves.

For this reason, that fictional society encouraged a rigid caste system where people were categorized into one of five casts and then given a role to fill in society that matched the innate drive and capacity of their caste. Specifically, alphas (the rarest) were intellectuals who produced media content for the rest of society, betas (the second rarest) managed complex scientific processes the society relied upon, gammas did everyday jobs, deltas did manual labor or factory jobs, and epsilons did all the jobs no one else would be willing to do. This was done under the theory it would lead to maximum social happiness and cohesion, but when looked at from the outside, the society seemed quite grotesque.

Nonetheless, many people I’ve spoken to believe that the current social controllers have essentially sought to create a similar caste system where individuals could be segregated by their “talent” and then assigned to the roles appropriate for them (e.g., the “smartest” of each generation go to the best colleges where they, in turn, are given a pass to enter the establishment—a process which conveniently favors the upper class since those institutions tend to be biased for admitting children from that upper class).

Note: frequently when I see how people are slotted into their roles in this society I marvel at how closely it matches the system described within Brave New World (e.g., there are many “betas” who are locked into high paying science-related positions that have very narrow parameters over what they are actually allowed to do). This in turn often leads me to wonder if Brave New World was a blueprint for the social controllers, especially given how widely promoted the book was (e.g., it’s often required reading within the public school system).

Killdozers

One of the struggles society has always faced is that a certain minority of the populace is psychotic or psychopathic, and when given the opportunity will lash out and hurt others, especially if they feel they have been wronged.

For example, Marvin Heemeyer, was a resident of Granby, Colorado who ran into trouble after he bought a piece of land that had sewage disposal issues, and in turn, became increasingly disgruntled as no one would agree to any of the proposals he put forward to address the costly situation. In time, this morphed into a vendetta against those he felt had wronged him—which ultimately included a lot of people. From reading the accounts of the event, it really seems as though everyone tried to work with Heemeyer to find a reasonable solution to the issues, but this was to no avail as his mind became so anchored to the fact he had been wronged by a vast conspiracy that he selectively filtered his perception of reality to gradually create a larger and larger story of how he was the victim of a grave injustice.

As Heemeyer’s original goal had been to open an automotive repair shop on the land, he eventually opened a muffler repair shop which he then closed in 2002 selling his property for a large profit. Believing god had chosen him for a mission, he then purchased a bulldozer from California and spent the next two years using his resources to gradually cover the bulldozer with homemade armor plating. Two years later, he emerged from his muffler shop with this killer bulldozer and began systematically demolishing the buildings of everyone whom he felt had wronged him, ultimately causing 7 million dollars of property damage (11 million in today’s dollars).

Note: a full video of the incident can be viewed here.

This incident became immortalized on the internet because everyone was essentially helpless to stop the “Killdozer” (rather it only stopped when it got trapped by a basement collapsing under it) and because no one died—something which led many to believe Heemeyer was a lone man fighting for justice against a corrupt system who simultaneously tried to avoid any loss of life during his vendetta (although it’s quite possible no one dying was simply due to luck).

Note: at the time this was happening, the Governor of Colorado allegedly considered calling in a missile strike to stop it, but avoided doing so because the collateral damage that would result was likely to exceed what the bulldozer had inflicted on the town.

Based on those events, I believe Heemeyer was a frustrated and mentally imbalanced individual—something which is never a good combination, but he wasn’t evil or sociopathic (instead he had some degree of a desire to do the right thing coupled with psychosis and delusions of grandeur).

Note: I specifically highlighted this story because the Wikipedia account paints a vivid picture of what this mental imbalance looks like.

If you then consider that many other frustrated and mentally imbalanced people also exist, some of whom are also violent or sociopathic, you begin to develop an appreciation for how much of a challenge it is to prevent a subset of those mentally imbalanced individuals from causing too much damage to society.

Note: in a recent article discussing the link between vaccination and violent crime (due to the known complications of encephalitis), I highlighted that many of these dangerous psychopaths (e.g., infamous serial killers) appear to have emerged after the (now-banned) DTwP vaccine was introduced. This vaccine was notorious for frequently causing encephalitis, and was eventually phased out in the late 1980s and replaced with the less brain-damaging DTaP vaccine (although DTwP is still given to many of the poorer regions of the world).

My general understanding of the subject (as I heard this all through word of mouth) is that one of the “solutions” that was devised to address this problem was to create an economy where everyone had to be constantly working, as in those circumstances, it’s hard to find the time to spend two years in one’s garage building a Killdozer. Likewise, because most jobs that exist require one to be actively interacting with others, if for some reason you still found the time to build a Killdozer, many of the people you interacted with would notice something was off and eventually would do something about it.

In turn, (per my understanding) this created the realization that even though increasingly sophisticated technology was eliminating the need for much of the labor society had previously relied upon for its survival (e.g., mass-monoculture farming requires a fraction of the physical labor previous approaches did), that elimination of labor was not deemed to be good for society. Because of this, a variety of pointless jobs emerged which essentially were created to ensure people would constantly be needing to work and hence could not have the time to act up.

Note: similarly, if people are struggling to make ends meet, they are often much less likely to protest the current government, which is likely also a motivating factor for keeping them working from paycheck to paycheck.

Suppressing Consciousness

I shared each of the previous examples to illustrate that the social planners put a lot of thought into ensuring society would continue to function in a smooth and stable manner. While it’s often great that the planners do this (e.g., we take for granted that there is always running water and electricity), once individual human behaviors are “managed” it requires creating manipulative institutions that focus on the collective good rather than what is fair and just for each member of the society.

For example, as we all saw throughout COVID-19, the central planners are always quite willing to push mass vaccination campaigns upon society that support the “greater good” even if they know sacrifices have to be made. In turn, once it became clear they messed up, they doubled down on their lies rather than admit fault.

Note: I recently dissected the New York Times’ disingenuous apology to some of those injured by the COVID vaccines to illustrate that duplicity.

In turn, one of the largest challenges each system always faces is the awake people who see through its propaganda and don’t wish to comply with it. So in addition to them just having no time for anything besides “work,” I see a variety of other strategies being repeatedly utilized to address this “problem.” Some of these include:

1. In this month’s open thread, I discussed the collective gaslighting societies engage in which seeks to convince each awake person they are crazy and that no one else sees what they are seeing. Because of this, the awake don’t share what they are perceiving (due to the fear of the retaliation they will face for doing so) and likewise are continually tortured by how psychologically isolated they are.

Note: In my own life, I felt incredibly fortunate to have crossed paths with numerous awake people at a young age (who likewise felt the same way), and even more fortunately, I met enough of them earlier on that I discovered how to quickly identify them within a crowd (discussed further in the last part of this article). Because of this, one of my goals with this publication (and hence why I avoid marketing approaches that cater to non-self-directed individuals) has been to create a vehicle that can help awake readers here forge the same connections I was so blessed to have.

2. In addition to peer pressure awake individuals experience to silence themselves and reject what they are seeing, a variety of other tactics are also used to directly impair their perceptual capacity. For example, when people eat junk food, their capacity for clear thought is diminished (which is why it always astounded me that medical students typically eat junk food when cramming for exams). Likewise, while it’s more subtle, I do believe certain electromagnetic fields impair one’s clarity of thought and similarly, all the artificial disruptions we have to the natural sleep cycle (e.g., artificial blue light) have significant adverse cognitive effects on those who are exposed to them.

However, the neurotoxic effects of pharmaceuticals are much more overt (e.g., I’ve lost count of how many people develop cognitive impairment after starting a completely unnecessary statin or antidepressant).

Note: part of the reason why I wrote the antidepressant series was that it helped paint a picture of what it’s like to lose one’s mind and have no idea what to do while it’s happening—something many people I know have gone through because of a neurotoxic pharmaceutical.

3. Likewise, I’ve seen many heartbreaking cases of perceptual blunting following the more toxic vaccines (e.g., persistent brain fog is one of the most common side effects of the COVID vaccines and likewise we’ve seen cases of many older individuals developing dementia shortly after these injections). Similarly, I and many of my colleagues have long believed (due to the effects of post-vaccine encephalitis) that to varying degrees this consistently follows vaccination as we find stark differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated children.

Note: in that previous article I provided the data to substantiate these observations.

Furthermore, since subtle physical changes can often be observed once this ‘blunting’ happens, we gradually learned to identify it. Over time, I learned that almost all of my awake colleagues were noticing the exact same characteristic signs. In turn, after I described it, many of the readers here had the sobering realization they too had seen it (as they had an inkling it was there but couldn’t quite put it into words).

I mention all of this because one of the most reliable signs I’ve found for identifying awake individuals is the absence of this blunting (which can be visually observed). I’ve hence long suspected that routine vaccines to some degree “blunts” one’s ability to perceive what’s in front of them, or to interact with the world while remaining connected to their heart (a position Rudolph Steiner also held).

Note: connecting to the awareness within one’s heart is one of the most reliable ways to avoid being led astray.

Escape Valves

While each of the previous approaches is somewhat effective at maintaining social order, large numbers of intelligent and perceptive people who can disrupt the existing power structure always is a threat. In turn, society finds ways to ensnare them so that they never challenge the system.

For example, to some degree, our society is a meritocracy where the most talented and capable people rise to the top (e.g., getting the highest paying jobs). Because of this, much of our society works very hard to succeed within academia (e.g., earning the elusive degree from an Ivy League institution) and everyone who is “smart” is always told from a young age they need to go to the best college.

This paradigm thus makes it possible to catch most of the “intelligent” individuals, and focus society’s resources onto them so they can be trained into being compliant and hence not threaten the system (e.g., a significant portion of a doctor’s medical training is essentially a conditioning process that ensures they will never step out of line). Likewise, once they finish that education, they are often so laden with student debt that they feel they have no choice except to continue to comply with the system.

Simultaneously, there is still a certain portion of people that everything mentioned thus far doesn’t work on them. For these folks, the system instead takes a clever approach—our institutions offer high paying and low stress jobs (e.g., being a dermatologist) that are dangled as carrots to the highest performers (e.g., those who aren’t dulled by all the insults society throws at our minds). In turn, once they reach those elusive positions, they are required to stay in their lane in order to retain their comfortable lifestyle and hence will never disrupt the system.

As stated earlier, a few colleagues reached out to me about my mentioning that an immensely talented and good-spirited colleague chose to go into dermatology solely because of a desire for the salary and lifestyle that specialty provided. In that discussion, they proposed that the position in medicine dermatology promises, is essentially an “escape valve” for the system to alleviate the pressure that would emerge from highly talented and independent minded people filling our institutions and then disrupting them.

More importantly, this situation is not unique to medicine. Many other industries (e.g., tech) have very talented people who the system filters for and then locks into high paying jobs where they are kept out of sight and out of mind. In short, my colleague’s example helps to explain why so many highly talented people who could make things better have been so effectively hidden away.

Empowering Beliefs

Many people do not appreciate how much of their happiness and satisfaction in life (e.g., their emotional health) is the product of the beliefs they choose to carry, or the ones that society gave to them which they never chose to question.

For example, a good case can be made that many of the problems in our culture stem from the fact too many people do not believe in the spirit or that anything follows death. Because of this, they think this life is the only one to live and they focus on trying to get everything they can get in this one chance they have—even if it is immensely destructive to the world around them. This in turn is incredibly short-sighted as that path rarely gives happiness, and more importantly, typically leads to immense repercussions for their soul later on.

Note: exactly what happens after death has largely been a subject of faith for those who have not had direct experiences with it. Fortunately, a body of scientific research is gradually emerging that shows there is something very real that happens once the body is no longer alive (some of which I compiled in this article).

When I was a child, I had three very important experiences which imprinted a very different set of beliefs into me.

•First, I noticed I would constantly want things (e.g., toys that were marketed to me), but once I had them, I quickly lost interest in them. In time, this evolved to me frequently feeling ripped off that I’d spent money on something I bought, and hence, I became quite judicious about what I purchased. That trait has remained with me to this day, and I tend to live a minimalistic lifestyle where I shy away from unnecessary spending.

•Second, I lost track of how many people I’d met who had a lot of money but just were completely miserable and conversely, how many people I met with almost nothing who had a deep level of happiness many would give almost anything for. This made me recognize that the consumerist fable society sold us (that your happiness and purpose came from how successful you were and what you then bought) was a lie, and if I allowed myself to get pulled into it, money would effectively become a dangerous drug I would crave more and more of, but at the same time become more miserable as I consumed more and more of it.

•Third, from a young age, I was involved with various (legitimate) charities that raised money to help people in poorer countries who were in very dire straights. From being involved in them, I was always struck by the fact that what was an inconsequential purchase for me could equate to the difference between life and death for someone in a less fortunate part of the world. Because of this (and likely my previous emotional reluctance to avoid frivolous spending), I accepted that while I could never solve all the world’s problems, I was ethically obligated to spend the money I had in a judicious manner.

Over the years, exactly how I’ve navigated these points has changed (e.g., I’ve become less frugal once I came to realize certain decisions I made were costing me more than I appeared to be saving—due to lost time or not taking advantage of opportunities the universe had presented to me) but my general ethos has remained the same. In my eyes, I was incredibly fortunate to be born in the part of the world where I didn’t have to suffer the extreme poverty, violence, and political repression many face, so my goal was to hence reinvest my “good karma” into creating more of it rather than squandering it on things I didn’t need.

Note: this process also led to me developing my own set of “empowering beliefs” (since the ones the society offered—while good for maintaining general social stability, rarely gave real purpose or personal development to those who ascribed to them). Because of this, I put a lot of thought into what beliefs I actually wanted to have my life revolve around. For example, I’ve long viewed life as an opportunity for learning and hence prioritized trying to determine what truths actually underlie the world we inhabit (regardless of how uncomfortable they are). Similarly, I’ve long sought out difficult patients who are quite challenging for me to treat as I learn a great deal from working with each of them.

Navigating Unjust Institutions

Over time, I discovered one of the things I most deeply valued was my own personal freedom and having the liberty to fully engage with the spontaneity life threw at me. Unfortunately, many of the institutions our society creates to ensure social stability and cohesion stand in direct opposition to this, and hence, one of my struggles was finding a way to survive within these institutions while staying true to myself.

This was understandably challenging, but in time, I found a few things that made it much more manageable. These included:

•I’ve come to accept that regardless of what you try to do, life often just isn’t fair (e.g., consider what it’s like for the people who are born in the less fortunate parts of the world). Because of this, I never expect things to be perfect, and instead, when confronted with difficult situations, I simply ask myself if it’s possible to make what’s already there better.

•I would often find holes in the institution I could fit into (e.g., certain parts of it weren’t well understood so I was given a lot of autonomy to work within them or I found awake administrators who felt trapped by what they were forced to do and hence wanted to what they could to covertly support other awake people within the institution).

•I made a point to only voluntarily sign up for something I did not want to do (e.g., arduous training) or that which went against my own values (e.g., parts of what I knew I needed to do on the road to becoming a doctor), if I felt that unpleasant choice would lead to something that was worth this temporary conflict with my own free-will.

Note: many people who go into medicine are initially idealistic about what they aim to become once they are doctors, but most of them then gradually become beaten down by the system and eventually habituate themselves to a role they are unhappy with but rationalize the necessity of (e.g., I’ve lost count of how many doctors I know who cited their student loans as they reason they stayed with their unpleasant corporate job). Hence I always tell medical students to never lose sight of why they became a doctor in the hopes at least a few of them will take that to heart during the course of their careers and pick a specialty that provides genuine meaning to them.

•I made a point to take personal responsibility for my decisions (e.g., by being clear with myself that it was my choice I was allowing myself to be subject to the unfair dictates of an inflexible institution). This, in turn, made it possible for me to avoid being internally conflicted over my actions and prevented me from shredding inside as I engaged with an unjust and restrictive institution (which I think is critically important for avoiding burnout—one of the largest problems facing physicians). Conversely, it also gave me the ability to have the clarity to recognize whenever a useable window had presented itself for me to act and do what I felt was right (rather than attacking the system as a response to my own internal conflicts over what was happening).

•I made a firm commitment to myself that I would only allow myself to be within these situations for as long as I had to and not a moment longer. For example, I made one of those commitments before applying to medical school, chose a specialty I felt would allow me to uphold this commitment, and after I completed my medical residency, I avoided taking a higher paying job that I knew would trap me within a toxic environment, and likewise, I made sure the positions I took would serve as platforms towards allowing me to follow the path my heart had always yearned for.

Note: many other strategies also exist. I primarily shared these ones because I felt they were the most likely to be applicable to what each of you may encounter.

Financial Enslavement

A phrase that always stuck with me was “don’t sell your soul to the eye on the back of the dollar bill.”

Sadly, much of our society revolves around doing this. For example, in a previous article, I discussed how the ruling class made a decision to economically impoverish the society so that they would have no choice except to submit to whatever a corporation forced them to do—such as a mandating an unsafe and ineffective vaccine. In that article, I emphasized that the economic model of control was so appealing to the ruling class because of how effortless it made enacting policies be, as a central policy which gave more or less money for something would immediately result in people behaving differently. In contrast, previously to change the behaviors of society, it typically required the state army to force the population to comply and a significant amount of propaganda, both resources intensive processes which could hence not be repeatedly deployed for each agenda.

As my focus has always been on doing whatever I can to maximize my own free will and autonomy, it became quite disturbing to witness repeatedly how a financial incentive could easily hijack someone else’s free will and cause them to do whatever a puppet master wished for.

In turn, within medicine, I see many different examples of this. On one hand, we have the reality of the corporatization of medicine, where many doctors are forced to do whatever their corporate managers insist they should (e.g., treating COVID patients with remdesivir rather than ivermectin or hydroxychloroquine or pressure patients to take an experimental vaccine the doctor had serious doubts about).

Likewise, we frequently see doctors be subtly or overtly manipulated by the pharmaceutical industry through small and large financial incentives. For example, pharmaceutical sales reps will constantly give small gifts (e.g., free meals) to doctors in order to incentivize them to sell their drugs (which works), and likewise will often give medium size gifts (e.g., a tropical vacation) because those yield an even greater return on the investment. Worse still, we currently have an epidemic of paid off “experts” who continually promote their sponsor’s interest (e.g., by signing off on fraudulent research or voting for medical practice guidelines that require using their sponsor’s products) and rather than be called out for this are continually elevated to the most prestigious positions society can offer.

Conclusion

When my friend made it into dermatology, I told them that while it was a remarkable achievement (as dermatology is one of the most competitive medical specialties) I felt that in the long term they were making a mistake. This was because I knew how intelligent and innovative my friend was, and I felt that if they got dragged into the rote routine of a dermatology practice (lots of skin exams to identify the profitable cancers to remove) that repetitiveness would gradually drive them crazy. More importantly, my fear was that this choice would prevent them from being able to cultivate the remarkable talents they had been born with and use them to make a mark upon the world—which in turn would lead to them having a deep dissatisfaction with life no amount of money could make up for.

As best as I can tell, my words made a mark on my friend and motivated them to pursue a variety of important innovations within their medical specialty.

However, this is typically not what happens. Instead, much of the talent our society has to offer is sequestered within high paying positions that have very specific (non-disruptive) things they want those individuals to do (e.g., Google figuring out better ways to monopolize the attention of their audience and hence sell them even more advertisements).

Because of this, medicine is experiencing a crisis of innovation. Many of society's most talented members are content to simply take the easy and lucrative positions offered to them, while others who cannot accept this status quo venture outside our institutions and create their own innovations within the great laboratory of private clinical practice.

Unfortunately, while there was a steady interplay between these two in the past, it’s become much rarer now, and as a result, fewer and fewer innovations from private practice are able to enter the public sphere. This I believe is due to the monopolization of healthcare (e.g., an ever-expanding list of government regulations makes it very difficult to practice outside of a healthcare corporation) and that there is an ever expanding deification of “credible sources” (e.g., studies published by the elite institutions).

As a result, we’ve seen a dramatic decline in innovative ideas that overturn the existing dogmas (e.g., consider how paradigm shifting the discovery of DNA was) emerging from the scientific establishment, and likewise any independently produced innovation tends to be shunned and attacked by the medical system (e.g., consider just how many different COVID-19 treatments were suppressed over the last few years). This I believe is reflective of the gradual institutional decline that has happened throughout our scientific apparatus as a result of science and medicine “proving” themselves to the world, after which, they began receiving large amounts of money for more research without ever having to be accountable for the value of that research—which naturally encourages mediocre work which conforms to the pre-existing societal biases rather than risky work that challenges the existing orthodoxies and moves science forward.

Note: as I discussed in a previous article, the primary cause of this loss of innovation throughout the scientific field is us having a grant system that punishes scientists who conduct unorthodox research and instead only incentivizes propping-up and refining existing paradigms. Since grants are the economic lifeblood of most professional scientists, they cannot risk being cut off from it, which once again shows how easy it is to use money to buy someone’s silence and compliance.

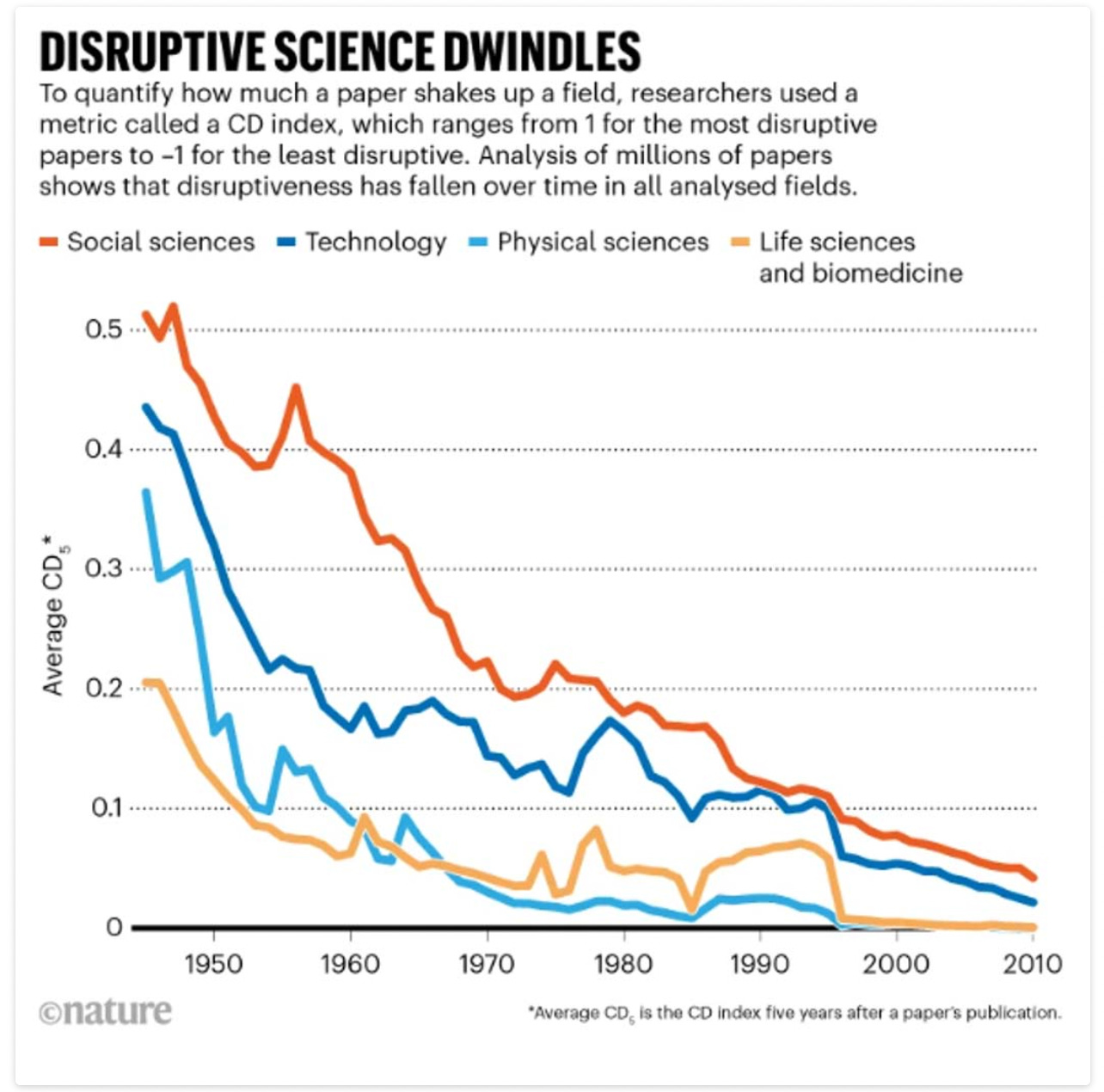

One of the best proofs of the argument made by Kendrick can be found in this study published by Nature:

Note: conversely, the amount of money we’ve spent on scientific research has steadily increased during this time period.

In essence, I believe we’ve reached the point where we are no longer getting a good return on the investment being made in many of our scientific institutions. As more money is spent to address the scientific deficiencies we face (e.g., an effective way to respond to COVID-19 or a solution for Alzheimer’s disease), our return on investment further worsens.

Note: I cited these two examples because (like many other examples) they represent extremely costly challenges to society billions are spent on each year for research and poor treatments approaches that already have affordable, safe and effective solutions which have been developed for them. Unfortunately, the medical industrial complex refuses to look into those since so much money is made from the current dysfunctional paradigm with the disease, in essence demonstrating why spending more money to “solve” them is actually counterproductive..

My overall hope is that the COVID-19 crisis will reset the playing field. With trust in medical and scientific professions diminished because of their abysmal COVID-19 response, they can no longer rely solely on their historical prestige. Instead, my hope is that a pressure will be put on them to produce real results the public can recognize has value and hence reestablish the innovation science so desperately needs and which its initial credibility was built upon.

To learn how other readers have benefitted from this publication and the community it has created, their feedback can be viewed here. Additionally, an index of all the articles published in the Forgotten Side of Medicine can be viewed here.

Great summary on the systemic failures of medicine. As a trained general and vascular surgeon in the 1980s, I always felt the regimented process was to create self discipline and introspection in one’s avocation. I was taught and trained that there is many ways to “skin a cat” as long as a satisfying outcome resulted for the patient. There was mostly critical thinking involved in the lengthy , rigorous education between residents and staff. However , there were a few staff professors who took the “my way or the highway” approach. Unfortunately, that approach has become the rule not the exception as Big Pharma and Big Medical Device Technology drives the financial incentives in every hospital and academic training program. Along with this outcome is the perverse federal government incentives from HHS with DEI and woke thought resulting in a Pavlovian response from medical professors, students, hospital administrators, and clinical researchers. I don’t recognize my field of vascular surgery. The specialty journals are filled with nothing but feel good, DEI garbage editorials along with full page ads from the latest medical device technology. And eight years post retirement, I chuckle that the latest clinical studies , laced with poor statistical analysis, are vascular surgical issues debated back to the beginning of the millennium. While the progress in device technology is truly mind boggling , 80% don’t improve long term outcomes mortality or the ever important quality of life. Depending on one’s specialty what is axiomatic these days 1)” if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail” 2) “it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his income depended on his not understanding it” - Upton Sinclair.

After I posted this article, I realized I forgot one of the most classic examples of financial incentives in medicine. Doctors who vaccinate are both paid to vaccinate, and given a significant bonus based off the percentage of people they vaccinate. Because of both, especially the latter, many are highly incentivized to ensure all the patients in their practice vaccinate.